This is the transcript for Book Two, episode 5 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: Triumvirate (2). This story is about Ali Akbar Davar, the architect of Iran’s modern judiciary and the end of the alliance that put Reza Shah in power.

Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

Firuz Nosrat al-Dowleh was a Qajar prince, a former governor of Fars, and a seasoned statesman. He had held key positions in multiple governments: Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Finance, and Minister of Justice.

His fingerprints could be found on nearly every major initiative of the era, from the oil negotiations to the construction of the Trans-Iranian Railway.

But now, Firuz was barred from holding any public office in the country.

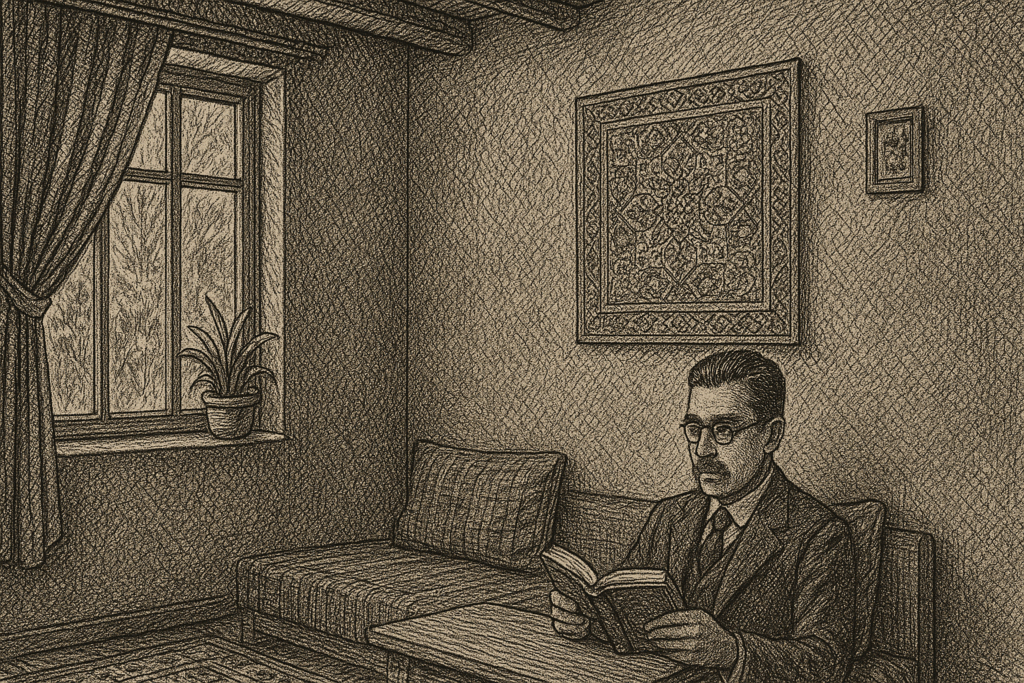

He spent his days in quiet isolation.

Surrounded by family and children, he tended to his garden and managed his many properties across Iran through proxies.

Though he had spent most of his life in Tehran, Firuz was now living in Semnan. A modest city on the southern slopes of the Alborz Mountains, north of the capital.

At first, he was bitter.

He blamed his allies, held grudges against the court, and viewed Reza Shah’s actions as unreasonable paranoia. But over time, he began to appreciate the stillness.

A break from the chaos of Iranian politics wasn’t the worst fate imaginable.

Yes, soldiers watched him from afar, monitoring his every move … but he was alive.

And after hearing of Teymourtash’s murder, that counted for something.

Firuz Nosrat al-Dowleh: A Quiet Life After Politics

In April 1937, Firuz began his day like any other.

He visited the local market to buy bread and groceries. He returned home, fed his dog—his only real guard these days—turned on the radio and sat down for breakfast.

Then, as usual, he turned to his books.

Reading was one of the few distractions he had left. It was the only thing that gave him peace. He’d lose himself in histories of Iran, tracing the rise and fall of dynasties, the decisions that shaped nations.

Firuz snapped out of it. He looked outside.

Three guards had broken in through the main door.

His dog, startled and barking furiously, lunged toward them—his only line of defence. But the guards didn’t flinch. One of them calmly drew his gun, took aim, and fired.

Silence.

It rang louder than the shot itself.

The End of Firuz Nosrat al-Dowleh

Firuz didn’t have time to process. He ran. Firuz went towards the hallway and into the basement. He knew the place well. There was a small recess, hidden behind stacked crates. The perfect hiding spot.

But the boots were close behind. Marching inside.

As he reached the basement stairs, the soldiers caught up. One of them shoved him hard, sending him tumbling down. He hit the floor and rolled into the corner.

The three soldiers followed, surrounding him.

The one in charge stepped forward and handed him a pen and a sheet of paper.

It was time to write his will.

Firuz took his time.

His hands were trembling. The paper was soaked with blood, sweat, and the weight of what was to come. Every word he wrote felt heavier than the last.

But he pushed through.

He was a seasoned bureaucrat. Drafting a legally sound, binding will—even at gunpoint—was something he could still manage. He even wrote a letter to his family on the back of the paper.

But time, no matter how long it feels, always runs out.

Eventually, he reached the end. And as he signed his name, the whole of his life played before his eyes.

He was a Qajar prince, a former governor of Fars, and a seasoned statesman. Firuz had held key positions in multiple governments: Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Finance, and Minister of Justice.

He had everything: lineage, education, experience.

In another world, he could’ve been prime minister.

Or maybe even king.

But what he didn’t have was the one thing that mattered most in Iranian politics:

Luck.

Later that day, the guards brought in a doctor.

After a brief examination, the doctor signed the certificate and declared the cause of death:

Heart Attack.

The Revival Party: Reforming Iran’s Politics in the 1920s

In the early 1920s, a newly founded political party was gaining momentum, expanding its influence in the Fifth Parliament. The Revival Party (Hezb e Tajadod) was formed by a generation of Western-educated elites who had grown disillusioned with Iran’s slow progress.

It was a secular, progressive movement with strong liberal and nationalist tendencies.

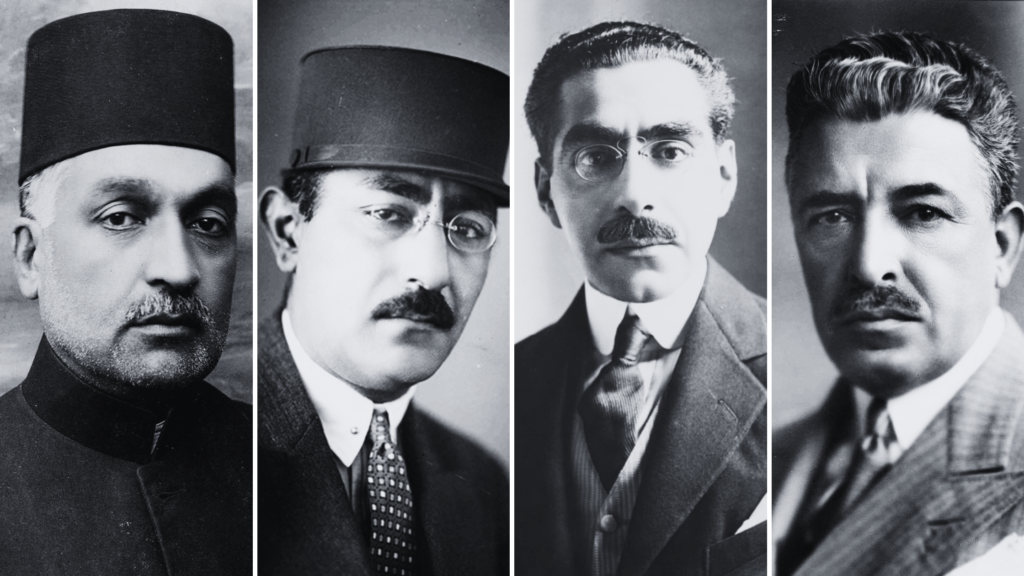

The party’s founders—Mohammad Tadayon, Abdolhossein Teymourtash, and Firouz Nosrat-ed-Dowleh—were ambitious, modern-minded politicians. But the mastermind of the party and the force behind its creation was none other than Ali Akbar Davar.

While Firouz came from Qajar blood and Teymourtash’s parents were rich and noble landowners in the east, Davar had to work for everything he had in his life.

Ali Akbar Davar: From Humble Beginnings to Judicial Reform

Ali Akbar Davar was born in 1885 to a middle-class family.

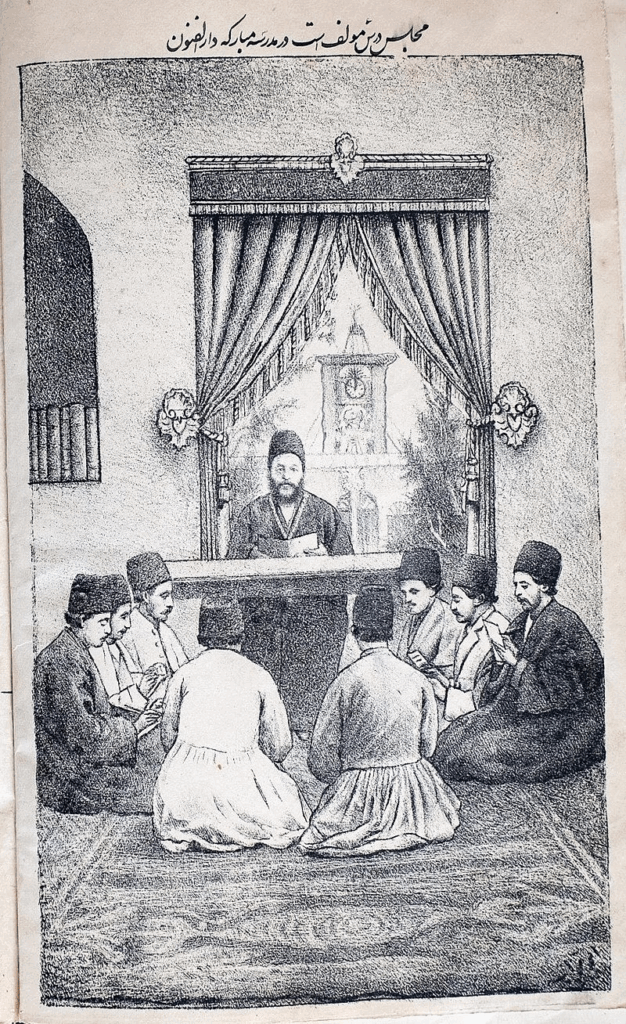

His father worked as an accountant in the Qajar estate, earning enough to give his son a solid start in life. From a young age, Davar was enrolled at Dar al-Fonoon, where he studied law.

You might recall that Dar al-Fonoon was Iran’s first modern university, established by Amir Kabir, the reformist grand vizier of Nasir al-Din Shah and the grandfather of Firuz Nosrat al-Dowleh. Modelled after Western academic institutions, it stood in sharp contrast to the traditional religious madrasas of the time.

But Davar’s ambitions outgrew Iran’s limited educational system. He made his way to Switzerland, where he earned a Doctorate in Law from Geneva.

While abroad, he remained deeply engaged in Iranian politics. He published critiques of the 1919 Anglo-Persian Agreement, and when he heard about the 1921 coup led by his friend Sayyed Zia, he knew it was time to return.

Davar left Europe and made his way back to Iran.

He saw an opening. And he took it.

But there was a problem.

How Ali Akbar Davar Built His Political Power and Influence

Unlike Teymourtash and Firuz, Davar lacked both the funds and the connections to climb the ladder of power. So he did the only thing he could—he built the ladder himself.

To be truly influential, Davar needed money—and lots of it.

So he made a calculated move. He divorced his wife and remarried—this time to the daughter of Moshir al-Dowleh, one of the most powerful grand viziers during Ahmad Shah’s reign. Moshir al-Dowleh’s family wielded immense wealth and political capital, and through this marriage, Davar secured access to both.

With the financial backing in place, he turned to the next step: influence.

Davar launched a newspaper—his own platform to speak directly to the people, to share his ideas, and to raise his profile among Iran’s middle and upper classes.

The paper was called Mard Azad—“The Free Man.”

The Iranian intelligentsia quickly made it a required reading, and people soon saw Davar as a modern, reformist thinker pushing for change in a stagnant system.

His growing reputation helped him win a seat in the Fourth Parliament, where he began advocating for workers’ rights and labour regulations, topics that few had taken seriously before.

But it was during the Fifth Parliament that Ali Akbar Davar truly came into his own.

Ali Akbar Davar: Architect of Iran’s Modern Political Reforms

During his time in the Majlis, Davar formed close ties with like-minded figures such as Firouz and Teymourtash. Together, they founded the Revival Party—a secular, progressive movement with strong liberal and nationalist leanings.

Unlike the Socialist Party, which aimed to mobilize the lower classes and create change from the ground up, Davar believed the opposite. His strategy was clear: work with the elite, form alliances with powerful individuals, and drive reform from the top down.

And in Reza Khan, he found his changemaker.

When Reza Khan sought to turn Iran into a republic, Davar backed him.

When Reza Khan wanted the title of Commander-in-Chief, Davar worked with Moddares to make it happen.

And when it came time to abolish the Qajar dynasty, it was Davar who wrote the resolution himself.

He whipped the votes, leveraged every connection in the chamber, and personally brought the deputies to Reza Khan’s house to collect their signatures.

He established the constituent assembly and even wrote the amendments to Iran’s constitution that created the Pahlavi dynasty.

In return for his loyalty, the Shah rewarded him.

Revolutionizing Iran’s Judiciary: Ali Akbar Davar’s Bold Legal Reforms

While Teymourtash became Minister of Court and Firouz became Minister of Finance, the government appointed Ali Akbar Davar as Minister of Justice.

It was a natural fit.

Davar held a doctorate in law from Europe and was fully versed in the country’s rules and constitution.

Now, he finally had the chance to put his ideas into action—

to reshape Iran’s justice system … and leave his mark on the country’s future.

Iran’s Legal System Before the Pahlavi Dynasty

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Iran’s judicial system was one big mess of colliding ideologies.

Its system was fragmented, inconsistent, and heavily decentralized. The central government had little control, and justice was mostly handled at the local level. Tribal leaders, village elders and landlords were the main authorities in charge of resolving disputes in their communities, often using local customs and traditional practices.

The Shi’a clergy had a strong influence over religious courts. However, their rulings were often inconsistent because there was no unified or codified legal system. Different jurists interpreted laws in different ways, leading to contradictory decisions. The law mainly focused on personal behaviour and religious rituals, not on creating clear rules for governing society or limiting state power.

Secularizing Iran’s Legal System: Davar’s Efforts to Limit Clerical Power

Once he became the minister of justice, Davar used emergency powers to shut down the existing Ministry of Justice and courts for four months to start a full-scale restructuring.

Together with the help of Firuz Nosrat al-Dowleh, they unleashed sweeping changes to this branch. They dismissed corrupt and unqualified staff and replaced the fragmented, traditional system with a centralized and modern judiciary.

A major shift in Davar’s reform was the secularization of the judiciary. Tehran University’s Law College trained judges in modern law, and they applied secular legal codes. The government limited Religious courts to personal status issues like marriage and divorce. The state centralized legal authority and introduced an appeals system, replacing the old model where local clerics or tribal leaders had the final say.

Balancing Tradition and Modernity: Ali Akbar Davar’s Legal Code Reforms

In 1932, Davar also removed the clergy’s control over legal documentation by creating a system of state-appointed notaries and registrars to handle contracts, births, deaths, and marriages.

Davar’s reforms effectively ended the fragmented local, religious, and customary justice systems and replaced them with a unified, state-controlled judiciary. His changes laid the foundation for modern legal administration in Iran, and some elements—like the Civil Code, appeal courts and the jury system—remain in use in Iran’s legal system up to this day.

While Davar’s new legal codes were mostly secular, they still kept some elements of Islamic law, especially in family matters. Men still had the right to divorce their wives whenever they wanted, could have multiple wives, enter temporary marriages, and usually kept custody of children.

In other areas, the new codes significantly reduced the influence of Islam. First, they removed the legal difference between Muslims and non-Muslims—everyone was now treated equally under the law. Second, the death penalty was limited only to serious crimes like murder, treason, and armed rebellion. Third, instead of traditional corporal punishments like lashings or amputations, the system shifted toward modern punishments like long-term prison sentences.

This meant that the government needed more space to hold offending criminals.

To meet the need, Davar and Firuz Farmanfarma drew up plans to build five large prisons and eighty smaller ones.

The largest of these was the Qasr Prison.

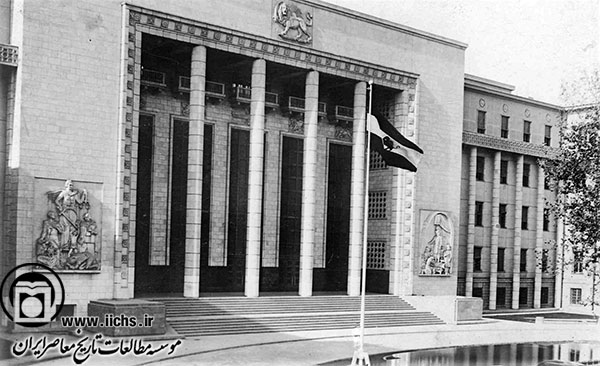

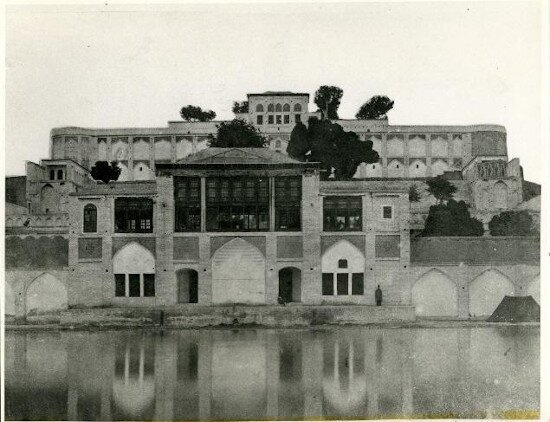

Qasr Prison: Iran’s Biggest Prison in the Pahlavi Era

The prison was built in the 1930s on the site of a former royal retreat, linking it symbolically to the Qajar dynasty that the new regime had replaced.

The prison was massive and heavily fortified—high walls, barbed wire, armed guards, and watchtowers made it clear this was a place of serious state control. It wasn’t just a prison; it was a symbol of the central government’s new authority and the shift from traditional punishment to modern incarceration.

People referred to Qasr in different ways. Some called it the “Iranian Bastille,” comparing it to the famous French prison known for political repression. Others called it the faramush khaneh, or “house of the forgotten,” meaning prisoners were expected to be forgotten by the world, and to forget the world in return.

Reza Shah’s Iran: A Tale of Modernization and Authoritarianism

Many historians agree that Reza Shah’s reign as Iran’s monarch could be broken down into two distinct periods.

In the first phase, from the early 1920s to the early 1930s, he focused on building a modern, centralized state. He introduced reforms in government, education, the military, and the economy. He expanded infrastructure, promoted Iranian nationalism, and tried to reduce foreign influence.

During this time, Iran saw new laws, improved rights for women, and greater state control over distant regions. This was the era when Iran left the Antiquated Qajari ways and entered into the modern age.

In the second phase, from the mid-1930s, Reza Shah’s rule became more repressive.

Political opponents were silenced, dissent was punished, and his government became more about personal control. He grew suspicious of those around him and removed or punished people who had once supported him. He gathered personal wealth and pushed secular reforms forcefully, which caused friction with parts of society.

His leadership turned into a cult of personality, and while authoritarian traits existed from the start, they became much more dominant in this later period.

In this second era, having a modern judicial system proved to be a double-edged sword.

Under the Qajar dynasty, enemies of the state were dealt with swiftly—murdered, exiled, or made to disappear. No process, no paperwork, no questions.

But now, with a functioning Ministry of Justice, removing someone meant going through legal motions—even if those motions were only for show.

For this delicate task, Reza Shah had the perfect soldier.

Reza Shah’s Secret Police: Mohammad Hossein Ayrom and State Surveillance

Ayrom was a loyal soldier. He was good at following orders. His work was impeccable. And most importantly, he cared for no one other than the king.

Born in 1882 in Baku, Mohammad Hossein Ayrom was a military officer who rose quickly through the ranks due to his training in Russia and fluency in foreign languages. He joined the Iranian Cossack Brigade during the Constitutional Revolution and gained favour with his superiors, especially a colonel who had high ambitions.

In 1930, following a prison riot and escape of inmates in Tehran, the then-police chief was dismissed. Looking for a loyal candidate for the vacant position, Reza Shah appointed Ayrom as head of the national police.

As police chief, Ayrom gained nearly absolute authority. The police under his command monitored citizens closely, censored the press, and kept constant surveillance over even loyal officials. His network of spies extended through all government departments, strengthening Reza Shah’s grip on power.

Ayrom’s first actions were creating a political division within the police that monitored the behaviour and speech of government officials, reporting everything directly to the Shah.

The Role of Reza Shah’s Secret Police in Iran’s Political Repression

But this “secret police” was more than just a surveillance team. It was designed for preemptive control.

Ayrom didn’t wait for the king to become suspicious. He made sure the files were ready in advance. Just in case the government needed to push, threaten, or eliminate an official.

Sometimes, these files were built through daily surveillance. Officials were followed. Their movements tracked. Their conversations recorded. Any suspicious or illegal behaviour was noted and filed.

Other times, information came from paid informants, eager to sell what they knew—or what they claimed to know—for a bit of cash.

And when there was nothing to be found, the evidence was simply fabricated.

Detailed reports would allege that certain individuals had taken bribes, embezzled funds, or acted against the interest of the state.

The system worked.

These manufactured “truths” had helped bring down Teymourtash and had justified the exile of Firouz Nosrat al-Dowleh.

Reza Shah was so impressed with Ayrom’s results that in 1933, he promoted him to Major General.

But Ayrom’s job wasn’t finished.

There was still one more person left to deal with.

The very individual who had created the entire judicial system

Ali Akbar Davar’s Financial Legacy: Reforms and Economic Diplomacy

After his radical transformation of the Ministry of Justice, Ali Akbar Davar was appointed Minister of Finance in 1933.

In this role, he oversaw a wave of state-funded projects and expanded Iran’s economic ties abroad. Trade with the Soviet Union grew through barter agreements, and in late 1935, Iran signed a significant trade deal with Germany.

Under this agreement, Germany would send industrial equipment to Iran in exchange for Iranian cotton, wood, rice, carpets, dried fruits, caviar, and precious metals.

When tensions with the British over oil escalated, it was Davar who led Iran’s delegation to the League of Nations. He successfully argued that the dispute was a bilateral matter, convincing the League to abstain from interfering.

Like Teymourtash and Firuz, Davar was a skilled bureaucrat and savvy political strategist. His European education gave him a clear grasp of international politics. His deep roots in Iran gave him the perspective to navigate its internal complexities.

He was the perfect bridge between domestic reform and foreign diplomacy.

But after returning to Iran, Davar faced a new reality.

Political Repression in Iran: The Fall of Teymourtash and Firouz

Teymourtash—his longtime ally—had died under mysterious circumstances in the very prison they had helped establish.

Firuz, his other friend, had been arrested on fabricated charges, awaiting banishment.

Reza Shah’s circle of trusted men was shrinking, and his growing paranoia cast a shadow over every remaining ally.

And soon, it would be Davar’s turn.

Reza Shah Turns Against His Minister: Final Days of Ali Akbar Davar

On February 9, 1937, Ali Akbar Davar was summoned to the palace to brief Reza Shah on a new cotton export agreement with the Soviet Union.

The meeting was short and brutal.

The Shah, visibly agitated and distracted, raised his voice, scolding Davar harshly in front of others.

When Davar emerged, he was shaken.

All the signs were there:

The indifference in the Shah’s attitude.

Davar’s shrinking role in the cabinet.

The agents trailing him—subtle, but noticeable.

He had helped build the system. He knew it too well.

And he knew exactly what would come next.

It had been ten years since the creation of the Revival Party—a decade of intense reform and transformation.

In many ways, the party had succeeded.

It had separated religion from politics, built a strong army, reformed the bureaucracy, shifted focus from foreign capital to domestic investment, and opened education to all, including women.

While the party fulfilled its mission, its founders had not been spared.

One was murdered.

One was banished.

And the third, its founder … was standing at the edge.

But Davar had never been the type to wait for fate to catch him. He had always taken control.

From leaving Iran to study in Europe, to founding a paper that shaped the national discourse, to climbing his way into parliament and reforming Iran’s justice system.

He had earned everything through force of will.

And if this was how it was going to end, then it would end on his terms.

Davar’s Tragic End: The Suicide of Iran’s Leading Reformer

The day after his meeting with the Shah, Davar carried on as if it were any other day.

He went to the Ministry of Finance, signed the letters on his desk, attended his scheduled meetings, and fulfilled every final duty expected of him.

And then, at the end of the day, he submitted his resignation.

When he returned home, he entered his study and closed the door.

There, he wrote two letters: one addressed to his wife. The other to Reza Shah.

And then, Ali Akbar Davar took his own life.

The last true ally of Reza Shah was gone.

And in a world growing ever more hostile towards the king … the Shah now stood alone.

One Response