This is the transcript for Book Two, episode 5 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: Unveiling. This story is about Reza Shah’s unveiling (kashf-e hijab) efforts and how his trip to Turkey compelled him to secularize the country.

Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

A Night to Remember

January 8, 1936.

The College for Teachers Training was one of Iran’s first institutions. A place where young women could pursue an education beyond primary school.

Originally founded during the Qajar era, it had undergone significant redevelopment under the Pahlavi dynasty. It was transformed into a fully fledged institute for women seeking higher education and a path into the workforce. It trained girls to become elementary school teachers, and graduates earned a diploma equivalent to a high school degree.

Every January, the school held a modest graduation ceremony, a small, respectful gathering.

But this year, Things were different. This year, the king himself was attending.

The ceremony began, and the host welcomed His Royal Highness, who entered not alone but with his family.

At his side: Queen Taj-al-Molouk, and their daughters, Shams and Ashraf.

As they walked in, the room fell silent.

The Queen and the princesses were unveiled. No headscarves, no hijab.

For centuries, Iranian women had covered their hair and body in public. Hijab had long been shaped by a complex mix of religious teachings, cultural expectations, and political customs …woven into the fabric of identity.

But now, Reza Shah wanted to unravel that fabric.

The year before, he had implemented a law banning the hijab in public spaces. Now he was making a statement, using his own family to set the example.

The royal family took their seats. The ceremony continued.

One by one, the girls approached the podium to receive their diplomas.

No faces were veiled. No heads were covered.

Reza Shah’s Coronation and the Birth of the Pahlavi Dynasty in 1926

“The gathering of this noble assembly, where the heart of the Iranian nation overflows with joy, delight, and devotion, stands as a testament to unity. At this moment, all across the land, the people partake in celebration, with eager and abundant joy. Not only because a new king ascends the throne of this ancient realm and places the crown of kingship upon his head, but because the age of sorrow has ended and the tides have shifted. By God’s will, the days of hardship and suffering are now behind, and the time of pride and honour has come to dawn.”

On April 25, 1926, the whole city was shut down for the coronation ceremony of the new king. But this wasn’t just another celebration. It was the beginning of a new era for Iran and Iranians. The birth of a new dynasty and the start of a new age.

A moment filled with hope. A hope that had spread across the land and given Iranians something they hadn’t felt in a long time:

a breath of fresh air.

And the new prime minister’s speech reflected that exact sentiment.

Mohammad Ali Foroughi: A Key Political Figure in Early Pahlavi Iran

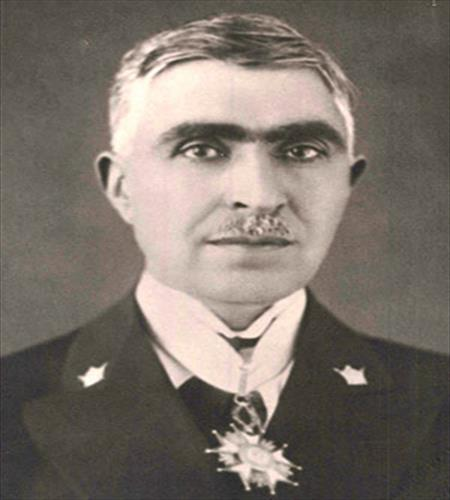

Mohammad Ali Foroughi was born in Tehran in 1877 into a respected merchant family from Isfahan. His father, Mohammad Hosein, was not only a poet and translator for the Qajar kings but also the publisher of Tarbiat, Iran’s first non-governmental newspaper. Foroughi grew up immersed in literature and language. He learned Persian and Arabic from an early age, and soon enrolled at the Dar ul-Funun school, where he excelled in foreign languages and translated works for his peers.

Initially studying medicine, Foroughi quickly realized his interests lay elsewhere. He shifted to philosophy, literature, and history, translating Western philosophers’ works and later publishing his own book on European philosophy.

Much like most of the progressive thinkers of that era, Foroughi’s political career was deeply intertwined with Iran’s Constitutional Movement.

He became a member of the Majlis in 1909 and even briefly served as its Speaker in 1912. His political influence extended into various ministerial roles, including Minister of Justice, where he introduced critical legal reforms, and Minister of Finance.

Foroughi’s presence and influence in Iranian politics were so prominent that even the coup of 1921 didn’t remove him from power. In fact, with the rise of Reza Khan, his position became more prominent.

Reza Shah and Mohammad Ali Foroughi: The Dynamics of Trust and Power

Reza Khan, seeing the knowledge and experience of Foroughi, brought him into his cabinet and eventually into his close circle.

The prime minister was an inherently suspicious man, yet Foroughi had his complete trust.

He had trusted him enough to make him acting prime minister during long absences from the capital, including the critical campaign against Sheikh Khaz’al.

So when the Majlis voted to dissolve the Qajar dynasty, it was Foroughi who stepped in once again. He took on the role of acting prime minister while Reza Khan formally resigned to prepare for his ascension to the throne.

But Foroughi’s fate wasn’t to be the last prime minister of the Qajar era.

Soon after, the new king appointed him as the first prime minister of the Pahlavi dynasty.

His presence loomed so large that during the coronation ceremony, he rode in the second carriage, directly behind the king… alongside Teymourtash,

Reza Shah’s other trusted advisor.

Yet despite Foroughi’s influence and Reza Shah’s trust, his tenure as prime minister didn’t last long. Conflicts with the minority groups in the parliament and a power struggle with Teymourtash, who wanted to be the number two of the nation, led to his resignation on June 13, 1926.

While he was no longer the prime minister, Reza Shah still had full confidence in Foroughi and appointed him as the ambassador to Turkey to solve an ever-growing crisis in Iran’s western borders:

Foroughi’s Diplomatic Role in Strengthening Iran-Turkey Relations

In the 1920s, the Iran-Turkey border had become a focal point of tension amid the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of new nationalist states. The Treaty of Kars in 1921, signed between Turkey and the Soviet Union, reshaped the region’s boundaries, sidelining Iran’s interests and legitimizing Turkish control over some territories. This exclusion from key agreements heightened tensions, especially as Turkey sought to revise borders and assert control over regions like the Ararat area.

It was during this event that Foroughi served as Iran’s ambassador to Ankara, a role that would prove very important.

At the time, Turkey was under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

Foroughi, who had become one of Atatürk’s personal friends, used their relationship to strengthen diplomatic ties. Through a mix of rapport and diplomacy, Foroughi not only diffused rising tensions but also secured a formal invitation for Reza Shah to visit Turkey.

A visit that would prove to be more than ceremonial.

Reza Shah’s Republican Ambitions and the Influence of Atatürk’s Reforms

You may remember that before abolishing the Qajar dynasty and becoming king, Reza Shah had different plans for Iran.

He had wanted to transform the country into a republic, with himself as president.

An idea we covered in the final episodes of the last season.

This ambition was largely inspired by Atatürk’s actions.

Atatürk was a military officer and leader during World War I. After the Ottoman Empire’s defeat in the war, the empire collapsed, and Turkish nationalists, led by Atatürk, opposed foreign occupation and the partitioning of their land by European powers.

In 1919, Atatürk led the Turkish War of Independence, which led to the creation of a new nation. In 1923, the Republic of Turkey was officially established, and Atatürk became its first president.

After becoming president, Atatürk introduced many reforms to modernize the country, such as secularizing the government, changing the alphabet, and giving women more rights, like the right to vote.

Clerical Opposition to Reza Shah’s Republican Dreams

The clergy were afraid that if Iran had become a republic, the same fate would follow.

Reza Shah and Atatürk had many similarities, and their visions for their respective countries seemed nearly identical.

Iran’s religious leaders were terrified that if Reza Shah succeeded in making Iran a republic, Islam would suffer the same fate it had in Turkey. That’s why individuals like Moddaress fought hard to defeat the republicanism movement.

To win over the Shia community, Reza Shah had promised that he would never undermine Islam.

He had even sworn in his oath of office to safeguard the Shia faith.

And for the early years of his reign, he held to that promise.

Reza Shah and Islam: Balancing Religion and Power in the Early Pahlavi Era

As king, Reza Shah continued to fund religious seminaries, honour senior clerics, and make pilgrimages to religious sites such as Najaf and Karbala.

His actions aimed at maintaining a positive relationship with the religious establishment.

He exempted theology students from military service and granted refuge to clerics fleeing Iraq. His regime also protected clerics who supported the government, allowing them to maintain their religious status.

Reza Shah took strong actions against secular and atheistic ideas, equating materialism with communism and banning the promotion of atheism. The education system was designed to emphasize faith in God, aligning with the view that a society governed by faith was essential for maintaining order and unity.

But much like the other aspect of his reign, the second half of his rule changed everything.

Reza Shah’s Crackdown on Religious Defiance in Qom (1928)

In March 1928, during the Nowruz celebrations, Taj al-Muluk—wife of Reza Shah—visited the shrine of Fatima in Qom, accompanied by her daughters and other women of the royal court.

The trip was meant to be a religious occasion, a symbolic gesture marking the new year.

But when they entered the shrine, some of the women had not fully covered their faces—a breach of local custom that did not go unnoticed.

One of the notable ayatollahs in the city sent a message demanding that they either respect the traditions or leave the shrine.

The message was ignored.

The Ayatollah, in protest, gathered a crowd, publicly condemning the act and demanding the departure of the Shah’s wife from the city.

Taj al-Muluk reported the incident to Reza Shah. The King, known for his short temper and need for control, was furious.

He prepared a military unit and personally led it to Qom.

The Shah entered the shrine.

His soldiers quickly located the protesting cleric.

Without hesitation, Reza Shah walked up to him and began to beat him mercilessly.

The clergy was struck down in front of the crowd, one of his ribs broken.

The people stood in shocked silence.

No one moved.

No one spoke.

From that day on, the relationship between Reza Shah and the holy city of Qom and the clergy in general was irreparably damaged.

Reza Shah’s Secularization: Challenging Religious Authority and Traditions in Iran

Reza Shah systematically curtailed the public role of Islam through a series of symbolic and legislative acts that challenged religious authority and practice. He inaugurated the next Majles without clerical presence, defying both religious custom and political decorum. He opened higher education in law and medicine to women and allowed medical students to dissect human cadavers—actions that directly contravened religious sensibilities about gender and the sanctity of the body.

Mourning rituals, a central aspect of Shi’a public expression, were limited to a single day. Mourners were also required to use chairs in mosques rather than sit on the floor, disrupting long-standing customs.

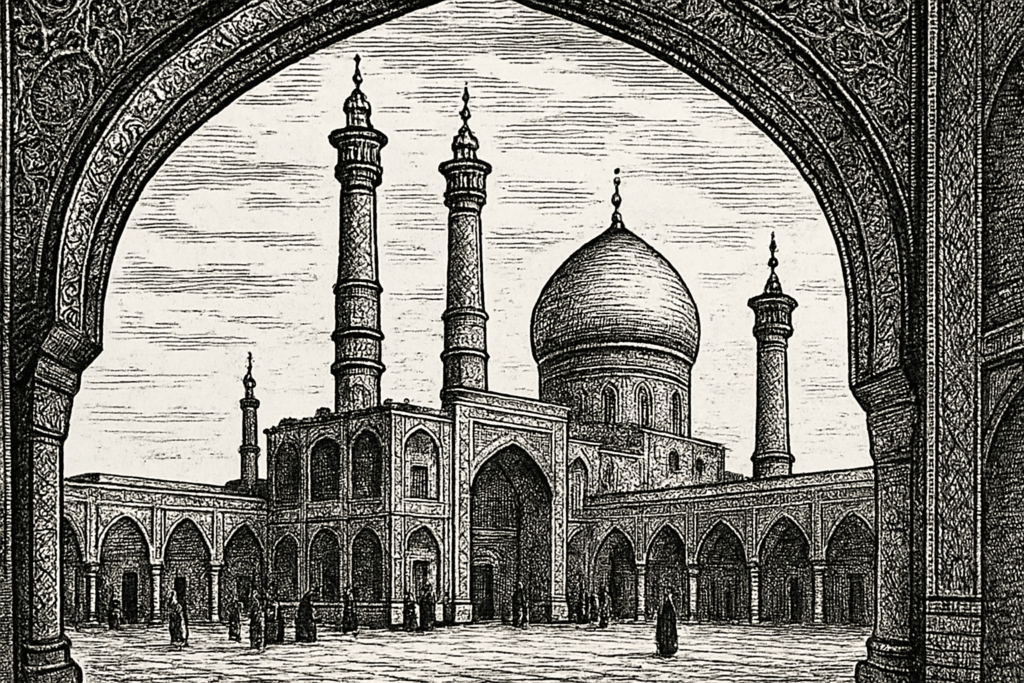

Street processions and commemorations for major religious occasions like Muharram were banned, and Religious sites, such as the Mashhad shrine and the Isfahan mosque, were opened to foreign tourists.

He also considered raising the legal marriage age, a move that would bring secular law into areas traditionally governed by religious authority.

But the real escalation happened after Reza Shah’s trip to Turkey.

Reza Shah and Atatürk: Iran and Turkey Unite

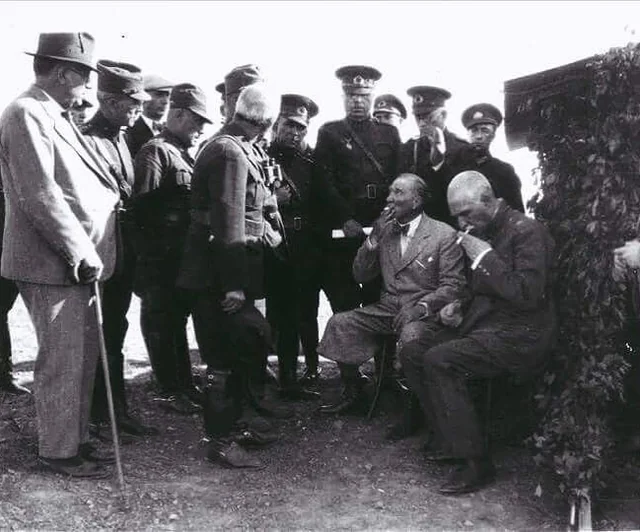

On June 12, 1934, after four days of travel, Reza Shah arrived in Turkey—his first … and last … trip as the King of Iran.

In Turkey, he was greeted by Atatürk and exchanged pleasantries with his counterpart.

While the trip was originally supposed to last 14 days, Reza Shah ended up staying there for 38.

The king, alongside Atatürk, visited Ankara, Izmir, and Istanbul, witnessing firsthand the change Turkey had undergone in just a decade.

Reza Shah and Atatürk got along well.

Despite the king’s lack of political polish compared to Turkey’s president, the two found common ground in their shared desire to modernize their nations.

Both leaders wanted to break away from the influence of the British and the Russians.

And for that, forming a strong partnership seemed obvious.

But as the trip went on, Reza Shah grew quiet.

What had started as a diplomatic visit turned into something more personal.

He became frustrated, even disheartened, as he watched how quickly Turkey was advancing toward modernity and secularism, while Iran still felt held back.

To him, the biggest obstacle was clear…

The traditional grip of religion on the people.

The experience left a mark.

And by the time he returned home, he had made up his mind.

He would double down.

And the campaign to transform Iranian society would move faster … and harder than ever before.

How Reza Shah’s Visit to Turkey Fueled His Desire for Rapid Modernization

After his return from Turkey, Reza Shah unleashed a series of controversial acts to prove to the world who’s the boss and fast-tracked the country’s modernization efforts.

Women were encouraged to unveil, starting with symbolic acts like their own daughters appearing bareheaded in public. More provocatively, he mandated that the brimmed fedora (symbol of Western modernity) replace the Pahlavi hat. It wasn’t just fashion: the brim physically prevented devout Muslims from pressing their foreheads to the ground in prayer.

And that inconvenience caused a huge rift within the muslim community.

In the holy city of Mashhad, this was seen not as reform, but desecration.

A schism formed between the newly appointed provincial governor, Pakravan, who pushed for strict enforcement of the hat law on behalf of the crown, and Mohammad Vali Asadi, the powerful custodian of the Imam Reza shrine, who warned that forcing the change would spark open revolt.

Reza Shah ignored the warning.

The Goharshad Mosque Massacre: Reza Shah’s Brutal Response to Religious Dissent

On July 10, 1935, crowds of urban merchants, villagers, and devout citizens gathered inside the Goharshad Mosque, adjacent to the shrine of Imam Reza.

There, the mosque’s preacher denounced the government from the pulpit, likening Reza Shah to Yazid, the Umayyad caliph who was reviled by the Shia followers and had ordered the killing of their third imam.

You might remember from previous episodes that the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad held immense religious, cultural, and political significance. As the burial place of the eighth Shi’a Imam, it was one of the holiest sites in their religion. Any state interference with the shrine was seen not just as blasphemy but as an assault on faith, identity, and local autonomy.

For four days, the protest grew as local police and military units hesitated to storm the holy site. Officials in Mashhad were paralyzed and scared. Scared of the people and of Reza Shah’s wrath at their inactivity.

Then came the reinforcements from Azerbaijan, under direct orders from Tehran.

What followed was a massacre.

Machine guns were turned on the crowd. Men, women, and children were gunned down in the courtyard of a holy site.

No one was spared.

Eyewitnesses claimed the dead numbered in the hundreds. Some say even thousands.

Official figures were far lower, but even government sources admitted to a bloodbath.

But the punishment wasn’t only on the dissenters.

Reza Shah’s Break with the Shia Clergy: Aftermath of the Mashhad Massacre

Asadi, the custodian of the Imam Reza shrine, was accused of inciting the protests.

He was arrested by the King’s Guard and taken into custody.

Asadi’s son was married to Foroughi’s daughter. And Foroughi, then serving his second term as prime minister, took the matter to the Shah personally, asking for leniency.

It was a mistake.

To Reza Shah, this wasn’t a plea for justice.

It was a breach of trust.

How could Foroughi, his first and most loyal prime minister, stand up for someone who had defied the crown?

You might remember that in the second part of his reign, Reza Shah was growing more and more paranoid of those closest to him.

From Prime Minister to Banishment: Mohammad Ali Foroughi’s Fall from Power

Foroughi was Reza Shah’s first prime minister. He was one of his confidants and had represented Iran in international communities. He had even been chair of the League of Nations. But none of this was enough.

Foroughi wouldn’t be spared either.

Shortly after his appeal, Foroughi was removed from office as prime minister and was placed under house arrest. Now Shah’s soldiers were stationed outside his home, watching every move, documenting every visit.

Another trusted confidant … erased from the inner circle. Though Foroughi’s story with the Pahlavi dynasty wasn’t quite finished … at least not yet.

As for Asadi, the shrine’s custodian…

He was tortured, and on December 20th, 1935,

executed by firing squad.

The Mashhad massacre shattered Reza Shah’s relationship with the Shia establishment, but most prominent Shia voices in Qom, Isfahan and Iraq remained silent, afraid of the king’s retaliation, and that silence gave Reza Shah the confidence to push even further.

The king abolished the tradition of announcing Ramadan with cannon fire.

He ended shortened workdays during the fasting month.

He transferred clerical requests and affairs from the Office of Religious Endowments

to the Ministry of Education, secularizing the administration of Islam itself.

But none of these changes stirred as much outrage as what he did next.

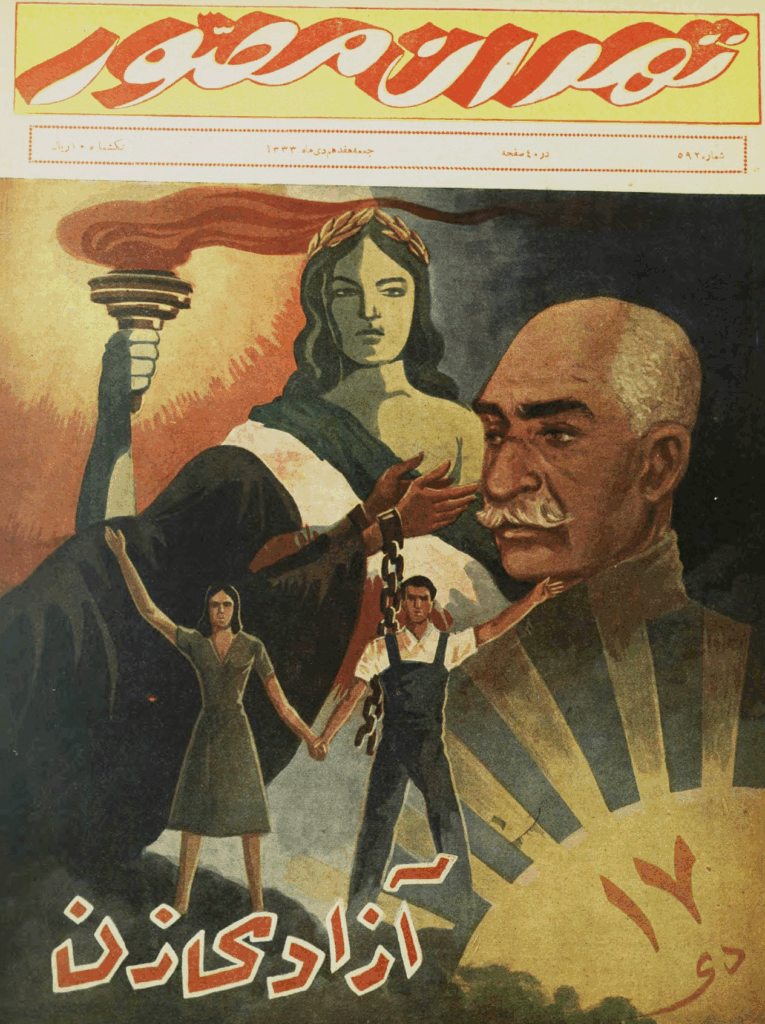

Kashf-e Hijab: Reza Shah’s Controversial Unveiling Law of 1935

In 1935, under Reza Shah’s rule, a sweeping state-led campaign to modernize Iranian society led to the formal launch of Kashf-e Hijab or unveiling, a law banning the hijab for women.

The practice of hijab in Iran had deep historical roots, influenced by cultural norms and religious principles. After the Arab conquest of the country, Hijab gradually became a symbol of male honour, family virtue, and tightly linked to social order and gender boundaries. This tradition persisted through the Qajar era and was further entrenched as a sign of moral and sexual purity.

The unveiling process had started long before the Shah’s trip to Turkey, however. In the late 1920s, women’s groups had already started voluntary unveiling in the big cities. By 1932, unveiling was encouraged for schoolgirls and the wives and daughters of civil servants. But all these were in niche groups and limited settings.

In 1935, this unveiling became a mandatory, state-enforced policy.

Backed by government initiatives like the founding of the Women’s Center, the policy aimed to visibly integrate women into public life, mirroring what Reza Shah had observed during his visit to Turkey.

Ministers were instructed to appear publicly with unveiled wives, and hijab was prohibited in schools, though the policy met little initial resistance.

Reza Shah believed the veil symbolized backwardness and compared it to a festering wound that had to be removed. He rejected any compromise, such as replacing the chador with a loose overcoat, insisting on fully European attire for women.

The Social Impact of Reza Shah’s Unveiling Policy: Resistance and Reformation

The unveiling policy culminated in a symbolic act on January 7, 1936, when the Queen and royal daughters appeared unveiled at a public graduation ceremony.

Reza Shah closely supervised the enforcement of unveiling, but it was met with significant social tension. Violent scenes of police forcibly removing women’s chadors, the dismissal of officials who resisted the policy, and widespread disregard for conservative opposition created a tense and controversial atmosphere around the initiative.

Older women, who had rarely left the inner quarters of their homes in adherence to Sharia law, chose to remain indoors permanently, fearing the dishonour that removing their naqabs and chadors might bring. In contrast, younger generations were more willing to break free from traditional constraints and embrace the change.

The king himself was a conservative man and believed in old-fashioned values. He wasn’t comfortable with his family removing the veil and appearing without it in public, but he strongly believed that this was a path for a better country. To truly usher in a modern age, women had to be welcomed back into society and take a bigger role in it, even if it was by force.

Those who failed to do so were summoned to the police station and government officials were required to force the mandatory unveiling in the jurisdictions.

Reza Shah’s Final Days: A Divided Iran Amidst Reforms and Resistance

The unveiling of women in Iran didn’t just provoke religious outrage—it struck at the heart of social conservatism.

In Turkey, the transition had been gradual, often optional.

But in Iran, Reza Shah forced it … and that left a bitter taste.

Whatever goodwill his reforms had built in the previous decade was wiped away instantly.

A British diplomat in Tehran even invoked Napoleon to warn the court!

“Religion is excellent for keeping common people quiet.

It is what keeps the poor from murdering the rich.”

Waging war against the Shia clergy was more than reckless … it was entering uncharted territory.

Since the days of the Safavid dynasty, Shia Islam had been woven into Iran’s cultural fabric.

It shaped not only faith, but law, identity, and power.

To strip that away was to strip the country of its anchor.

And in its place, there would be nothing but anarchy.

By now, Reza Shah had isolated himself completely with no allies by his side,

waging a war with one of the country’s oldest institutions.

And behind the curtains, a catastrophic global conflict was slowly taking shape.

All the ingredients were in place for a dangerous showdown—

and a tragic end to a once-promising empire.