This is the transcript for Book Two, episode 9 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: World War II. As Iran announces its neutrality, its friendship with Germany becomes alarming for the Allies. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

September 1, 1939, started like any other day in Warsaw, Poland. Shops opened, trams rattled down crowded streets, and children chattered on their way to school. No one knew that by mid-morning, their lives would change forever.

The tension that had been there for months.

Adolf Hitler, who had led the Nazi Party to power in 1933, had spent six years transforming Germany into a dictatorship. He rebuilt its military and defied the Treaty of Versailles. His ambition to expand eastward became clear as Germany annexed Austria in 1938 and then dismantled Czechoslovakia, without much protest from Europe’s major powers. By late August 1939, Hitler signed a secret pact with the Soviet Union, agreeing to carve up Poland between them.

Now, with his armies massed on the border and the world holding its breath, the final act of aggression was ready to begin.

The German Invasion of Poland and the Start of WWII

In the early light of day, German tanks roared across the border, treads grinding the earth like a monstrous machine. Dive bombers screamed overhead, dropping bombs that split buildings open and churned streets into dust.

The Luftwaffe painted the sky with black smoke and fire, turning morning into a living nightmare.

Families fled through the chaos, clutching their children and whatever they could carry, as the familiar streets of Warsaw transformed into a war zone.

The Germans called it blitzkrieg—lightning war—a method meant to paralyze resistance with speed and overwhelming force. Columns of infantry followed the tanks, bayonets gleaming, advancing like a relentless tide. Polish defenders, outgunned and outnumbered, fought back.

But against the mechanical onslaught, courage alone wasn’t enough. It was a war like no other. Not even the memories of the Great War came close. This was worse.

Fast. Brutal. Deadly.

By nightfall, the world knew something immense was on the horizon. By week’s end, all the major powers had taken sides. And by the end of the year, the war would consume the entire globe. Including a country far in the east, trying once again to cling to neutrality to save itself.

A vision that was always doomed to fail.

A Puppet or a Player? Reza Shah’s British-Backed Rise

When Reza Shah came to power, many believed he was nothing more than a puppet king. A figure placed on the throne by the British to secure their influence over the country.

After all, Reza Khan’s meteoric rise had been shaped by British support:

Towards the end of the First World War, General Ironside, who had taken command of the Cossack Brigade following the collapse of the Russian Empire, had recognized Reza Khan’s military talent—and his deep hostility towards Russian Cossack officers. Ironside placed him in charge of the brigade, making him the most powerful military figure in Iran.

The 1921 coup that elevated Reza Khan to Minister of War was, in the eyes of many Iranians, a “British plot.” The level of planning and financial backing required for such an operation was far beyond the reach of a single Iranian officer and a distant journalist working on their own.

The suspicion only grew stronger in 1933–34, when the Shah signed a new agreement with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. In exchange for a measly 4 percent increase in royalties, the Shah extended the company’s concession until 1993.

To many, it was the final proof that despite all his patriotic speeches, the Shah was ultimately in London’s pocket.

But the Second World War changed everything. It challenged that belief and revealed the truth behind the throne.

How Reza Shah’s Domestic Reforms Challenged British Interests

Even before the European nations began their second major conflict in less than 50 years, Reza Shah’s drive to centralize power in Iran had already brought him into conflict with British interests.

The campaign against Sheikh Khaz’al in Khuzestan had put him in direct conflict with the Western superpower, weakening the power of the tribal leader who had once been backed by the British.

Economically, Reza Shah took bold steps to undermine British privileges. In 1928, he abolished the “Capitulations”, ending the extraterritorial rights enjoyed by Europeans, which alarmed British officials. He also took control of Iran’s financial institutions, transferring the right to print money from the British Imperial Bank to the newly established National Bank of Iran.

His growing dissatisfaction with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) reached its peak in 1932, when he threw the D’Arcy concession into the fire, challenging one of Britain’s most important economic interests in Iran. Even though a new agreement, without much change, was reached in 1933, that one act significantly strained the relationship.

Reza Shah’s foreign policy, rooted in the pursuit of Iran’s full independence, further complicated relations with Britain. He insisted that Iran be treated as an equal among nations and refused to accept British interference.

When the new dynasty was formed, the British believed that Reza Shah would give them a stable government and safeguard their assets. But as the king grew more confident in his position, the status of his country, and the strength of his military, he began to reject the influence of outside players more and more.

And that shift in attitude wasn’t just limited to the British.

Iran-Soviet Relations After the Russian Revolution

When the Russian Empire collapsed at the end of the First World War, and the Soviet Union rose from its ashes, a new chapter in Iran-Russia relations began.

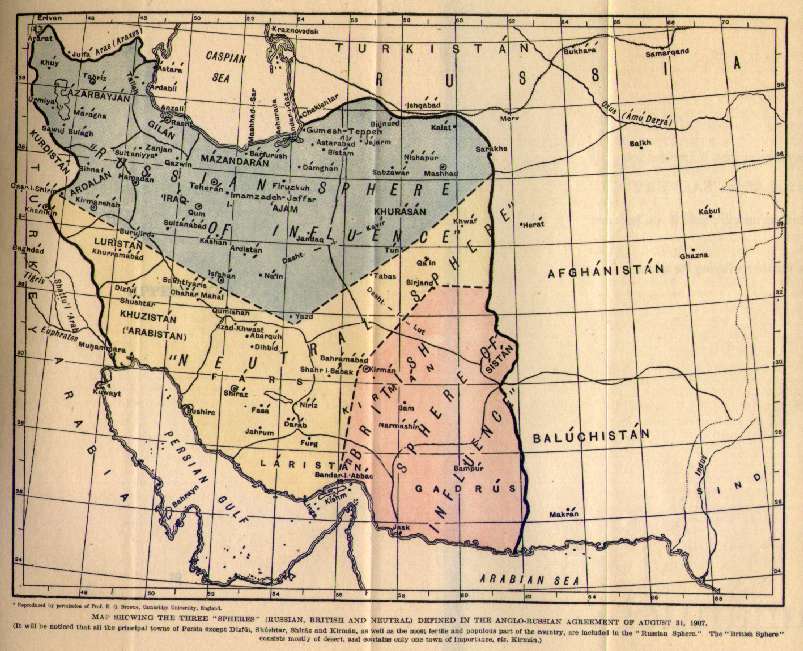

You may recall from book one how the old Russian Empire and the British had divided Iran between themselves. The Russians also exerted immense political influence by backing the Qajar kings. The establishment of the soviet union offered a fresh start for the two countries.

In 1921, Iran and the Soviet Union signed the Treaty of Friendship, annulling all previous imperialist privileges in Iran. This treaty also led to the formation of the “Iran-Soviet Joint Company” to exploit the Caspian Sea’s rich fisheries.

Through the 1920s, both sides were eager to build on that fresh start. They launched joint ventures in cotton, silk, and fishing. Despite the challenges of the global economic depression and a shift towards state-controlled economies, the Soviet Union soon became Iran’s top trading partner.

Reza Shah even made a move that rattled the British: he elevated the Soviet legation to embassy status in 1925. A clear sign that he wasn’t afraid to challenge Britain’s grip on his country and look to Moscow for a new balance.

But the honeymoon couldn’t last forever.

The cracks were there, waiting to split open.

The Rise of Communist Movements in Iran

Before Reza Shah’s rule, left-wing ideas had already begun to develop in Iran. They gained more prominence from the global communist movement and the presence of the soviet union on the northern borders.

At first, socialist and communist movements saw Reza Khan as a potential ally—a reformer who might finally bring change after the stagnant days of the Qajar dynasty. But as his grip on power tightened, the optimism faded. His iron-fisted methods turned even his former supporters against him.

Reza Shah’s transformation into an authoritarian monarch drew a sharp line between himself and Iran’s left-wing thinkers and students. They saw him as a “feudal” king, serving the interests of the wealthy elite rather than the people.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the Communist Party in Iran faced relentless repression. Arrests, censorship, and intimidation became the state’s tools to silence opposition. Yet, despite the government’s efforts, leftist ideas only spread further, especially among the young and educated.

These activists formed trade unions and pushed for workers’ rights, igniting significant labour strikes like the 1929 oil workers’ protest in Abadan and the 1931 textile workers’ strike in Isfahan.

To Reza Shah, every spark of resistance was a threat to his rule. A threat he couldn’t afford to ignore. In his eyes, the communists weren’t just ideological opponents; they were enemies of the very stability he had fought to build.

Iran’s 1931 Security Law and Its Impact on Political Dissent

To fight these growing ideas, the government passed a law in Iran on June 12, 1931, called the “Law on the Penalization of Those Who Endanger the Security and Independence of the Country.”

This law made it illegal to form, join, or lead any political group that opposed the monarchy or supported communism. Those who dared to participate could face imprisonment for three to ten years. It also criminalized any attempt to separate parts of Iran or undermine its independence. The harshest penalty (life imprisonment) was reserved for those deemed the greatest threat.

Even more chilling, the law stated that anyone who took up arms against Iran, whether alone or with foreign help, would face death.

An important aspect of the law was its betrayal of trust: anyone who informed the authorities about these groups was granted immunity, escaping punishment by turning in their own comrades.

The law also reached into the realm of ideas. It made it illegal to promote any thought against the monarchy or in favour of the causes it sought to suppress. This included actions within Iran and beyond its borders, with punishments ranging from one to three years in prison. Even Iranians who acted abroad could be arrested upon their return.

Breakdown of Iran-Soviet Ties and the Turn Toward New Alliances

But more than any single measure, this law cracked the fragile relationship between Reza Shah and the communists in the north. In his eyes, the Soviets were the architects of communist ideology in Iran—agitators sowing discord against his government.

What had once been a cautious friendship was now a bitter standoff.

So by the 1930s, Iran and the Pahlavi dynasty had distanced themselves from both the British and the Russians.

That left them alone… Without the support of either of the region’s dominant powers.

They needed new allies.

Nations that didn’t carry the baggage of old treaties, foreign occupation, or decades of betrayal.

And what better partner than a country with which Iran shared an ancestral heritage with?

Or at least … wanted to believe it did.

Why Iran Chose Germany Over Britain and Russia

Iranian intellectuals had long felt a special bond with Germany. Back in the 1910s, during the First World War, many saw Germany as the only counterweight to the British and Russians—two empires that had carved up their homeland and looted its resources.

In Book One, we explored how a group of influential Iranians even formed a shadow government, propped up by German support. But Germany’s defeat shattered those ambitions. The dream dissolved, and the people behind it were forced to flee.

Yet as Germany slowly regained its footing in the 1920s, Iranian diplomats quietly reassessed the potential of a renewed friendship.

Then came the rise of the Nazi regime … And Iran found itself drawn into Germany’s orbit once again.

In 1934, Alfred Rosenberg, one of Hitler’s chief ideologues, proposed that Iran should become a cornerstone of Nazi plans to expand their influence in the Middle East. He believed Germany should help Iran modernize and rise as a regional power to counter British and Soviet influence.

Ancestral Illusions: The Myth of Aryan Brotherhood

In Nazi Germany, the idea of Aryan kinship had become a central pillar of the regime’s worldview.

Hitler and other Nazi leaders built their ideology on the myth of an “Aryan race”—a race that, in their telling, had once built the greatest civilizations on Earth, only to fall through racial mixing and betrayal. Germany had declared that they were the modern heir to this legacy, the torchbearer of the “pure” Aryan spirit that -they claimed- resided especially in the northern European bloodline.

This racial narrative resonated deeply with the story Reza Shah was crafting in Iran.

In the 1930s, as he worked to shape a national identity, Reza Shah turned to the ancient Persian Empire—the Achaemenids and the Sassanids—to claim a lineage of greatness.

It was his way of cementing his rule and advancing his modernizing agenda.

Aryanism, as a racial idea, was central to this narrative.

The term “Aryan” had deep roots in Iranian history; ancient peoples of Iran had once proudly called themselves by this name. Reza Shah’s decision to rename the country from Persia to Iran was in part a bid to align the nation with this Aryan heritage.

But there was a problem with this argument.

How the Myth of Aryan Identity Shaped Iran-Germany Relations

The term “Aryan” itself had a far older and more complex meaning than the Nazis ever acknowledged.

It originally referred to a group of Indo-Iranian-speaking peoples who had spread across Central Asia, South Asia, and parts of the Middle East and Eastern Europe during the Bronze and Iron Ages. These ancient Aryans were worlds apart from the Germanic peoples who, centuries later, the Nazis would claim as their racial ancestors.

The Germanic tribes and the Persians, while sharing a distant lineage, had been culturally and linguistically distinct for thousands of years. Their last significant shared ancestry dated back more than six millennia.

Yet that didn’t stop the Nazi regime from exploiting the Aryan myth.

How Nazi Germany Sold Reza Shah a Dream of Power

They seized on the name to build a bridge to Reza Shah’s Iran, hoping to bind the country to their cause against British and Soviet power. German newspapers printed glowing stories about the king of Iran. The Nazi party founded a chapter in Tehran. And Adolf Hitler himself extended an invitation for Reza Shah to visit Germany.

“His Imperial Majesty – Reza Shah Pahlavi – Shahanshah of Iran – With the Best Wishes – Berlin 12 March 1936 – Adolf Hitler”

Reza Shah welcomed this new bond.

He found the idea of Aryan kinship intoxicating.

It was more than just a political alliance; it was a chance to imagine himself at the helm of a greater destiny.

Through Nazi unity, he believed, he could strengthen his rule and perhaps extend his reach beyond Iran’s borders. For him, it was a path not just to power but to a new era of national pride.

Reza Shah’s aim was clear: to harness Germany’s economic and political support to transform Iran’s economy and build a modern nation.

German companies quickly found their place in Iran’s industrial landscape. Reza Shah saw Germany as a symbol of progress—a country that could offer technology, investments, and expertise, while also taking advantage of Iran’s natural resources.

German Engineers, Iranian Soil: The Military and Industrial Connection

There’s debate among historians over how receptive Reza Shah truly was to Nazi ideas and racial theories. But one thing was undeniable: the two countries shared a mutual attraction. Germany didn’t carry the baggage of Russian and British colonialism, and thanks to the myth of shared Aryan ancestry, it seemed like the ideal partner for the king.

The Pahlavi brand of nationalism was never about democracy or liberty. It was about loyalty to the crown and pride in a renewed cultural identity—an approach that closely mirrored the nationalism rising in Nazi Germany. Like Hitler, Reza Shah cultivated a powerful cult of personality. He believed that only a strong leader could revive Iran’s greatness.

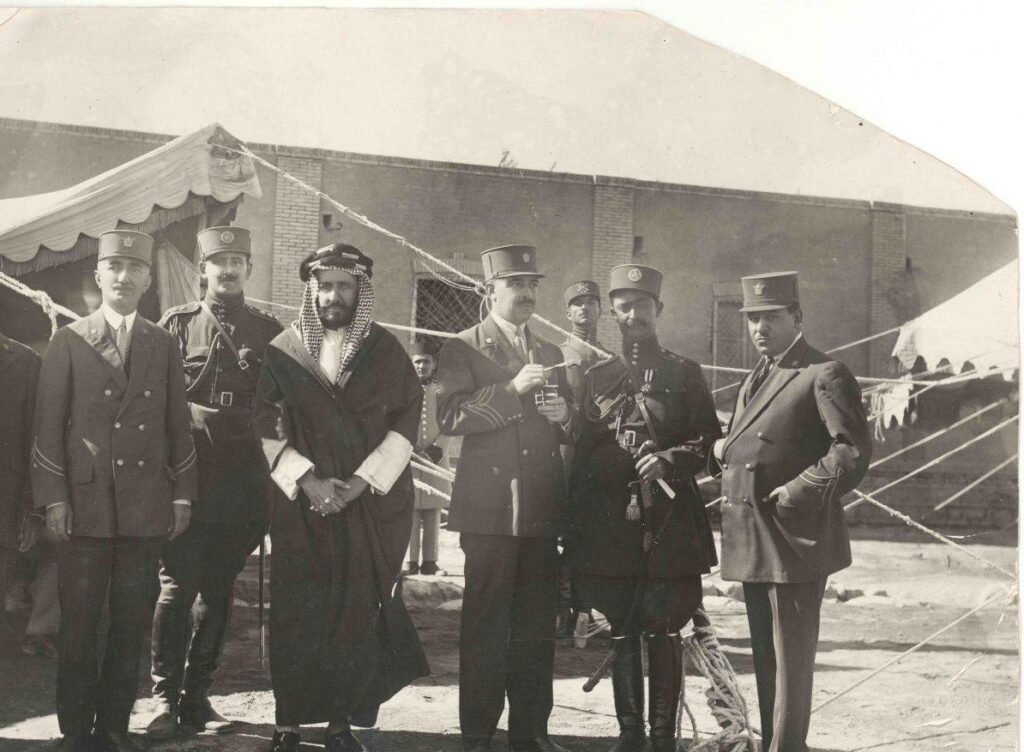

He looked to the German military as the embodiment of modern power. It wasn’t long before German officers were helping build arms factories and shaping a modern Iranian army.

Neutral but Not Invisible: Iran’s Risky WWII Balancing Act

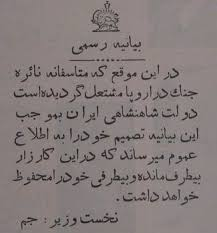

Despite all of this, when Adolf Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Iran wasted no time in declaring its neutrality in what would soon become the Second World War. The government was smart enough not to directly tangle itself with disputes of other nations.

But for Reza Shah and his dynasty, staying neutral was easier said than done.

Iran continued to trade with Germany and even sought to buy weapons from them, while at the same time demanding higher oil royalties from the British and sparring with Moscow over trade concessions.

It seemed Reza Shah was too confident, too certain of Iran’s importance, too assured in its neutrality to worry about the storm brewing in Europe.

A confidence he would soon come to regret.

The British Influence: Iraq Post World War One

It all started in Iraq, the newly formed nation that shared Iran’s western border.

Iraq was born in the aftermath of World War I, carved from the remnants of the Ottoman Empire.

The League of Nations handed the British a mandate over the region, giving them the power to shape its destiny. In 1921, they crowned King Faisal I, but beneath the veneer of independence, Iraq was still firmly under the British thumb, especially in matters of defence and foreign policy.

Though officially independent by 1932, the British grip remained strong, particularly over Iraq’s oil fields.

Just like Iran, Iraq’s strategic importance made it a prize, and every year, the people’s resentment toward British influence grew.

Fueled by this dissatisfaction and the rise of Nazi Germany, some Iraqi leaders began to look to Berlin for support, hoping the Axis could help them challenge British dominance.

The Baghdad Spark: Nazi Influence and the Iraqi Coup

In May 1941, a group of pro-Nazi officers launched a coup, determined to overthrow the pro-British government and align themselves with the Axis.

The British were quick to respond.

British forces, joined by loyal Iraqi units, crushed the rebellion in a short but fierce campaign, known as the Anglo-Iraqi War. Their goal was clear: to restore their hold over Iraq and keep it from becoming a Nazi ally.

The coup collapsed, Iraq returned to the British sphere, and Rashid Ali al-Gaylani, the coup’s leader, fled to Iran, seeking refuge in a land that was itself on the brink of crisis.

The coup in Iraq had rattled the British.

It proved to them that Germany wasn’t just fighting in Europe, it was making moves in the Middle East too.

The presence of Rashid Ali in Iran, along with the many German experts, technicians, and spies who had made their way into the country, sent alarms ringing in London.

Britain knew it couldn’t afford to lose Iran, not with its crucial position and its oil reserves.

Then, in late June, the situation spiralled even further.

When Hitler Turned East: Why Iran Suddenly Mattered

On June 22nd, Germany shattered the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, launching a massive offensive against the Soviet Union.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had been signed in August 1939. It was a temporary truce between two ideological enemies. Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Each side promised not to attack the other and agreed, in secret, to divide Eastern Europe between them. For Hitler, it meant he could invade Poland without worrying about the Soviets, sparking World War II. For Stalin, it bought him time.

Now, Hitler had torn it up, making the Soviet Union an ally of Britain and the Western powers, practically overnight.

What was once a balancing act for Reza Shah had turned into a high-stakes game where the survival of his country—and his dynasty—hung in the balance.

Initially, the Germans were terrifyingly successful in their push into Russian lands. They advanced more than five hundred miles, driving deep into Soviet territory and right up to Moscow’s doorstep. Even Stalin—Stalin-the iron-fisted ruler of the Soviet Union—went into hiding for days.

But there was more at stake than just the war.

A Nazi victory in Russia would create a power vacuum across Eastern Europe—one that Germany could fill unchallenged.

Adittionally, if Russia fell, it could have created a power vacuum in Eastern Europe, potentially allowing Nazi influence to spread uncontested.

So the British had to support the Soviets …no matter what.

And the only reliable way to get resources into Russia was through Iran and its railways and roads.

No Way Out: The British and Soviets Give Iran an Ultimatum

That meant neutrality was no longer an option for Iranians.

They either had to stand with the Allies … or become their enemy.

The first move came in the form of an ultimatum.

The British demanded that Reza Shah expel all the German personnel and technicians working in Iran.

The Shah deported some, but not all. A gesture meant to show independence, to say Iran made its own decisions.

But that only angered both the Germans and the British.

Then came a second warning.

The Allies asked for transit rights, permission to move troops and supplies through Iranian territory.

Once again, the answer was no.

Maybe Reza Shah misread the war, thinking Europe’s flames wouldn’t reach his doorstep.

Maybe he believed Iran’s neutrality still held weight. Or maybe he thought the army he’d built would protect him.

Or perhaps, he was sure the Germans would win—before any real consequences arrived.

He was wrong.

On all counts.

August 25, 1941: The Day the Allies Invaded Iran

At dawn on August 25, 1941, Reza Shah was woken with a message:

Iran was under attack.

By land, air, and sea.

From the north, from the south, from the east, and from the west.

British and Soviet forces had launched a full-scale invasion.

Every front.

Every direction.

Their mission was clear:

Remove the king.

And end his dynasty.

In the season finale of The Lion and the Sun, Reza Shah’s reign comes to an end.