The “Lion and the Sun” emblem is not just a symbol; it is a narrative woven into the fabric of Persian history, embodying the essence of power, divinity, and national pride. This iconic motif has traversed centuries, adapting and enduring through various cultural, astrological, and royal narratives. Let’s delve into the origins, evolution, and significance of this profound emblem, exploring why it continues to captivate and represent Persian identity even today.

From Myths to Reality

In the 12th century, the Seljuk Empire sprawled under the rule of Kaykhusraw I, a monarch whose heart belonged to a woman celebrated across Persia for her unparalleled beauty. Stories of her allure spread far and wide, drawing crowds eager for just a fleeting glimpse of her face. “Like a ray of sunshine”, those who saw her remembered.

Compelled by profound love, Kaykhusraw yearned to etch her beauty into the currency of his realm, a testament for all time. However, his council, devout Sunni Muslims, balked at the notion. The public depiction of a woman’s face, they argued, stood in contradiction to their beliefs.

Kaykhusraw, unfazed by their concerns, insisted on a resolution.

Days later, they came back with a solution. Meaningful gestures were not about literal acts, they were about showing love through nuanced symbols. And they had the perfect idea.

If the beauty of Kaykhusraw’s wife was like a ray of sunshine, why not show it as a sun on their coins, shining behind the figure of the king, depicted as a lion?

The Dawn of Divinity: Exploring the Sun’s Symbolic Meanings in Iranian Heritage

The sun symbol in Persian history is deeply interwoven with the region’s ancient religious and cultural practices, particularly through the worship of Mithra and the emblematic Faravahar.

Mithraism centers around the worship of Mithra, the Iranian god of the sun, justice, contract, and war, predating Zoroastrianism. Mithra was revered as the most significant deity in the pre-Zoroastrian Iranian pantheon, embodying the god of contract and mutual obligation. His association with the sun—seen as the all-observing entity that oversees everything—placed him at the core of oaths and justice, ensuring good relations and interpersonal communication among people. The Greeks and Romans later recognized Mithra as a sun god, highlighting his role in war, justice, and as a mediator ensuring the king’s mutual obligations with his warriors

The Faravahar, one of Iran’s most recognized and ancient symbols, predates Islam and has become a cultural and secular icon among Iranians.

Its origins trace back to the pre-Zoroastrian winged sun used by ancient Near Eastern powers, including Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The Zoroastrians adopted this symbol, notably used in Neo-Assyrian iconography, representing royal power backed by divinity. The Faravahar’s depiction on Achaemenid kings’ tombs and on coinage demonstrates its enduring significance. Even after the Arab conquest, Zoroastrian traditions like Nowruz and Mehregan continued to reflect the Faravahar’s cultural relevance. In modern times, despite the Islamic Revolution’s ban on pre-Islamic symbols, the Faravahar has remained a prominent national emblem, symbolizing Iranian heritage and identity

The Lion in Ancient Persia: Power and Guardianship from Persepolis to Sasanian Empire

The lion symbol’s presence in Persepolis and its general significance within the Achaemenid and Sasanian empires can be attributed to its symbolic representation of power, guardianship, and royal authority. Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire, showcases numerous reliefs featuring lions, which are believed to symbolize the king’s might, the protection of the empire, and the defeat of chaos, aligning with the lion’s attributes of strength and dominance.

These depictions are integral to understanding the art and ideology of the Achaemenid period, reflecting the empire’s values and the lion’s role in ancient Persian cosmology and royal symbolism.

Similarly, in the Sasanian Empire, lion motifs were prevalent in art, coinage, and royal insignias, symbolizing power, courage, and nobility. The Sasanian rulers, like their Achaemenid predecessors, utilized lion imagery to represent their divine right to rule and their role as protectors of their land and people. The continuity of lion symbolism from the Achaemenid to the Sasanian era underscores its enduring significance in Persian cultural and political iconography.

The specific mention of lions in the context of Persepolis and broader Achaemenid and Sasanian iconography underscores their importance across various Persian dynasties. These symbols served not only as decorative elements but also as powerful expressions of royal authority, divine protection, and the cosmic order maintained by the Persian empires.

The Birth of the Lion & Sun: From Seljuk Coins to Safavid Sovereignty

The first official use of the Lion and the Sun symbol was in the Seljuk Empire. It appeared under the rule of Kaykhusraw II. Coins from the 13th century display this symbol. Kaykhusraw II ruled as the Sultan of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum from 1237 to 1246. He used this emblem on his coinage. The likely reason was to exemplify his power. This early adoption signifies the symbol’s integration into official state insignia and currency. It highlights its importance in representing authority and sovereignty.

In the Safavid Empire, the Lion and the Sun symbol began to officially represent two pillars: the state and religion. This era lasted from the early 16th to the 18th century. During this time, the symbol evolved to reflect the Safavid dynasty’s ideals and governance. The lion symbolizes the state’s power and might. The sun represented the light of religion, bringing wisdom and guidance. This interpretation had deep roots in Persian mythology and Islamic sources. It connected Iran’s historical and spiritual lineage with significant figures. These included Jamshid, the mythical king, and Ali, the first Shia Imam.

The Safavids adopted the Lion and Sun symbol as a strategic move. It helped distinguish Iran’s identity from neighbouring powers, especially the Ottomans with their crescent moon. By choosing this symbol, the Safavids emphasized both the spiritual and temporal authority of the Shah. This move forged a distinct Iranian identity. It highlighted their role as protectors and promoters of Twelver Shi’ism. This set the stage for Iran’s emergence as a unified nation-state. It fostered a strong sense of national consciousness.

The Lion & Sun Through Ages: From Qajar Modifications to Pahlavi’s National Emblem

Qajar Dynasty

By the time of the Qajar dynasty, The Lion and Sun symbol underwent significant modifications, including the addition of a sword and crown to the lion, to explicitly represent the military prowess and royalty of the state. This period marked a consolidation of the symbol’s association with the monarchy, as well as a shift towards more nationalistic interpretations, tying it back to pre-Islamic Zoroastrian traditions and emphasizing its ancient heritage as nearly three thousand years old.

The Imperial Order of the Lion and the Sun was established by Fat’h Ali Shah of the Qajar dynasty in 1808, further institutionalizing the symbol’s significance. This order was initially intended to honour foreign officials but was later extended to Persians for their services to the nation. By the end of Fath’ Ali Shah’s reign, the Lion and Sun symbol, especially represented with Ali’s (the first Shi’ite Imam) sword, Zu’l-faqar, became a combined emblem of the state, monarchy, and the Iranian nation itself, symbolizing a blend of martial valour and royal dignity.

Under Nasir al-Din Shah, the emblem continued to evolve, reflecting variations in its depiction, from seated, swordless lions to standing, sword-bearing ones. By February 1873, the issuance of the Order of Aftab marked another milestone in the symbol’s official use and representation, showcasing the deep-rooted symbolism and its national significance in Iranian culture and governance.

Constitutional Revolution

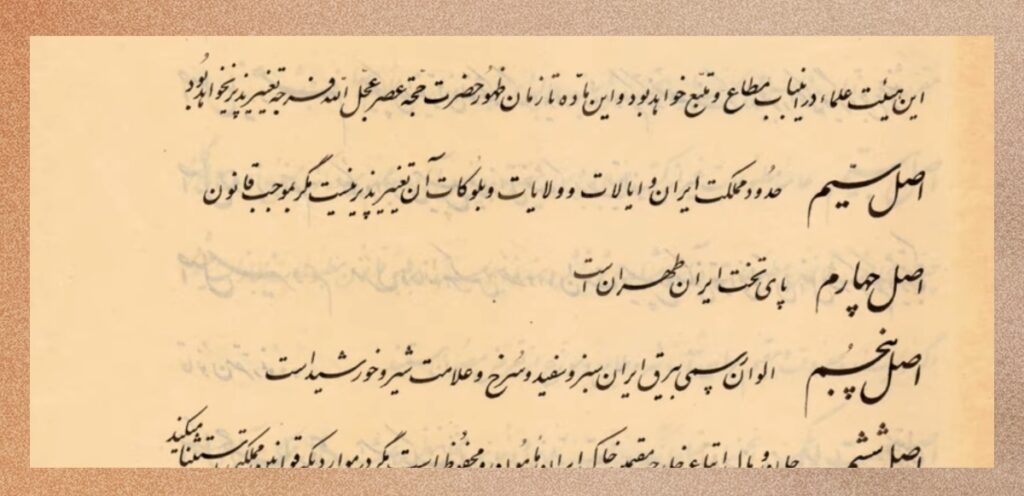

After the Constitutional Revolution which took place between 1905 and 1911, the use of the Lion and Sun symbol in Iran’s national flag was solidified in Iran’s newly written constitution. This period marked a significant transition towards constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy in Iran under the Qajar dynasty. The revolution led to the establishment of a parliament, and it was a pivotal moment that opened the way for the modern era in Persia. Shah Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar signed the 1906 constitution shortly before his death, which was a crucial step in formalizing new national symbols and institutions, including the flag featuring the Lion and Sun symbol.

The modern tricolour flag of Iran, incorporating the Lion and Sun symbol in the center with red, white, and green colours, was officially adopted following the Constitutional Revolution. Specifically, the fundamental law incorporated on October 7, 1907, showcased the flag with the Lion and Sun symbol. A decree in 1910 further specified the exact details of the symbol, including the position and size of the lion, its tail in an italic “S” shape, the sun, and the sword, marking the Lion and Sun symbol’s permanence on Iran’s flag until the revolution in 1979.

Pahlavi Dynasty

After the end of the rule of Qajars and with the establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty, the Lion and Sun symbol underwent modifications, reflecting a shift towards a more nationalistic interpretation. The Islamic component of monarchy was de-emphasized, aligning more closely with pre-Islamic Iranian history. This period also saw the lion and sun attributed to ancient antiquity by European visitors, prompting a nationalistic interpretation by Mohammad Shah Qajar in the mid-19th century.

The symbol’s Islamic aspects were downplayed, emphasizing its connection to Iran’s pre-Islamic glory and national identity.

The Legacy of Lion & Sun: A Symbol Beyond Revolutions

Despite its formal status ending with the 1979 revolution, the Lion and the Sun continues to resonate deeply within the Iranian psyche. This legacy transcends political changes, remaining a potent symbol of Iran’s rich historical tapestry and a source of national pride. Today, it finds expression in cultural, artistic, and historical contexts, signifying not just a bygone era but a continuous narrative of Persian identity and heritage.

After coming to power, Ruhollah Khomeini who was now the leader of Iran, gave a 10-day ultimatum to all government branches to remove what he called “a cursed sign” from all of their emblems, paperwork and offices.

Despite its formal status ending with the 1979 revolution, the Lion and the Sun continues to resonate deeply within the Iranian psyche. The Lion and Sun symbol has been adopted by various opposition groups against the Islamic Republic government. It continues to embody ancient and modern Iranian traditions, signifying a rich historical and cultural legacy. This emblem, deeply rooted in Iran’s past, now represents resistance and the struggle for an alternative vision of Iran.

If you like to hear more about the events mentioned in this post, listen to our podcast. In Lion and the Sun, we travel back to the Qajar dynasty and find our way through the events that have shaped Iran’s history.

You can listen to us on all podcast apps including Apple and Spotify.

4 Responses

Dear Sir/Madam:

I enjoyed reading your paper about Iran’s tricolour flag, featuring the Lion and Sun emblem. It was fascinating to learn about the flag’s historical significance, which traces its roots back to the faith of Mithraism. In the 12th century, the Seljuks Dynasty used the Lion and Sun as symbols to mediate between Shia and Sunni sects.

You mentioned that Khomeini issued a 10-day ultimatum for all government branches to remove what he called “a cursed sign.” However, Khomeini did not use the term “cursed sign”; he used the word “taghoot,” which means “rebellion.”

Thank you,

Yours sincerely

Peyman Adl Dousti Hagh

Thank you Peyman for adding that context. We’ll update the article with it.