This is the transcript for Book One, episode 1 of The Lion and the Sun podcast. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

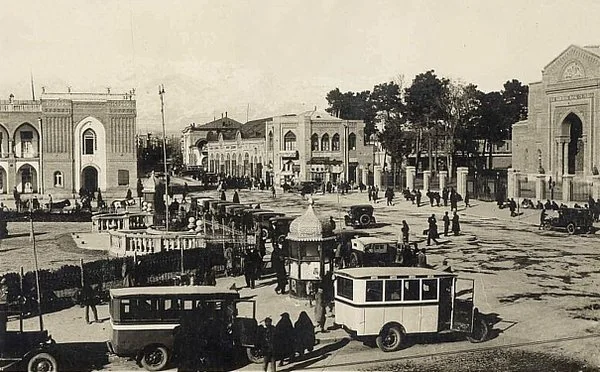

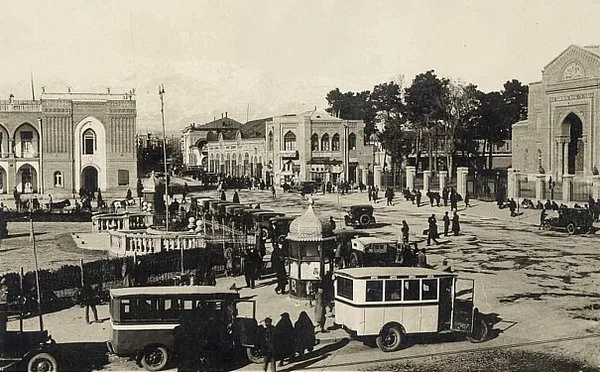

Tehran’s winters were known for being harsh and cold. The city, located at the foot of the Alborz mountain range, was often blanketed in snow and temperatures would frequently drop below freezing. Despite being the capital of Persia for more than a century, by all standards, Tehran was still an underdeveloped city. With ancient brick houses, dirt roads, and a lack of electricity in most of its areas.

The city had recently undergone a period of modernization and westernization, and this was reflected in its design as well; with a city citadel, civilian quarters and a marketplace for people to do business in. None of these were up to the 20th century standards, however. The capital of Persia seemed like a city lost in time and locked in an ancient era long gone.

It was what many considered a work in progress.

For Reza Khan, this barren capital of the Persian empire was filled with potential. Detached from the alliances of the north and south, far from foreign hands and prime for progress, the city was ready to be modernized. The only thing standing between the city and its rebirth was the people who controlled it.

An ancient monarchy on the brink of collapse, gangs devouring the neighbourhoods and their people, and corruption at every council and office. None of this was going to stop Reza, though.

He was a man with a plan

In Persia, the end of winter marks the start of a new year, which is celebrated with the traditional Persian festival of Nowruz, or “New Day.” This celebration marks the moment when the sun crosses the celestial equator, signalling the full passage of the Earth in its orbit around the sun and the official start of spring. Nowruz is a time for new beginnings, for coming together with loved ones, and for embracing change.

And on 1924, the biggest of these transformations was right around the corner …

Reza Khan was an agent of change. He always prided himself in being able to get things done, despite the uncertainty and the hurdles, he knew what he was capable of and was ready to carry the weight of the empire on its shoulders. He was ready to bring Persia into the new age.

Tehran’s winters were known for being harsh and cold, but the dream of spring always pushed people forward. And in 1924, the dream was bigger than ever. The land of Persia was ready to get rid of its monarchy. It was about to welcome democracy and join the free world.

Hello,

My name is Oriana and you’re listening to The Lion and the Sun.

The fight for Iran’s freedom goes back a long long time ago. Centuries before where we stand, many years before the winter of 1924, and decades before the rise of Reza Khan.

The unofficial start of Iran’s journey toward democracy dates back to the late 19th century when all Iranians, rich and poor came together to stand for what they loved most in the world.

Their right to smoke tobacco as they wished.

Qajar dynasty’s rule in Persia

In the late 19th century, Iran was controlled by the Qajar dynasty. Qajars were a Turkic tribe who ruled over northern parts of Persia, near the Caspian Sea. After a series of civil wars, this tribe came to power in 1789 and despite their powerful founder, Mohammad Khan, and their initial success in controlling the vast Persian empire, they slowly regressed and with each new king, they sank lower into inaptitude and powerlessness. They lacked a proper vision for the country and their desires never went further than luxurious feasts and lavish celebrations.

This absence of determination opened up Iran to become a pawn in the game of its powerful neighbours on the northern and southern sides.

In the north and through the Caspian Sea, Persia was neighboured by the empire of Russia. During the early 19th century and after a series of Russo-Persian wars, Qajars were forced to secede areas of their territory including modern-day Georgia, Azerbaijan, and later Armenia to the Russians through the disastrous Gulistan and Turkmenchay treaty. These treaties shrunk Persia’s vast presence in Asia and increased Russia’s influence in the country. Russia even formed the Persian Cossack Brigade in 1879 modeled after the Caucasian Cossack regiments of the Imperial Russian army which would play an integral role in Persia’s future. But that’s a story for another time.

In the South, it was a different story. Through the southeast part of its border, Persia was neighbor to India. United Kingdom’s newest and most prized possession and thus it was the perfect and most convenient land route to getting there.

As the Qajar’s inability to rule Iran with firm hands and strength became obvious to the global world, the Britains began to see Iran as a tantalizing and difficult-to-resist target for more influence in the region.

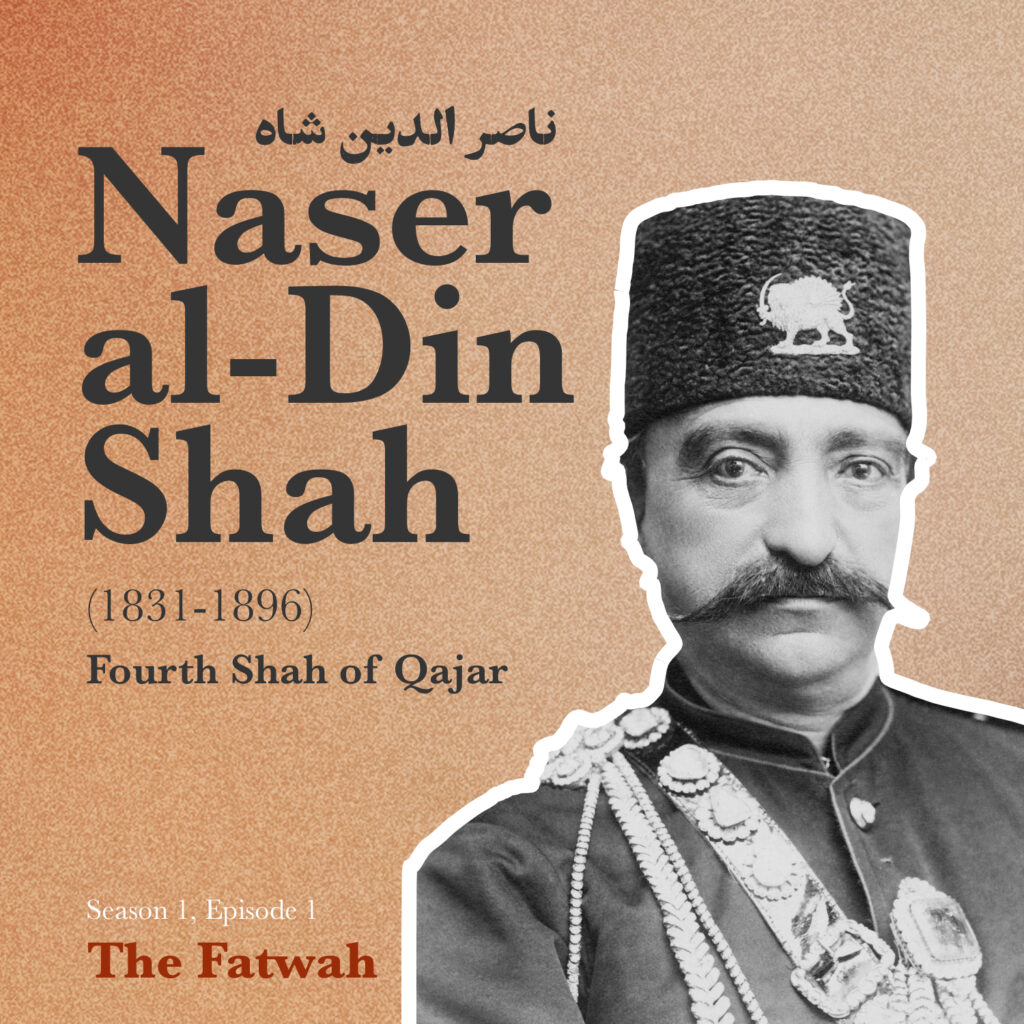

In the 1890s, Iran was ruled by King Nasir al-din or Nasir al-din Shah. The fourth ruler in the Qajar dynasty who ascended to the throne in 1851. By all measures, Nasir al-din Shah was a modern king. After traveling to Europe he became obsessed with the Western way of life and technology. He brought photography and telegraphs back to Persia and helped create the first Iranian University called “Dar-Al-Fonun”. But just like all other Qajar kings before, his tendency for authoritarian rule outweighed the reforms he brought to the nation. Nasir al-din shah called himself the shah of shahs and the asylum of the universe and anyone who dared oppose his divine rule was either shot or imprisoned for life.

Reuters concessions: How Qajars sold Iran’s resources

One of Nasir al-din Shah’s more controversial reforms was to sell Persia’s resources to foreign companies and individuals. The idea was that Persia could use the technology and capabilities of foreigners in exchange for sharing the profit with them; but in reality, things proved a little bit more complicated and the sharing of profits went “a little” too far!

In 1872, Baron Julius de Reuter, a German-born British entrepreneur who was a pioneer in news reporting and the founder of Reuter’s news agency signed a contract with Nasir al-din Shah. This contract gave him complete control over Persian roads, telegraphs, mills, factories, forests and extraction of any and all resources in exchange for its full profit for 5 years and 60% of net revenues for the two decades after. One could argue that this was the most complete package ever granted from a country to a foreigner in the history of any nation. Even the countries in the British Empire’s commonwealth didn’t give this much to their imperialist ruler. One fell swoop and Reuter was effectively the king regent of Persia.

This broad concession was met with anger across all spectrums. The Russians were crossed that with this agreement, they would lose all control and influence in northern parts of Iran. Iranians were enraged that their country was now fully under the control of the British, the Muslim community was worried about the Jewish background of Reuter and his satanic plans for diminishing the influence of Islam in the country and finally, the British officials were furious that they were excluded from this lucrative deal.

All of this led to a series of unrest amongst Iranians headed by Mulla Ali Kani, a religious figure. People blamed Mirza Hussein, the grand vizier of Nasir-al-din Shah as the mastermind of this economic coup and demanded his resignation. Nasir al-din Shah who had just returned from his lavish European trip was surprised by people’s reaction. His advisors told him that keeping His grand vizier would lead to civil unrest so he had to let Mirza Hossein resign and with pressure building up both from within and outside, he had no choice but to revoke the Reuters concession.

After the Reuter’s saga, one thing became clear. If Nasir al-din Shah was going to give away the rights of his country to foreigners, he had to be more sneaky about it and do it in smaller increments. In the next few years, the House of Qajar gave three smaller concessions to the British consortiums. The mineral prospecting rights, the right to establish banks, and the right to commerce in the Karun, Iran’s bigger rive. While giving these rights, Nasir al-din Shah also gave away the exclusive right to Iran’s Caviar fisheries to Russians to keep them from becoming angry with the British.

These concessions were made in the name of reform, but the real reason behind Nasir al-din Shah’s eagerness for foreign influence was the court’s overspending habits that left the country broke and in debt. Iran was a big borrower from British and Russian banks and none of these concessions were making an impactful dent in Iran’s growing debt crisis.

Tobacco concessions: Crossing the red line

Very soon, Iran’s monarchy decided to add another industry to the ever-growing list of their offerings to foreign powers. On March 20th, 1890, the Qajar court sold the Iranian tobacco industry to the British for a total sum of 15,000 pounds, equal to 1.8 million pounds in today’s value.

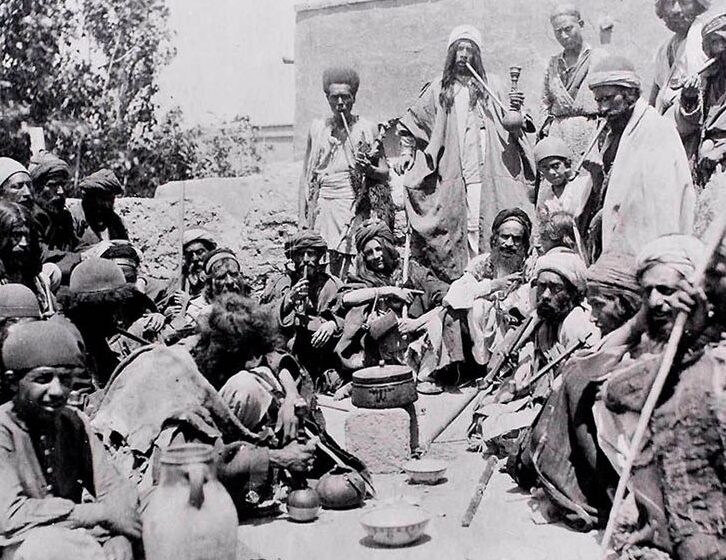

Most people agree that it was the Ottoman Empire that introduced tobacco to the Persians. In the 17th century, tobacco became an integral part of everyday Persia, so much so that Iranians began planting it in their fields and by the late 19th century, it became one of Persia’s biggest exports. So it was only natural for Nasir al-din shah to put it up for sale during his third trip to Europe; when he was in desperate need of money.

The buyer of Iran’s tobacco industry was Major G. F. Talbot who then managed to sell it to the imperial tobacco corporation of Persia, a shell company that he was the majority shareholder of it. Talbot intended to purchase the tobacco directly from the farmers with a fixed price set by the company and then not only distribute it within the Persian populous itself but also export it internationally.

The first group to express their anger with Nasir-al-din Shah’s decision was the Russians. Some of the Russians were in the business of farming tobacco in the northern regions of Iran and they weren’t ready to hand out all their profit to their British rivals. They also believed that the tobacco concession was against the Turkmenchay treaty mentioned earlier. But despite the Russian pushback, Nasir-al-din Shah was in desperate need of money and nothing was stopping him from finalizing the deal with Major Talbot.

In February 1981 Talbot traveled to Iran to appoint Julius Ornstein as the director of the Tobacco Regie and afterward, Shah officially announced the deal to Persian farmers and workers.

During this period, over 200,000 Persians were in the business of growing and selling tobacco, which meant almost 2% of the population was directly impacted by Nasir al-din Shah’s tobacco concessions. They could no longer set their own price, they could only sell their tobacco to one buyer and that buyer would dictate the terms of the purchase.

People’s response: Iran’s tobacco protests

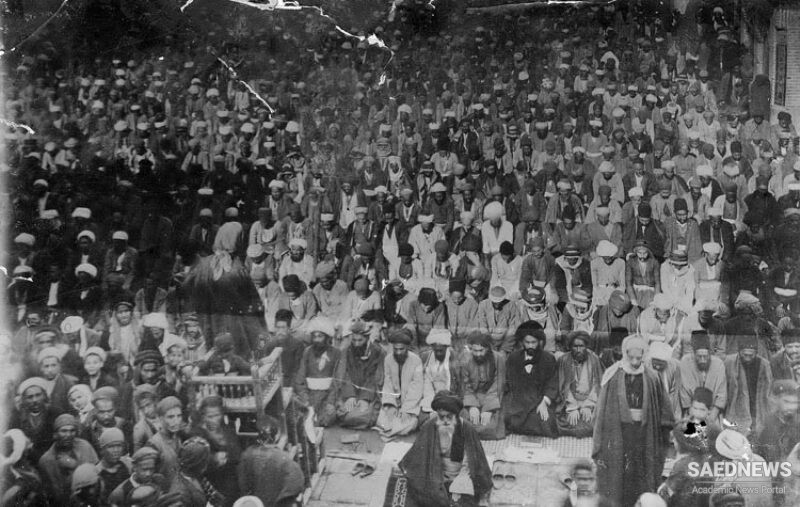

After the announcement, Persian merchants began organizing protests across the bazaars of Shiraz but soon and with the help of religious clergies, other cities began to join as well.

The involvement of religious leaders in the tobacco fights might seem a bit odd and out of place, but given the historical and geographical context of previous similar events, it only seemed natural for them to be worried about the concessions.

Ever since the Safavid empire, Persia’s official religion has been Shia. A branch of Islam where the clergy or the “Ulema” have always been very active in the social and political landscape. In Persia, the clergy ran the religious schools and were trusted as arbiters and judges, and their stamp was the seal of approval for notarizing any document. Religion was deeply intertwined with the lives of people and the words of the religious leaders carried a lot of weight.

After the announcement of the tobacco deal, Talbot and Ornstein began bringing British people to Persia to help them control and manage the tobacco market. Thousands of foreigners came to Iran as official workers of the Imperial Tobacco Corporation of Persia and with them, the British lifestyle also found itself within Persian borders. They were building bars, setting up cafes for gambling, and most dangerous of all, they were building churches for their religion. A religion that was different than Islam and in their minds, posed a threat to its supremacy in the region.

The Shia clergies were afraid that with Christianity on the rise, their influence within the community would diminish, and soon, the independence of the country would be in danger.

And they weren’t completely wrong!

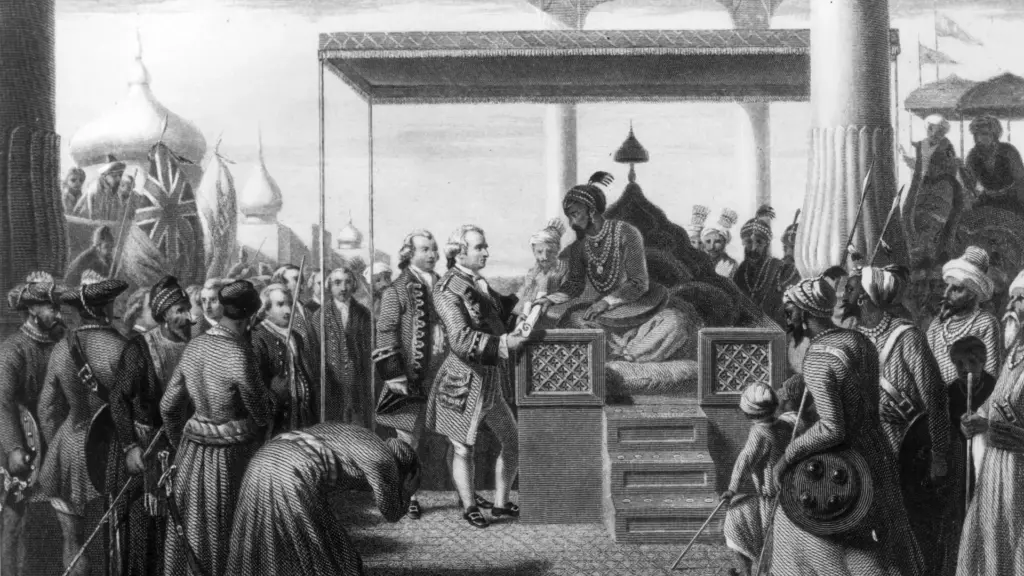

In the 1600s, another British entity called “East India Company” established itself within India to create a spice trade between the Indian peninsula and the British Empire. Gradually the East India company grew its presence within India, became a monopoly within the regions, gained ownership of many parts of the land, and in the end, turned India into a British colony.

Persia was also beginning to follow the same trajectory. A foreign country tightening its grip on a profitable industry and increasing its presence within the country. If people didn’t fight, soon, the whole country might’ve become just another colonial part of the British empire.

One of the cities with the harshest rebuttals to the new tobacco policy was Isfahan. A central city close to Tehran, Isfahan was once the jewel of the Persian empire The city was home to many impressive buildings and monuments and its streets were alive with the sounds of traditional music and the aroma of delicious food. Isfahan was a center for arts and crafts, with skilled artisans producing everything from delicate pottery to intricate metalwork. The city played an important role in Persia’s political progress and despite its decline during the Qajar era, still held a critical place in the monarchy.

In Isfahan, the clergy and people had a more intertwined relationship so the religious leaders managed to put a ban on tobacco and called the workers of the new tobacco regie “najes”. A religious term referring to something that is unclean, cannot be cleaned and turns everything it touches unclean as well. The people of Isfahan embraced this ruling and instead of selling their tobacco to the foreigners, decided to burn their crops. The ruler of Isfahan tried negotiating with the religious leaders but after the eventual failure of the talks, banished them out of the city.

The Fatwah: Banning tobacco

While the other cities were taking a more hostile approach to the issue, in Tehran Mirza Hassan Ashtiani, another reputable clergy took the issue directly to the shah and his grand-vizir, talking about further escalation if the monarchy went ahead with the transition of tobacco rights to the foreigners. Despite the warnings, the king maintained that his decision was beneficial to the country and the British would do good for Persia. With the Shah’s disregard for the voice of the people, the tobacco protests spread to other cities such as Tehran, and this news found its way to Iraq and Mirza Shirazi.

Seyed Mohammad Hassan Hosseini Shirazi or simply Mirza Shirazi was an Iranian-Iraqi Shia marja.

Marja with the literal meaning of “source to follow” is the highest title a clergy can obtain in Shia Islam. A person who can make legal and theological decisions regarding the rules of Islam and his word constitutes the word of god. When a Marja issues a ruling, that ruling is universal to all his followers and failure to comply with it counts as a sin and is forbidden.

Miza Shirazi was a Marja who lived in the city of Najaf in Iraq. He started his religious studies when he was four and after excelling in the Islamic school of Isfahan and then Shiraz, had managed to travel to Iraq to expand his knowledge of theology; where he stayed and practiced his religion.

In Najaf, he was made aware of the sale of tobacco rights. In 1890, a Persian newspaper from the Ottoman Empire compared Talbot’s deal with Iran to their own tobacco deal and found out that Talbot’s was paying less than half to Iranian farmers and taking advantage of the weak economic standings of Nasir-al-din Shah.

Upon reading this, he issued a telegraph to the king himself where he explained how the deal was against the word of god in the Quran, in contrast with the actions of the prophet and a clear danger to Persia’s sovereignty. He asked the king to reconsider his decision and cancel the deal before it was too late but Nasir-al-din Shah, adamant in his actions and desperate for cashflow, ignored the telegraph and instead, sent Persia’s ambassador to Baghdad to visit Shirazi and to make things clear for the clergy.

The ambassador met with Shirazi and explained how positive cooperation with the European countries is a necessity of the modern age and how the country’s taxes weren’t enough to fund the country’s expenditures. Shirazi wasn’t convinced. He simply said that if the monarchy doesn’t solve the issue, he will take care of it on behalf of god and ended the meeting.

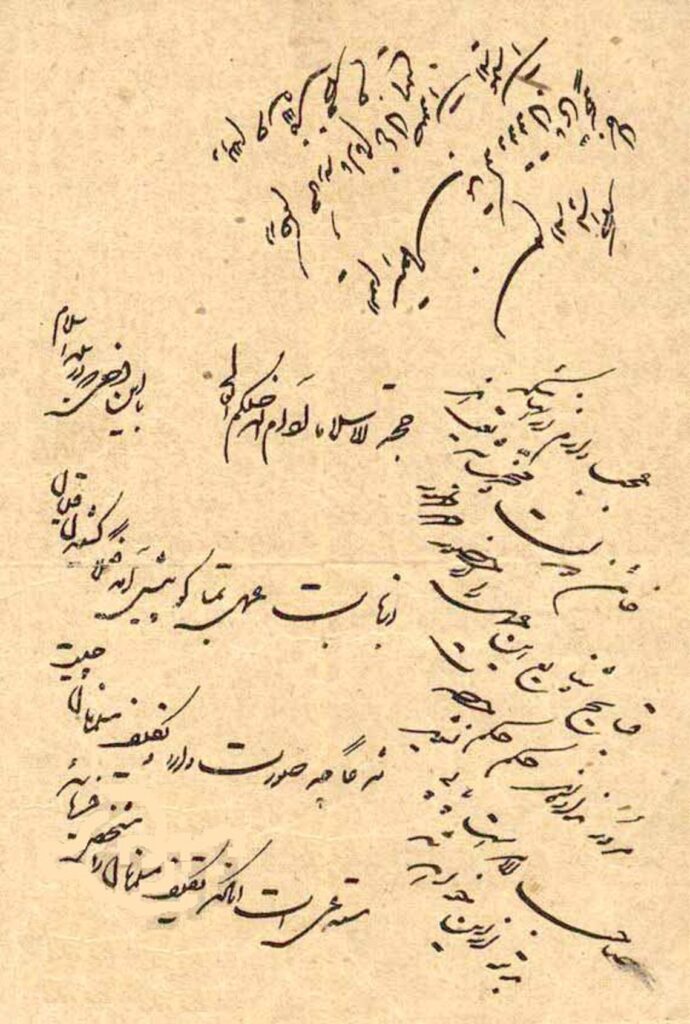

On December 1891, Ashtiani, the famous clergy of the capital announced that Mirza Shirazi had issued a fatwah against the usage of tobacco.

What is a Fatwah?

The followers of Shia believe that 700 years ago and before the death of their prophet, Muhammad had appointed his son-in-law and cousin, Ali as his successor. The imam that would lead people when he’s gone. However, after his death, many of Mohammed’s disciples, decided that Ali’s appointment was too vague to be taken literally so they named someone else as his successor. So another ally of Mohammad, Abu Bakr, a powerful and very rich Muslim in the Arabian peninsula was chosen as Muhammad’s successor. Thus began the drift between the Shia Muslims and the Sunni Muslims.

In Shia Islam, there have been 11 imams after Ali, all descendants of Muhammad, who are known as “Ahle beyt.” The 12th imam, known as the “Mahdi” or the imam of our age, went into hiding to protect himself, and it is believed that he will one day return to bring the true rule of Islam to the world. In the absence of the 12th imam, religious leaders known as Marja provide guidance to the community by issuing fatwahs.

Fatwahs are legal religious rulings that help to interpret and apply Islamic teachings in a modern context and in the absence of the 12th Imam.

Ban on tobacco: the ultimate response

When it came to the tobacco protests, Mirza Shirazi was taking a new approach to his religious rulings. He was weaponizing religion to fight for a social cause and using fatwahs to stand against the monarchy.

His stance meant that anyone who would sell tobacco to the British or even smoke it was defying the 12th imam and for Shiite Muslims, this was a big offence. The fatwah first came into the possession of Hassan Ashtiani, the clergy in Tehran who had first tried to reason with the Qajars. When the monarchy found out about the ruling, they sent their police to make sure the fatwah won’t get distributed to people, but within the first day, tens of thousands of copies were made and distributed within Tehran and sent to other cities.

Within 24 hours, Persians stopped smoking tobacco altogether. The hookas were absent from the cafes, cigarettes ceased to exist in the streets and anyone who packed a smoke was treated with disgust and shunned from social circles. Overnight, tobacco went from a sought-after substance to a deadly poison everybody avoided! The ban on this leafy substance even reached the Qajar court and Nasir-al-din Shah’s harem.

Nasir-al-Din Shah wasn’t a man of the people. He wasn’t aware of the thoughts and feelings of the common folk. But once he saw that all his many wives were refusing to use hooka and smoke tobacco, he knew things were serious.

His first strategy was to cast doubt on the authenticity of the fatwah. He tried to smear the text as a fake and urged people not to get fooled by the tricksters. He even found a scapegoat to blame for the forgery and banished him outside of the capital. But ultimately the plan didn’t work out. People were just too trusting of their religious leaders who copied the fatwah and distributed it in mosques and other common places.

Plan B involved bribing religious leaders to stand against the fatwah. The Qajari court went to Mirza Hassan Ashtiani, the most well-known clergy of the capital which was the main distributor of the infamous order, and offered him all the concessions he would want. In return, they asked him to issue a contradicting fatwah allowing the use of tobacco once more. Naturally, he refused. The clergies all respected Mirza Shirazi too much and weren’t going to directly oppose the word of their highest-ranking peer. Ashtiani who feared the court’s pressure on him would only increase decided to leave Tehran altogether and continue his work somewhere else.

Aftermath of the tobacco protests

Finally, 55 days after the issue of Shirazi’s fatwah and on January 6th, 1892, Shah had no choice but to dissolve the tobacco concession. In a letter written to his grand-vizir, he asked him to notify the people and the clergy of the dissolution.

Due to the cancellation, Iran had to pay 500,000 pounds to Talbot for damages and an additional 139,000 to cover the costs of the infrastructure brought to the country. The tobacco incident was a massive failure for the government and it sunk Persia further into debt and crisis. Not only did it not help ameliorate the financial troubles of the Qajar court, but the additional costs bankrupted the country even more.

Iran was in so much debt that Nasir-al-din shah had to take a loan from the British government to pay off the debt he owed to the British.Shah

After Shah’s decision, Mirza Shirazi rescinded his fatwah, and the use of tobacco was once again allowed in society. The tobacco movement gave Persians and the clergy a strong momentum for social and political reforms. They had the leverage to expand their demands on the court, implement big changes, and bring real reform to the country. But this is where Qajar’s negotiation with the clergy paid off.

Mirza Hassan Shirazi, realizing the power of his word; was ready to take the fight to the next level and demand further compromise from the monarchy. He wanted to revoke other concessions given to foreigners and reduce the influence of the British and the Russians, but Ashtiani asked him personally to hold off on further demands and to be content of the change they were able to accomplish. That very same year, a new and extended list of clergies was added to Qajar’s payroll, and any further attempts for social justice were swept under their religious and powerful rug.

Only a few months after the whole fiasco, Nasir al-din Shah sold the tobacco rights to another foreign company in France. However this time he was smart enough to consult with the clergies first and to give the selling rights within the country to Persians instead. These small tweaks were enough to keep everyone happy and prevent another political crisis for the already fragile Qajar dynasty.

Despite its limitations, setbacks, and regressions, the tobacco movement was a critical victory for the Persians with many important lessons. It proved the importance of a populist cause to inspire everyday folks, it showed the power they possessed against the monarchy and it demonstrated the impact of religion in the fight for justice.

The tobacco protests were narrow in scope and didn’t result in any massive changes or a political reconstruction, but the movement itself became a symbol. A sign of hope that through action and devotion, anything was possible. By finding a common cause that everyone could relate to, the issue of tobacco became a stepping stone to prepare Iranians for the bigger fights yet to come…

It was only natural that after taking back the rights to their tobacco, Iranian’s next goal would be to reach for democracy itself.

2 Responses