This is the transcript for Book One, episode 2 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: The Persian Awakening. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

May of 1896 was a special time in Persia.

As the Persian New Year passed, people shed their winter cloaks and embraced the luscious Middle Eastern spring. Nature had bestowed its blessings on the land. The earth was a canvas of natural wonders that radiated a renewed vibrance with every passing day. But this particular spring was unique for a whole lot of different reasons.

In May of 1896, the kingdom of Persia was preparing itself to celebrate the golden jubilee of it’s Shah. The 50-year rule of the Nasir-al-din Shah had been a consequential period for the region. He had tried to bring aspects of 19th-century modernity to the country but at the cost of losing many concessions to the Russian and British governments.

Yet, none of this was going to stop Nasir-al-Din from the majestic celebration of his 50-year tenure as Persia’s king and his overseeing of one the world’s greatest empires. At least that’s what he still believed.

In the following months, the government employees busily adorned official buildings with elegant decor. The streets and bazaars too were not forgotten, for city workers skillfully embellished them with alluring ornaments. Even in foreign lands, Iran’s ambassadors toiled to spread the word of the 50-year reign of their king. The world was to know that Persia shone as a beacon of grandeur and magnificence.

Before the official start of the celebration, Shah wanted to do his religious pilgrimage to the mosque of a descendant of Shia Imams, buried in a city close to Tehran.

The protocol for these types of visits was that the religious site would be closed to the public and the Shah and his entourage would have a private visit and pay their respects. But with the celebrations looming close, Iran’s Shah decided to do a public visit. Nasir-al-din wanted to be amongst his people. He wanted the nation to see how even after 50 years of ruling, Iran’s shah was still a down-to-earth Guy.

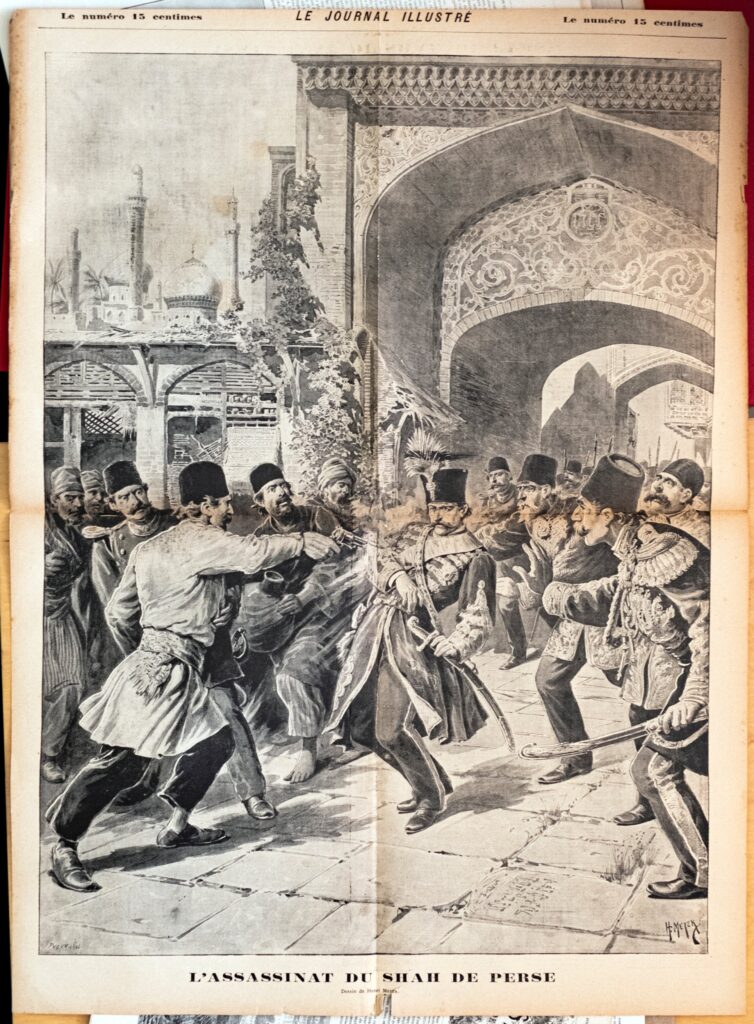

On Friday, May 1st, Nasir-al-din Shah entered the Abd-al-azeem mosque and started approaching the main shrine. But just as he was about to pay his respects and do his prayers, a man appeared in front of him, took out a gun from under his robe, and shot the Persian king right through the heart.

As Nasir-al-din Shah’s entourage rushed to find the person responsible, waves of people ran and scattered in panic. Amidst the pandemonium, blood flew on the mosque’s floor and the Qajar’s longest-reigning monarch lay dead on the ground.

Hello,

My name is Oriana and you’re listening to The Lion and The Sun.

The Shah’s Assassination

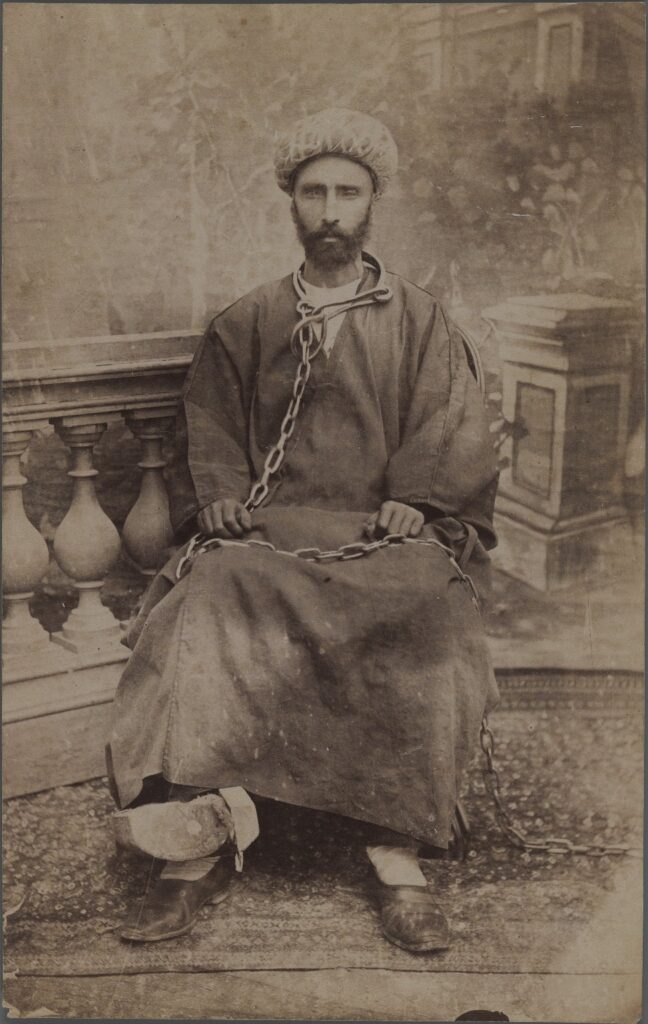

The person responsible for Nasir-Al-Din Shah’s assassination was Mirza Reza Kermani. Or as he was later known, Reza the king slayer. He wasn’t a political rival, an heir to the throne nor did he have a personal grudge against the king. He was a peasant who was constantly pressured by the local rulers of Tehran. A peasant frustrated with the living conditions of his country.

After the Tobacco protests, Nasir-Al-Din Shah had no choice but to revoke the tobacco concessions given to the British. This breach of contract led to Iran having to pay over 600,000 pounds to the Western Empire in damages. The Qajar dynasty didn’t have the funds necessary to pay the fine. So the king had to take out a loan from the Imperial Bank of Persia which was controlled by the British themselves.

During this time, the price of silver was also dropping in the global market. This led to the devaluation of Kran, Persia’s then currency. The devaluation caused inflation across the country and decreased the tax revenue of the government which in turn bankrupted the government.

Yet, despite the financial troubles, Nasir-al-din Shah wouldn’t budge on his luxurious lifestyle and his lavish trips across Europe. He believed that this travel was essential for familiarizing him and therefore Persia with the modern world. But in reality, the trips were incurring expensive costs that the government couldn’t afford; while the ordinary people suffered.

Facing these pressures and the constant abuse by the local rulers, Mirza Reza Kermani tried to submit a complaint against the people in charge and ask for leniency from the government. Instead, he was sent to prison for his discretions. In Prison, he developed a hate for the entire ruling class of the country. He thought by killing Nasir-al-din shah, he was taking out the root of this rotten tree. That the death of the king would result in the collapse of the monarchy. But the death of Nasir-al-din shah, only made things worse for the Iranians.

After the assassination, those close to the Shah tried to keep the news a secret. They took Nasir-al-din Shah’s body to Tehran and announced that he’s only been wounded after an attack on the mosque. Despite the precautions, people feared the worst and started looting the markets for bread and fruits. The ruler of Tehran announced martial law and with the help of the army kept control of the city. Uncertain of how long this forced calm would last, the Qajar court started the process of transferring power by announcing the death of the king to his heir, Mozafar Khan.

New King, Old Problems

Mozafar was the fifth son of Nasir-al-din Shah. However, the early death of the three eldest and the questionable heritage of the fourth child, made him the heir apparent to the Persian throne.

Mozaffar was content with the way things were being handled under the rule of his father. Therefore, he settled into the role of the king without much change and kept everything the way it was.

Mozafar-al-din Shah, just like his father, was a big fan of travelling and wanted to visit Europe. But with the court on the brink of bankruptcy, he didn’t have the funds to do so. That’s why in the march of 1900, he turned to the Russian empire and asked for a million-pound loan to finance his voyage into the west. Two years later, he asked for another two million for his second trip.

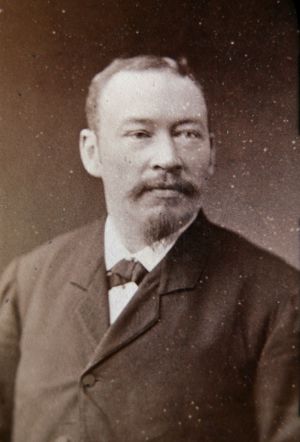

To make up for this deficit, The king hired Joseph Naus from Belgium to head Iran’s Customs and Tariffs department. Naus was successful in raising Iran’s customs revenue from 200 thousand pounds in 1898 to 600 thousand pounds in 1904. But the income was nothing compared to the debt Persia owed to the foreign governments.

Debt wasn’t the only issue Qajars had to worry about. In 1904, after a surprise attack on the Russian Pacific Fleet at Port Arthur, Russia entered into war with Japan. Thus the trade routes on the northern side of Iran were brought to a halt. This led to a significant increase in food prices with a 33% increase in sugar prices and a 90% increase in wheat.

And if the economic crisis wasn’t bad enough, in 1905, Persia and its capital city of Tehran, were hit with a severe case of Cholera. With people dying by the thousands and most escaping the affected cities for the safety of themselves and their families.

All of this pushed Persia towards its biggest societal change in centuries.

Start of the Persian Awakening

In the early 19th century, with the expansion of trade between Persia and the world, wealthy and elite Persians started visiting Europe. They studied there and were influenced by the way things were done in the West. They witnessed the parliament system in place in the United Kingdom. How educational institutions and universities cultivated knowledge. And how newspapers made sure that the public was aware of the latest developments in their countries.

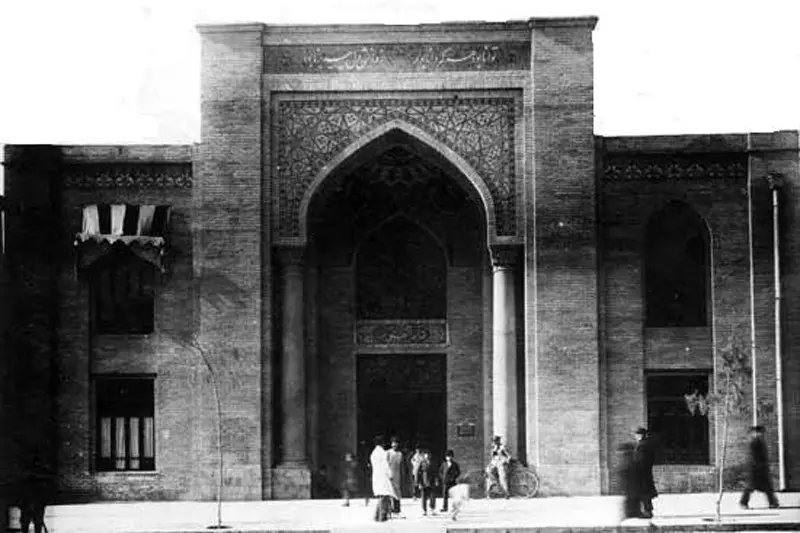

This led to the creation of Persia’s first university called “Dar-Al-Fonoon” in 1851 and the publication of the first Iranian newspaper in 1837. These significant milestones marked what many historians now refer to as “The Persian Awakening.“

The Persians saw how the great powers were changing. The British had their own parliament since the 15th century. The French went through their revolution in the 18th century. Even the Ottomans established their very limited General Assembly in 1876. The world was advancing in social and political aspects but their own country stagnated when it came to reforms and progression.

The Tobacco protest was the first instance where people came together to fight for a united cause. After its limited success, it was only a matter of time before they demanded something far more substantial from the monarchy that had taken them hostage for the past century.

On December 12th, 1905, the perfect opportunity presented itself!

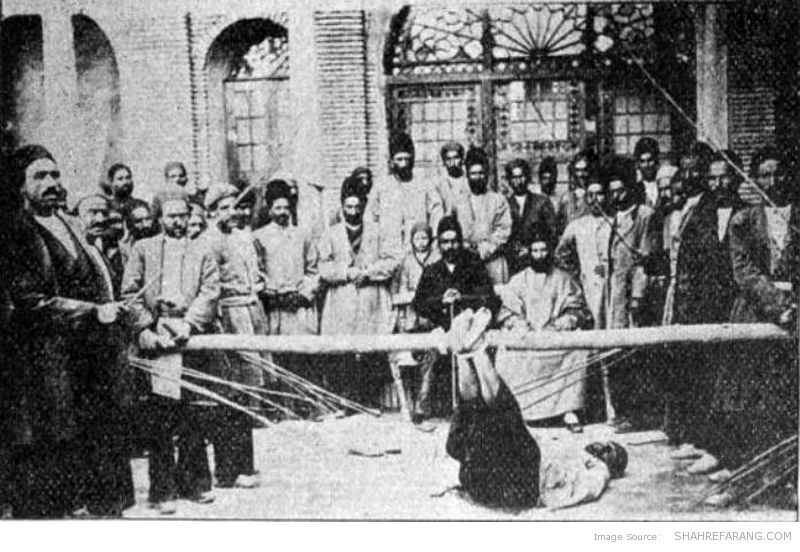

With the Russo-Japanese War hurting the trade and Iran’s mounting debt to Britain and Russia, inflation spread rapidly across the country. This led to a significant increase in the price of sugar, prompting the ruler of Tehran to lash out at two sugar merchants in the city for the crime of “price gouging.” The merchants were tied up to a pole and had their feet whipped as punishment.

This punishment was called “Falak” or “bastinado.” Falak was a common type of disciplining for the guilty people in old Persia. These merchants were two of the most well-known traders of the capital. One of them, age 79 had built three mosques in the city and even repaired the Bazaar out of his own pocket after some damages.

When the news of this act reached other merchants and people of Baazar, they got furious. They immediately shut down their stores and business the day after. The angry merchants went to the mosque where Nasir-Al-Din shah was assassinated and announced their strike. They were planning on staying there until their three demands were met:

- The dismissal of Tehran’s Ruler

- The firing of Joseph Naus as the head of customs

- The establishment of a House of Justice.

Initially, the government stood against the changes. They even tried to break the strikes and force the merchants back to work. But Mohammad Ali Mirza, the potential heir to Mozaffar who had a beef with his father’s grand-vizir, wanted to establish his place as the true heir. So he secretly supported these protests and with his help, the Qajar court finally gave in to the three demands.

The merchants returned to the capital to roaring chants of “Long live the people of Iran.” Afterwards, Mozaffar-al-din Shah dismissed the ruler of Tehran. The king also ordered the establishment of the “house of justice”, but the firing of Joseph Naus was postponed to a later date.

One year after the protests, Mozaffar was still unable to cut ties with Naus. Iran’s customs revenue was too dependent on him and the country was still under a lot of debt. Furthermore, despite his royal decree, there had been no development in the proposed “House of Justice.” People were running out of patience again.

Significance of Muharram for Muslims

The religious month of Muharram held special significance for Shia Muslims. It marks the anniversary of the Battle of Karbala, a tragic event that occurred in 680 AC. This battle was fought between the supporters of the Um Sayyed Caliph Yazid and the followers of Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad.

As mentioned in the previous episode, after the death of the prophet, there had been a divide between those who followed Ali and those who pledged to Abu Bakr. Eventually, Ali accepted Abu Bakr as the caliphate and retired from public life.

Following Abu Bakr’s death, Umar and Usman were elected as his successors. But Usman’s reign was cut short when he was assassinated in 656. This led to a period of political instability, with various factions vying for control of the caliphate. The political instability eventually calmed when the Muslim community finally granted Ali the opportunity to become the fourth caliphate of the Islamic state.

Ali’s election as the caliphate was a controversial ordeal. The people close to Usman, the previous caliphate, wanted Ali to prosecute those responsible for his assassination. However after his refusal, a Muslim civil war started between the two branches. With Muawiah, one of Usman’s closest allies leading a rebellion against Ali’s state.

In 660, Ali was assassinated and his followers picked his firstborn, Hassan as his replacement. Hassan, wanting to prevent further wars within the Muslim community, rested his claims to the caliphate and signed a peace treaty with Muawiah. In the treaty, it was agreed that after Muawiah, the Muslims will have a chance to elect another member as their caliphate and that Muawiah would stop persecuting Ali’s descendants and supporters.

Initially, Muawiah agreed with the treaty but years later, he selected his son, Yazid as his heir and the next caliphate of the Islamic state, contradicting his agreement with Hassan.

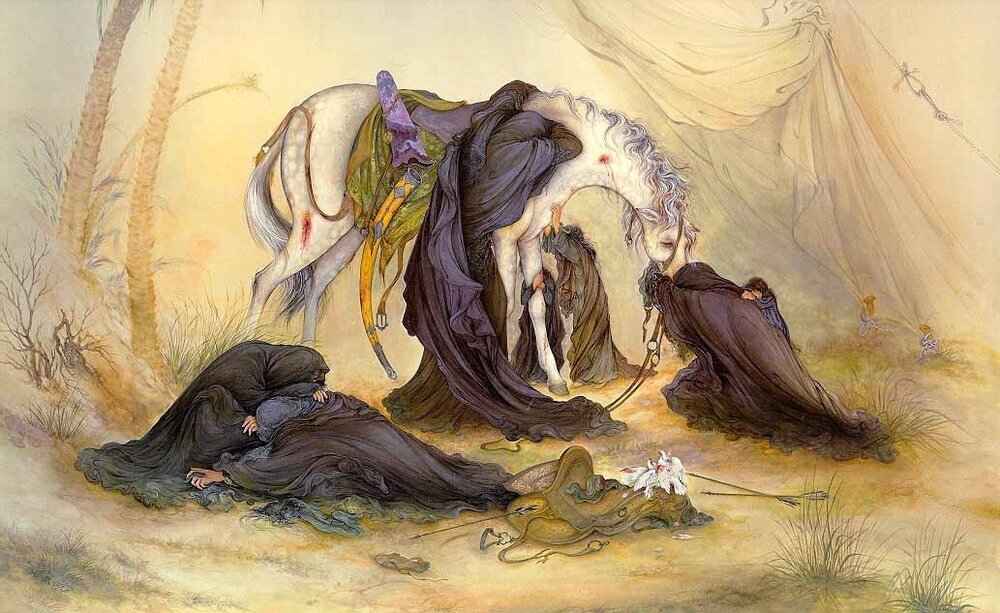

After Hassan’s passing in 670, Hossein – his younger brother – picked up the mantle. In 680, Yazid who had inherited the caliphate from his father sent him a letter asking for his allegiance. Hossein refused this request. ّn the month of Muharram 681, Hossein, along with his family and followers, went on a journey to Kufa, Iraq, to claim his right to the Caliphate.

On the way, Hossein and his followers camped in the Karbala region and there, they faced the Army of Yazid. Hossein and his followers, who numbered around 72, were surrounded and outnumbered by the Yazid army of around 4,000 men. They were denied water and food and were eventually killed in a battle that lasted for several days.

The Battle of Karbala is considered a turning point in the history of Islam. It led to the split of the Muslim community into the majority Sunni and the minority Shia sects. Shia Muslims, in particular, commemorate the event of Karbala during the month of Muharram. They do so through mourning rituals, such as self-flagellation, speeches, and processions.

For Shites, Hossein is a martyr and a symbol of resistance against oppression and injustice.

His sacrifice is seen as an important reminder of the importance of standing up for what is right and the sacrifice of those who fought for the cause of justice. That’s why the month of Muharram is usually associated with political activism and standing up against tyranny.

People vs. House Qajar

In July 1906, during Muharram, the Qajar government arrested a preacher who had been delivering speeches against the ruling dynasty. After the arrest, a group of religious students demanded his release. This protest turned violent, resulting in the death of one of the students.

In the aftermath, the other students took their bloodstained clothing and displayed it in the streets, further inflaming public anger. The following day, people from various sectors of society, including bazaar merchants, clergy members, and other businesses, gathered for the funeral and burial of the deceased. But the government fearing the large crowd, intertwined and the head of Tehran’s security ordered his troops to start shooting at the mourners.

There aren’t any exact numbers but according to different resources between 23 to 100 people died that day and hundreds of people were wounded.

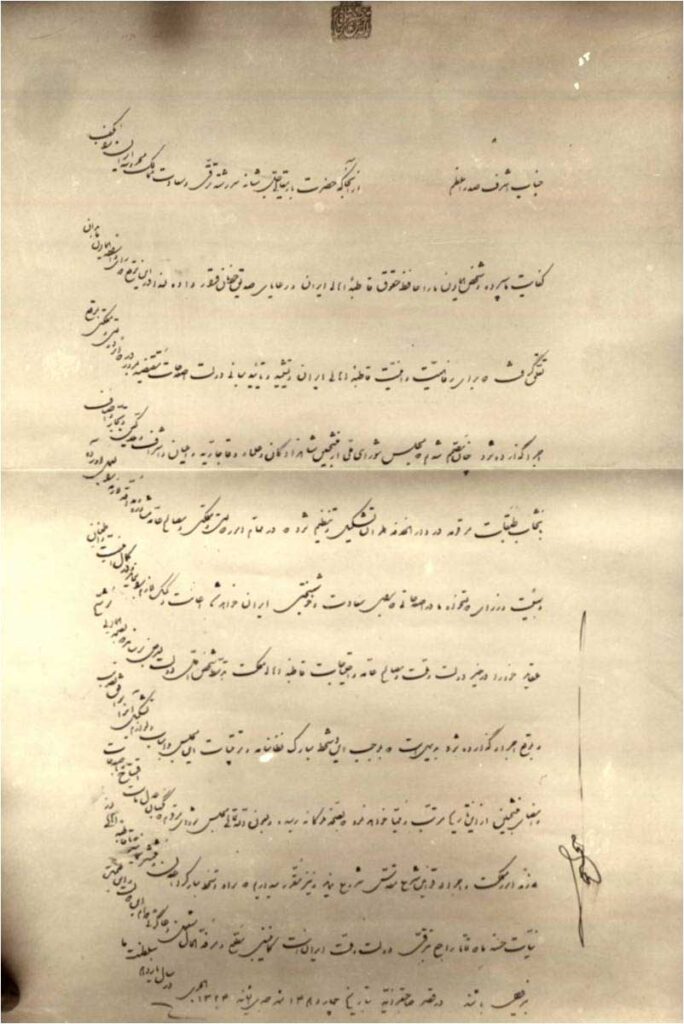

This led to the third wave of protests against the monarchy. The prominent religious figures of the capital, including Seyyed Abdullah Behbahani, in an act of defiance and protest, left the city and went to Qom. They wrote a harsh criticism to the shah, announcing that they would not return unless he conformed to their demands.

The British Embassy Comes to the Rescue

Behbahani was a prominent Shia clergy during his time and a significant figure in Iranian politics. One of his first notable acts was rejecting Shirazi’s fatwah that banned tobacco use. Behbahani believed that the agreement with the British would benefit Iran. He made a conscious effort to display his disdain for the fatwah and tobacco ban. This move caused him to lose popularity among the masses. However, over the years, he emerged as one of the leading figures in the fight against Mozaffar ad-Din Shah’s regime.

Behbahani’s involvement in the anti-monarchy movement dates back to 1905. When a photograph of Joseph Naus at a masquerade ball dressed as a religious clergyman was leaked. Behbahani was incensed by this act and used the picture in his religious sermons, calling for Naus’s dismissal. When Mozaffar ad-Din Shah refused to take action, Behbahani became a fierce opponent of his court.

Although he did not necessarily agree with all of the demands of the protestors, and in some cases, he opposed their beliefs as he saw them as against the values of Islam, he became one of the most prominent figures in the fight against the power of the court during this period.

After earning a lot of goodwill from his support of the tobacco deal, Behbahani wrote a letter to the British ambassador requesting that the people be allowed to use the embassy as a sanctuary for their strikes and protests. The British government initially rejected the request, but after a second request was made by the clergy and other prominent figures, the embassy finally allowed the protestors to take shelter in the outside vicinity of their state on July 19th, 1906.

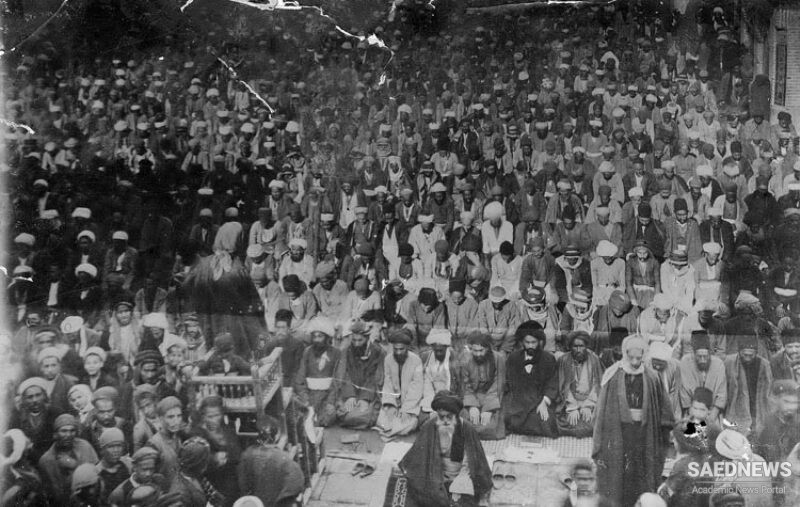

The next day, over 50 people came to the embassy and sat there in protest. The day after, even more people showed and each day the number of protestors increased substantially. Soon a community was shaped within the walls of the embassy with numbers reaching above 14 thousand.

They would hold talks and discussions about the European political systems. Learn about the constitutional governments across the world. They’d even discuss how Persia could benefit from having its own parliament, overseeing the orders of the Shah, and keeping him in check.

Ever since the revolution of 1688, the British people had put significant limitations on their monarchy and gave parliament more power in deciding the path for the country. This made their embassy a safe haven for the protestors. The British were in the same boat as them. They had the same ideals and they had fought for what the Persians were fighting for. Within the walls of the British embassy, the constitutional fighters felt more at home than in their own country.

For the British government, this was the perfect opportunity to gain back the trust of the Iranian people. They saw the shift toward centralized government in Persia as inevitable. By gaining the trust of the people they were setting themselves up for a victory over the Russians in the long run.

The organization of these protests and strikes was a massive undertaking. With camps set up all over the outdoor area of the embassy, each union having its designated space. The protests were managed by the heads of the unions, who allocated space to newcomers, implemented rules to maintain order and prevent chaos, and ensured that protest funds, donated by powerful merchants, were used efficiently. A mutual ground was established with pots full of stews and soups brewing. This way, the residents would not go hungry. Resources were also allocated to keep the protestors satisfied throughout the protests. It is worth noting, however, that during this period, women were prohibited from participating in these events. They were not even allowed inside the British embassy.

What happened during the summer of 1906 was truly magical. Iranian people, tired of the monarchy’s selfish rule and Persia’s declining economic conditions came together in this grand and extensive show of discontent. For three weeks, the protestors lived in the same camp. They ate together and talked about the most important issues that were on their minds. From this discourse, their demands went beyond anything they could ever dream of.

Dream of Democracy

By the end of June, Mozaffar-Ad-Din Shah, fearing the persisting strikes, gave up the fight and agreed to the original demands of the protestors once more. But these demands were no longer enough.

The British embassy protests, which took place between July 20th and August 11th, resulted in a significant shift in people’s demands. Instead of a vague “house of justice” with unclear functionality and minor reforms, the protestors sought a more substantial change – the establishment of a parliament where individuals from various fields of life could come together, discuss issues, and create laws that would benefit the common people. This assembly was to be called the Majles, and it became a crucial demand for those fighting against the monarchy. The protests represented a turning point in Iranian history, marking the beginning of a movement towards more democratic values and a departure from the traditional autocratic system.

Resistance was futile. Shah had no choice but to cave in.

On August 5th, 1906, Mozaffar ad-Din Shah gave out the order for the establishment of the National Consultative Assembly.

A committee consisting of politicians, nobles, merchants, and religious figures was formed to devise the general rules of the parliament and the election process of its members.

The parliament was to have 156 members, with 60 of them selected from Tehran and the rest from other regions of the country. The members of the parliament were to be selected from different classes of society with royals, nobility, shitte clergy, merchants, unions, and land owners each having their own seats. The parliament would start its work once the members from Tehran were selected and would gradually fill the other seats as other regions went through with their elections.

Finally, after months of talks, negotiations, and protests, on October 7th, 1906, the 1st National Consultative Assembly of Persia opened its doors and began its work.

Persia finally had a parliament of its own!

For Iranians, the parliament was just the beginning. Now that the working class had a voice of their own and had the power to implement change, they wanted to rewrite the constitution and limit the power of the Qajar court. But with a sick shah on his dying bed and an heir who was a fierce enemy of democracy, the opportunity for change was running out.

In the next episode of the lion and the Sun, we talk about the attempts to change the Persian constitution and how the successor to Mozzafar was bent on destroying the progress Iranians had made!

2 Responses

To introduce Iranians, you should use the word “Iran”, not “Persia”. This is not correct, please correct it! Because there are many tribes in Iran, “Persians” being one of them. For example, we are the Turks of South Azerbaijan and we live in Iran and have a population of 30,000,000 million

Thank you for your comment. You are absolutely correct. We’ve even addressed this topic in a blog post. The official renaming of the country occurred during Reza Shah’s reign. Before that, many nations referred to its people as Persians, which is why we use the term in our podcast. However, starting from season two and Reza Shah’s renaming, we will exclusively refer to the country as Iran and its people as Iranians.