This is the transcript for Book One, episode 3 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: The Tale of Two Shahs. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

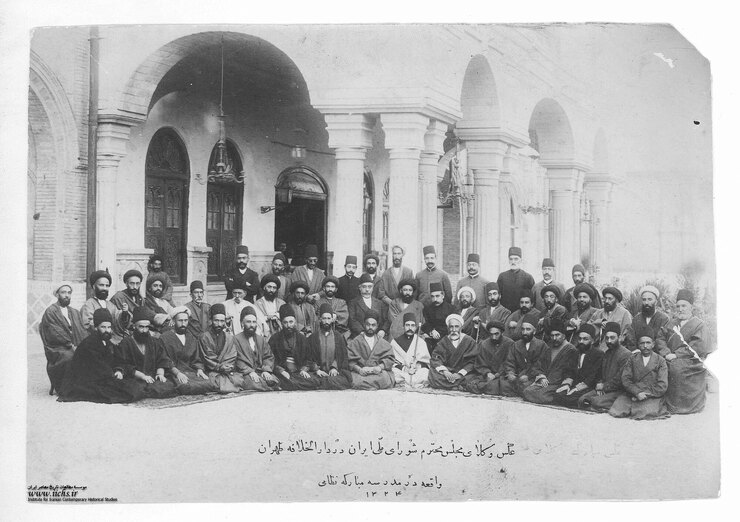

In the fall of 1906, after months of strikes and protests, Iranians were able to convince the Shah to order the establishment of the country’s very first parliament. On October 7th, the newly chosen members of Majlis gathered in Tehran to hold their first session. Marking a significant moment in Persia’s modern political history

The establishment of Majlis was seen as a major step towards the creation of a more democratic government. Yet, the path to democracy was long and yet to be navigated.

The first order of the new parliament was the creation of a new constitution for the country. The members wanted to base this new constitution on European countries like Belgium and France. At the same time, they also had to be careful not to overstep their power and anger the monarchy.

This fine line was navigated by the deliberate ambiguity of large sections of the constitution draft.

Members of the parliament wanted to keep the text vague and open for interpretation. This way, they could sneak their democratic agenda under the controlling gaze of the monarchy.

The new constitution didn’t mention anything about the rights of the people and limiting Shah’s unlimited power. However, it was made clear that no law could be validated without its approval and certification from the parliament. Majlis was now the only credible legislative branch of the government.

The new draft also established that each edition of the parliament would last for two years and members-elect of the chamber would be in charge of the country’s laws, budget, loans and any concession granted to the foreign nations.

While members were busy drafting the document, Mozaffar-al-din Shah, the monarch who had ordered the establishment of majles, was dealing with serious health issues.

Just like his father, Mozaffar’s lavish lifestyle had contributed significantly to Iran’s economic decline. It also had taken its toll on his health. Now at the age of 50, he was gravely sick and doctors weren’t hopeful of his recovery. As the shadow of death loomed closer to the king, the court was preparing itself for another transition of power.

The person chosen to take Mozaffar’s place was his son Mohammad Ali Mirza.

Initially, Mohammad was a strong ally of the protestors and supported their early claims from inside the court. But after the people’s call for parliament, he had become a fierce opponent of the constitutionalists. He was inspired by his late grandfather and wanted to bring back the absolute power of the monarchy to the house of Qajar.

With Mozaffar on his deathbed and Mohammad Ali gunning for the destruction of the parliament, the members rushed to finalize the draft of the constitution and get it signed by the shah before it was too late.

On December 30th, 1906, the parliament finally presented their proposed constitution to the king. He shortly approved of the text and signed it into action.

Five days later, Mozaffar-al-din Shah died and his son, Mohammad Ali came to power. Determined to cancel the newly found majles and to shut down Persia’s very shortlived democracy.

Hello,

My name is Oriana and you’re listening to The Lion and the Sun: A modern history of Iran.

Mohammad Ali Shah: From Humble Beginning to Full Tyrany

Mohammad Ali Mirza was the oldest son of Mozaffar. His mother was Taj-ol-Molook, the first wife of the shah and the daughter of Amir Kabir, One of Iran’s most consequential politicians of that era.

Amir Kabir was the grand-vizir under King Nasser al-Din Shah from 1848 to 1851. He was one of the most influential figures in the early constitutionalist movement in Iran. Amir Kabir initiated various reforms aimed at modernizing and westernizing the country. These reforms included improvements to the army, agriculture, and the education system. He also played a crucial role in the establishment of Iran’s first modern college, Dar al-Funun. One could say that he was the mastermind behind the cascade of events that ultimately led to the constitutional revolution.

Amir Kabir was eventually accused of undermining the power of the king and religious clergy. He was removed from his position, sentenced to prison and ultimately assassinated in 1852.

Despite being the grandson of one of Persia’s fiercest warriors of progression, Mohammad Ali was bent on regressing the country into the “glory” days of Nasir-Al-Din Shah.

Before his ascension to the crown, Mohammad Ali, afraid that the constitutionalists would back his uncle’s claim to the throne, played a supportive role to the movement. He was the one who convinced Mozaffar to accept the original demands of the people. He also acted as a mediator between the protestors and the crown.

But after becoming king, he changed course.

The Russian Influence

As mentioned in the previous episode, the British government championed the cause of the people. Their embassy became a sanctuary for protestors, offering them vital support in their resistance against the monarchy.

In contrast, the Russians seemed to be playing a different game.

From a young age, Mohammad Ali had shown affinity towards Russia. His perspectives were shaped significantly by Seraya Shapshal, his Russian tutor. This bond, combined with the geopolitical dynamics, meant that the new king felt a deeper connection to Persia’s northern neighbours. The Russians, recognizing this rapport, more closely aligned with his anti-constitutional views on Persian politics.

For his coronation, Mohammad Ali refused to invite members of the parliament. Moreover, in one of his first acts as king, he removed Moshir-al-dowleh. Moshir-al-dowleh was the grand-vizir of his father who had a helping hand in the establishment of the parliament. The new king refused to inform the parliament of his cabinet picks and took a stance against most of their reforms and proposed changes.

The biggest showdown between the court and the parliament, however, came the following year and through the changes made to the constitution.

Rewriting the Constitution

As mentioned before, during the winter of 1906, the members of the parliament rushed to finish their proposed constitution so that the sick shah could sign it before his death. This led to significant shortcomings in the final text. The new constitution had many vague and unexplained parts that made the job of legislative and executive branches impossible. That’s why the members decided to draft a new amendment to the constitution. This way they could add more previsions and clarity to the original text.

During this time, the unity between the constitutionalists was also on the brink of collapse and finding common ground for certain issues was becoming harder by the day. The amendment highlighted principles of freedom and equality for all Iranians. This did not sit well with the religious faction of the constitutionalists. They perceived these principles as incompatible with Sharia law and Islam’s supremacy. They believed that people and their democracy should never undermine the laws put in place by god and religion.

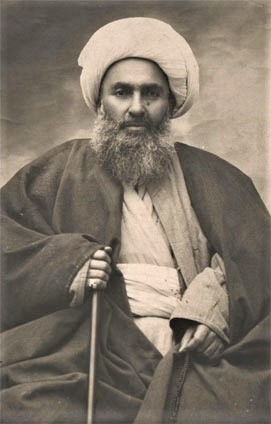

One of these clergymen, Fazlullah Nouri, who was a strong supporter of the people, became a harsh critic of the parliament. He insisted that a separate assembly, consisting of wise Shia clergies should be put in charge. To make sure none of the laws passed in the majlis were against the word of God.

Mohammad Ali Shah, noticing the rift between the religious and secular constitutionalists, decided to exploit it to sow further discord among the members.

Borrowing from Belgium’s constitution, the new provisions empowered the parliament to impeach any of the Shah’s cabinet members and directly oversee military expenditure. This turned Shah into a fierce opponent of the amendment. He employed every tactic at his disposal to thwart the amendment’s passage.

Mohammad Ali Shah contended that his resistance stemmed from the parliament’s departure from divine guidance. He asserted that his interpretation of the “constitution” was rooted in Islamic principles rather than “European” ideals.

Mohammad Ali’s strategy bore fruit. The once-dynamic parliament, which had swiftly enacted groundbreaking legislation, now spent most of its time in-fighting amongst its members. The legislative branch was effectively crippled.

However, another unfolding incident compelled its members to momentarily set aside their differences and unite once again.

Anglo-Russian Convention

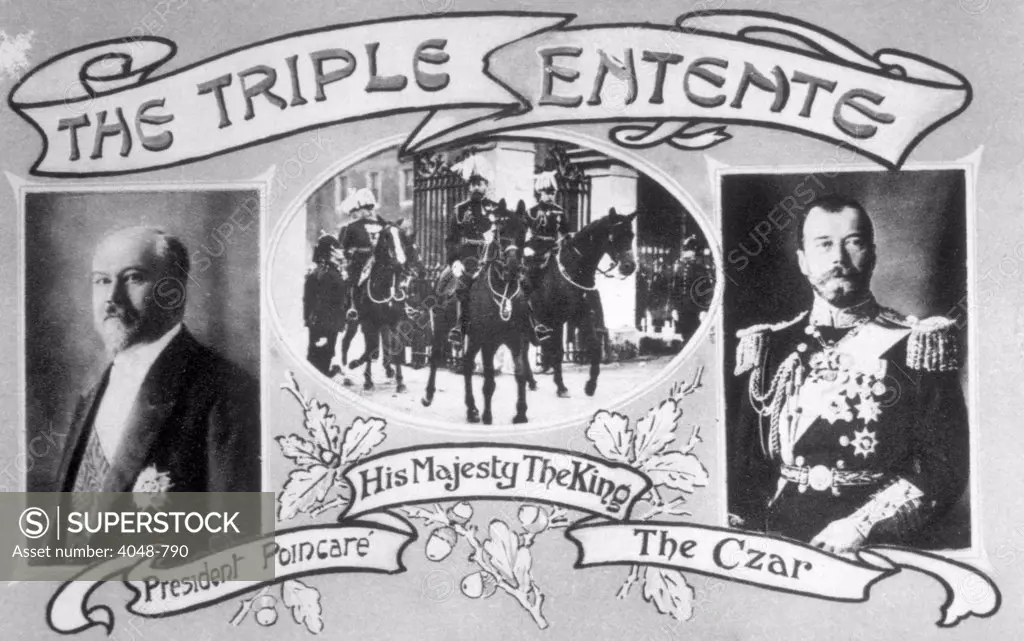

The Triple Entente was a pivotal military alliance established in 1907, consisting of the United Kingdom, France, and Russia. It was formed in reaction to the expanding influence of the German Empire and to counterbalance the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. Under this understanding, the three nations committed to mutual support should any face aggression from other European powers.

As a result of this alliance, on August 31st, 1907, the Anglo-Russian Convention was signed between the two superpowers.

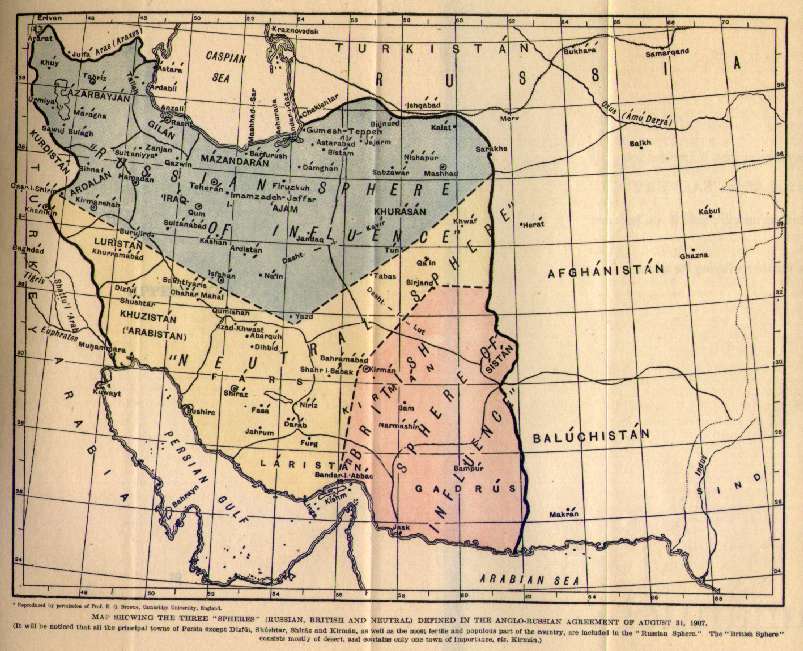

The convention aimed to stabilize the power dynamics in the contested regions of Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet. Under the agreement, Persia was delineated into two distinct spheres of influence. Russia dominated the northern regions, while Britain held sway in the southern territories. The central portion was designated as a neutral zone, reserved for the Persians themselves.

Despite the parliament’s emphasis on Iran’s sovereignty, none of the members were even consulted for this agreement and the convention was signed without their knowledge. In response to this act, many of the constitutionalists came out to the streets of Tehran and protested against the influence of foreign powers over Persia.

Russia, fearing the protests would grow out of control, put their full support behind Mohammad Ali Shah and gave him a massive sum to take back control of the capital.

Crisis of Sovereignty

The job of calming the constitutionalists was put on Amin-Al-Soltan, Shah’s grand-vizir.

Amin-Al-Soltan had previously served as the governor of multiple provinces in Iran. He was also appointed as a minister in the government. He was the grand-vizir in the Nasir-Al-Din Shah era and with Mohammad Ali Shah’s longing for the “good old days”, upon taking power, he immediately brought him back as his grand-vizir.

Now Amin-Al-Soltan had the difficult job of calming a very turbulent and angry Majlis and the great Persian populace.

He did so by finding a middle ground between the monarchy and the parliament. He tried to convince the members to support the Russian presence. In turn, negotiated with Shah to approve the new amendment to the constitution.

On October 1st, 1906, he visited the parliament to announce that the Shah had sanctioned the amendment to be signed into law, hoping to curry favour with its members. After addressing the assembly, he engaged in conversations with a handful of representatives before departing the parliamentary premises shortly after midnight.

Upon his exit, Amin al Soltan was fatally shot three times and succumbed to his injuries on the spot. The assailant was apprehended a few blocks from the parliament. But he took his own life before he could be detained further.

Nobody knew who or which group was responsible for Amin-Al-Soltan’s assassination. Some thought Shah himself was behind the attack. Some perceived that the British officials, angry with Soltan’s support for the Russians, gave the order. Others saw the killer’s connection to one of the constitutionalist groups as proof that the parliament itself had masterminded the whole thing.

A (Temporarily) Changed Shah

Shah, spooked by the assassination, signed the amendment into law and the tensions ceased for a while. Mohammad Ali Shah seemed like a changed man. He would periodically pen letters to the parliament expressing his commitment and allegiance to the democratic cause. Yet, behind the scenes, he continued clandestine meetings with anti-constitutionalists, seeking avenues to cripple the legislative body.

During this period, with the apparent reprieve from monarchical interference, the parliament regained its footing and embarked on implementing transformative reforms across the country.

The progressive faction undertook a reorganization of the chamber’s seats to ensure better representation from the nation’s remote regions. They advocated for the removal of religious prerequisites, championing the idea that individuals of any belief should be eligible for membership. Additionally, they took decisive measures to curtail the monarchy’s expenditures, effectively reining in Mohammad Ali Shah’s self-indulging spending habits.

Mohammad Ali Shah, enraged by these actions; still had to show the outward pretense of support for the parliament. But in truth, he sought out ways to combat them. His plan was to weaponize gangs of Tehran and send them towards Majles headquarters, demanding that the members stop with their slaughter of Persian traditions.

Islam vs. Democracy

Fazlullah Nouri, the religious constitutionalist, saw the progressive changes as the last straw and a clear threat to Islam.

In December 1907, supporters of these two figures orchestrated several assaults on the parliament. They gathered in prominent areas like Bahar-Stan and Toop-Kane squares, vocalizing their dissent with anti-constitutional slogans. Fazlullah Nouri delivered impassioned speeches, condemning the so-called sins of the “constitutionalist-infidels” to religious factions. As days progressed, these gangs became increasingly intoxicated and their aggression escalated.

As the anti-parliament coalition was growing bigger by the day, the people, fearing that the Persian democracy might end soon, came together to form another alliance against their barrage.

Different factions of the parliament, multiple unions and people of the bazaar stopped working in protests and gathered in mass to protect the majlis building. They repurposed a mosque and used it as their defensive headquarters. Each union and fracture took one of the rooms. Together, they began hosting inspirational talks and speeches in the middle of the mosque. Ultimately, the two opposing sides met in front of the parliament for a showdown. The gangs wanted to attack and capture the parliament building but the sheer amount of people who came out in its defence was too large to ignore.

After a few days of hostility, the mobs had no choice but to disperse.

After these events, Mohammad Ali Shah once again vowed to protect constitutional democracy. He wrote an oath on the back of the Quran solidifying his commitment to safeguarding the parliament.

Democracy was protected once more and this time, it seemed that the peace was there to last.

After the incident, the negotiations between Mohammad Ali Shah and the parliament showed great results. Both parties were willing to find common ground and a way out of the crisis.

Little did they know, peace would soon be explosively interrupted.

Assassination of Mohammad Ali Shah

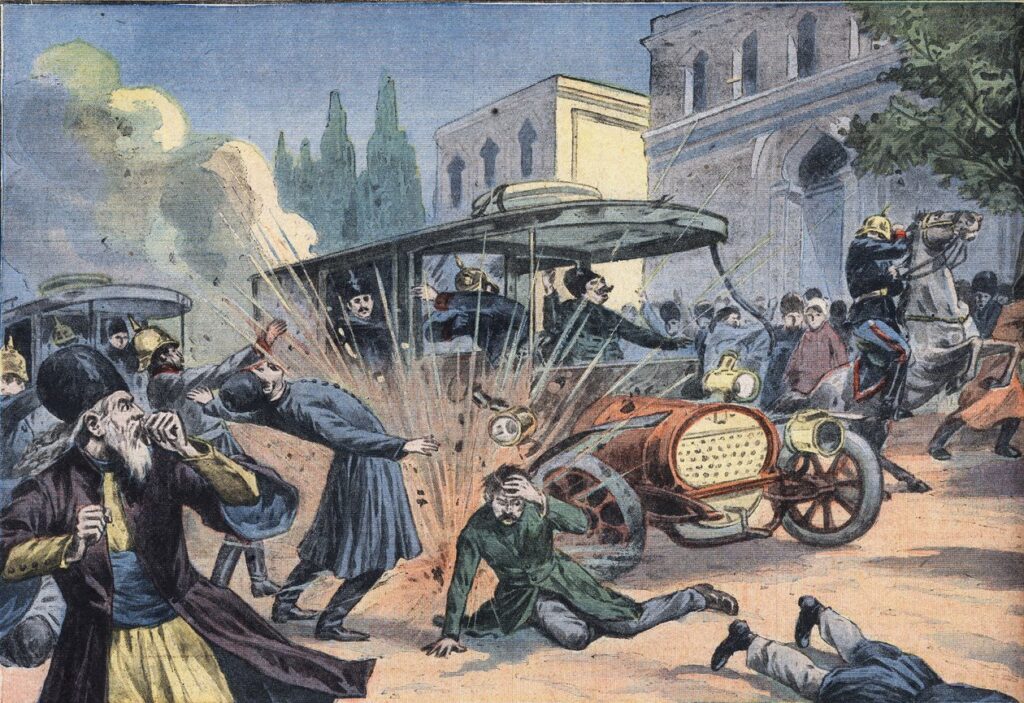

On February 29th, 1908, while the Shah, accompanied by another vehicle filled with close confidants, was taking a carriage tour through the streets of Tehran, a homemade bomb was hurled in his direction.

Following a deafening blast, both vehicles halted in confusion. As a visibly shaken Shah emerged to assess the situation, a second bomb detonated from a nearby store, claiming the lives of several members of the royal entourage. Gunfire then rang out from another store. Amidst the chaos, Shah’s team hastily ushered him into a neighbouring house for refuge, awaiting police intervention.

Despite several casualties, The attempt on Shah’s life was ultimately a failure. It was implied that the Amion, a democratic socialist party was behind the attack. Shah himself, however, thought otherwise. He feared that his uncle was behind the attempt.

Mohammad Ali Shah’s uncle, being older than Mozaffar, was once closer in line to the throne. However, his claim was undermined because his mother was not of pure Qajar lineage. Now, Mohammad Ali felt a rising anxiety, suspecting that his uncle had ambitions to reclaim the throne from him.

Post-Assassination: Shadow of Paranoia

In the aftermath of the assassination, Shah apprehended a few of the suspects. He confined them in Golestan Palace, a historically significant building of the Qajar dynasty and held them captive. They were subjected to rigorous interrogation in the hopes that one of them would confess the truth and those behind it.

The parliament took issue with the actions of the Shah. They maintained that this type of behaviour was exactly the kind of power abuse they were planning to fight. They demanded that Shah give up the prisoners to the justice ministry for proper prosecution.

Shah saw his actions as rational and reasonable. His life was put at risk so he was going to make sure the responsible parties paid for their sins. The dispute over prisoners once again reminded Mohammad Ali Shah how the monarchy had become powerless with the existence of the parliament. He knew then that as long as this legislative body existed, the golden era of the Qajars could not be restored.

In April of 1908, various sources within the court and the parliament began issuing warnings about the latest plans of Mohammad Ali Shah. Ever since the assassination attempt, fearing for his life, Mohammad Ali Shah had refused to leave the Golestaan palace. His only companions during this self-imposed isolation were his former Russian tutor and a select group of confidants. All of whom held strong affiliations with the Russian Empire and voiced opposition to the parliament’s authority.

As Shah grew more isolated and paranoid, the infighting among the members of the parliament increased. The once united chamber now consisted of numerous factions, each seeking their own political agenda and each refusing to cooperate with the rest. Some believed that the only path forward was appeasement toward the Shah to prevent further escalation. Others had completely given up on the idea of a constitution and just wanted to protect their lives and interests. A few wanted a more strict oversight on the monarchy, to exhibit the power of the chamber. And the religious members just wanted to safeguard their ideology and traditions.

All this infighting turned the once progressive and pragmatist majlis into a gridlocked idle body.

A shadow of its former glory.

In the summer of 1908, after a series of minor uprisings in Tehran, Mohammad Ali Shah decided to migrate from the Golestan Palace and take shelter in Bagh Shah.

Bagh Shah or the king’s garden, was a place of leisure and entertainment for the royal family and members of the court. It was also a location for various events and ceremonies, including state receptions and official banquets. Bagh Shah was renowned for its beauty but it was also a strategic stronghold. Located outside of the city center, the garden wasn’t as exposed as the Golestan Palace and had a strong structure that allowed for military protection.

Attack on the Parliament

After Shah settled within the building, the cossack brigade, the Russian-supported and trained fraction of the army, was put in charge of its defence. In a letter to Tehran, Shah explained that he had relocated due to Tehran’s heat and would manage the day-to-day affairs of the country from his new base. Within days, he undertook a comprehensive reshuffling of his central administration.

New appointments were made to critical positions, including the heads of Tehran’s police and the city’s governorship. These orders were not consulted with Majles and the members started criticizing Shah for his authoritarian rule.

Shah, ignoring the criticisms, wrote a letter to the parliament and demanded reforms to the press, setting limitations to what unions and institutions could do, and finally firing some radical constitutionalists from the chamber. The letter titled “The roadmap to survival and hope for the nation” made it clear that despite the constitutional nature of the country, corruption and wrongdoing would still be punished; and stepping out of line would be met with grave repercussions.

Members of the parliament took Mohammad Ali Shah’s letter as a clear threat to democracy. On June 9th, the people came back to the streets near the parliament to protect its safety.

Echoing the events of the previous December, supporters of the constitutional movement took refuge in a nearby mosque. They signalled unequivocally that any threat to the parliament’s security would be met with resistance. They organized rotating shifts to guard the building, ensuring a constant presence of at least 100 people on-site at all times to deter any potential aggressions.

But this time, Shah wasn’t going to back down.

On June 22nd, he ordered what was effectively martial law. Forbidding large gatherings in public places, made carrying firearms illegal, and gave police the right to shoot anyone who disobeyed their direct orders.

With these restrictions in place, the masses dispersed, the streets emptied and the parliament building was left undefended.

Now Mohammad Ali Shah could finally achieve what he had dreamed of since his first day as Persia’s ruler. Now he could finally put an end to the “Persian Awakening”

One Response