This is the transcript for Book One, episode 6 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: Russian Roulette about Iran Russia relationship in the Qajar dynasty. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

Mohammad Ali Shah’s Reign: A Period of Change and Resistance

The almost three-year rule of Mohammad Ali Shah coincided with a period of profound change. The push for constitutionalism and the opening of parliament were just a few signs of the Iranian people’s thirst for progress. However, the person leading the country during this era was the antithesis of their aspirations.

As a conservative king who yearned for a return to the golden age of his grandfather, Mohammad Ali Shah did everything in his power to hinder the progress made by the Iranian people.

The Constitutionalists’ Victory and Mohammad Ali Shah’s Exile

But on July 13th, 1909, as the constitutionalists’ forces were close to conquering the capital, he had no choice but to give up his pursuit of conservatism and escape to the only place where he would be safe.

After Tehran was captured, the constitutionalists wanted a fresh start. They didn’t want to seem vindictive or looking for settling personal grudges. Therefore, the committee in charge of restoring peace to Tehran made the deal with the ex-shah to safely leave the country and allowed him to take shelter in Russia.

The directorate in charge of negotiating Mohammad Ali Shah’s exile even granted a hefty monthly salary of 1000 rials equal to 100 dollars for him. This was to prevent angering the hardcore monarchists of the previous era.

Following his abdication, the constitutionalists were eager to relegate Mohammad Ali Shah’s reign to the history books. They wanted to focus on rebuilding the country.

However, the exiled Shah had different intentions.

Mohammad Ali Shah’s Attempted Return: The 1911 Coup

In July 1911, news came to Tehran that the deposed Shah had returned to Iran with an army. He had entered the country through a northeastern port on the Caspian Sea. The exiled Shah had arrived on a Russian ship. He had a few thousand troops aiding him, consisting of Turkmen tribesmen from the region. As the constitutionalists scrambled to muster a force to confront the rebellion, they learned that the ex-king was not alone. His younger brother along with an army of Kurdish fighters, had joined him to restore his rule to the land.

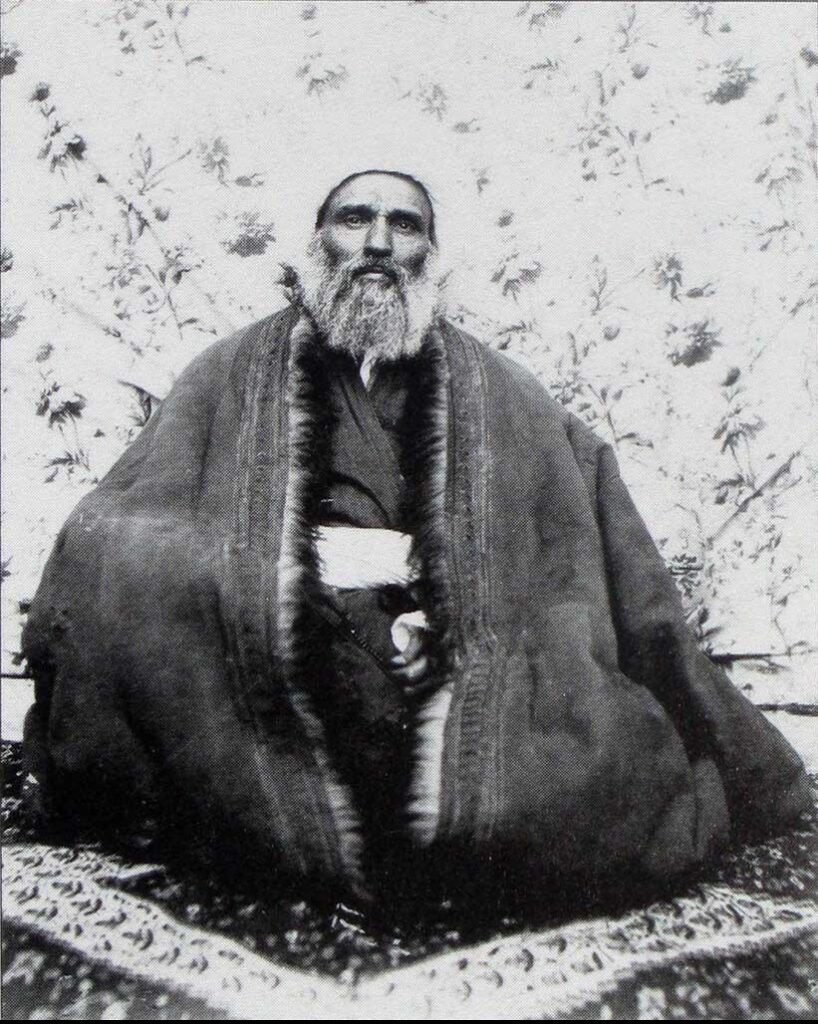

Salar-ed-Dowleh was Mozaffar’s third son and Mohammad Ali’s younger brother. After the deposition of his brother, he had met with him outside of the country where they planned their coup to take back the country and restore the original monarchy.

[salar al-dole photo]

Their objective was straightforward. Mohammad Ali would lead an offensive from the Caspian Sea in the north. Salar-ed-Dowleh would strike from the northwest. After capturing their ancestral city of Tabriz, the two armies would join forces. Finally, they would march to Tehran to regain power.

While the skirmish was underway, the government had grave concerns about their chances. Tehran was still filled with people from the previous era and loyal to the deposed king. The old-guard Qajar loyalists were still integrated into the court and they might not have been able to prevent Mohammad Ali’s return to the throne.

As the coup continued, constitutionalists once again called on Bakhtiary riders to come to their help. The government also put a warrant for Mohammad Ali Shah, dead or alive. They set a prize of 237,000 dollars for his capture.

With Bakhtiary riders getting closer to Tabriz and dead set on bringing the shah’s corpse to the capital, Mohammad Ali spooked and scared for his life, got on his ship he came and fled back to Russia, never to see his country again.

Russia and Persia: A Historical Overview

The relationship between Russia and Persia dates back centuries and has been marked by periods of both cooperation and conflict.

The earliest recorded contact between the two cultures was in the 16th century when Tsar Ivan IV (also known as Ivan the Terrible) sent an embassy to Persia. At the time, both Russia and Persia were expanding their empires and saw opportunities for trade and diplomacy.

During the Safavid empire and until the mid-18th century, Russia and Persia’s relationship was peaceful and to some extent cooperative. Both powers sought to counter the growing threat of the Ottoman Empire.

However, tensions arose as Russia expanded southward into the Caspian Sea region, encroaching on Persian territory and disrupting trade routes. These tensions led to several Russo-Persian wars in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Russo-Persian Wars: Territorial Disputes and Power Struggles

The Russo-Persian Wars (1651 – 1828) were a series of conflicts rooted in territorial disputes between the Russian Empire and Persia. Particularly over regions in the Caucasus such as Aran, Georgia, Armenia, and much of Dagestan, collectively referred to as Transcaucasia.

In the early days of the Qajar dynasty, Fath Ali Shah, aimed to reclaim the northernmost areas of his realm—particularly modern-day Georgia—that had been annexed by Tsar Paul I of Russia following the Russo-Persian War of 1796.

The military engagements during these wars underscored the asymmetry in military capabilities between the adversaries. Despite often being numerically outnumbered by the Persians, Russian forces were able to leverage superior tactics, weapons, and sometimes external geopolitical circumstances to their advantage to defeat the Qajar forces time and time again.

The outcomes of these wars significantly altered the regional geopolitical landscape. Treaties concluding the wars, such as the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), resulted in Persia ceding substantial territories to Russia, including regions of modern-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Dagestan.

In the late 19th century, Persia was becoming increasingly reliant on foreign loans. The country struggled to modernize its military and infrastructure.

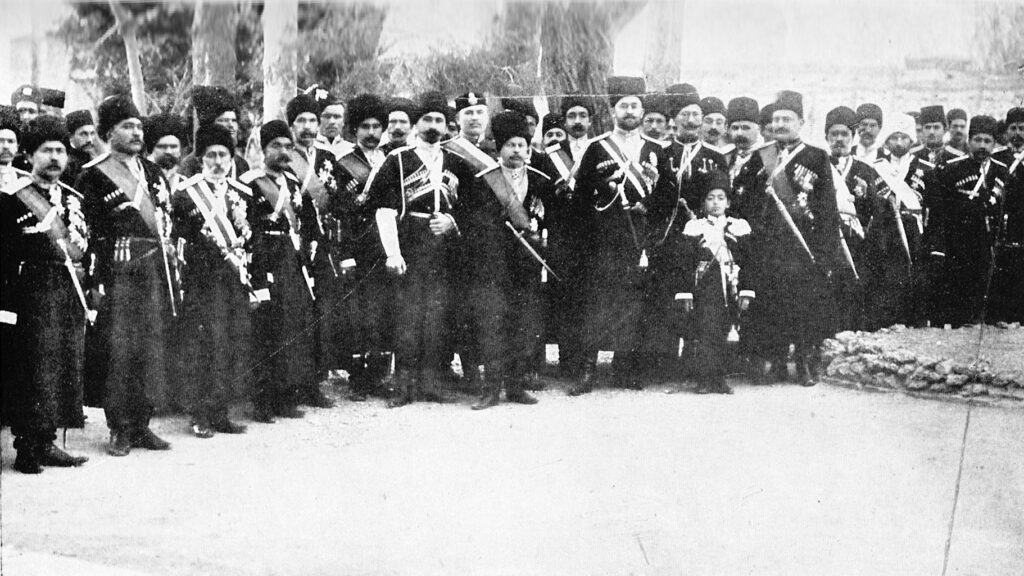

The Persian Cossack Brigade: Russian Influence in Iranian Military

In 1878, during his second journey to Europe, Nasir al-Din Shah of Iran was greatly impressed by the Russian Cossacks’. The army’s discipline and military prowess impressed him across Transcaucasia. This experience inspired the formation of the Persian Cossack Brigade in 1879, modelled after Russian Cossack formations.

The Shah, with the aid of Russian military advisors, established this unit. This branch aimed to foster a disciplined, reliable fighting force within Iran. What started as a regiment under the command of Russian officers, quickly expanded into a brigade due to the Shah’s keen interest and the evident progress in its training and organization.

The Persian Cossack Brigade marked a significant step towards military modernization in Iran. Its formation reflected the Shah’s desire for a modernized force. It also showed the growing Russian influence in Iran during this period.

Russia and other European powers saw Persia as a potential sphere of influence. They competed for economic and political control in the region. In 1907, Russia and Britain reached an agreement to divide Persia into two spheres of influence. With Russia controlling the north and Britain controlling the south.

During the reign of Mohammad Ali Shah, Russia gained immense powers and influence over the Persian kingdom. The Russian cossack brigade was acting as Shah’s private army and most of his close advisors had ties to the northern empire.

When Mohammad Ali attempted to retake the empire, it was clear that he had support from St. Petersburg. Russia has always been against the constitution and rule of the people. This was their attempt to once again tighten their grip on their southern neighbours.

As Mohammad Ali Mirza marched his army towards Tehran, the lack of any condemnation or objection from the Russian authorities was conspicuous. Despite the constitutionalists’ efforts to appease the Russian empire and the presence of their cossack brigade, the Russians still perceived the new order as a danger to their interests. They were hoping that by staying clear of Mohammad Ali Mirza’s coup attempt, they’d once again find their footing in Persian.

Regrettably, this deliberate silence only served to further tarnish the already strained relations between the two neighbours. This non-response from Russia only served to set the stage for an inevitable and potentially dangerous future confrontation.

After the nationalists marched to Tehran, a mandate was set to sort out the finances of the country. With the overspending habits of the previous king, Persia’s debt to other countries and the corruption rampant at every office, Iran had a huge revenue problem. To make sure that the country’s finances were well managed, the court reached out to the US State Department to receive a recommendation for a financial advisor.

To the eyes of the Persian government, the United States seemed a safe choice for getting recommendations from. Unlike the European powers and Persia’s northern neighbour, the United States had little limited presence in the country.

The first official contact between the United States and Persia occurred in 1856. When the Persian government appointed a consul in Washington, D.C. In 1883, the U.S. reciprocated by sending Samuel Benjamin as a consul to Persia.

Throughout the 19th century, American missionaries established schools and medical facilities in Iran. This helped to create a positive image of the United States among the Iranian people. This period also saw increased trade between the two countries, albeit limited in scope. Mainly because the US wanted to stay away from the Anglo-Russian zones of influence.

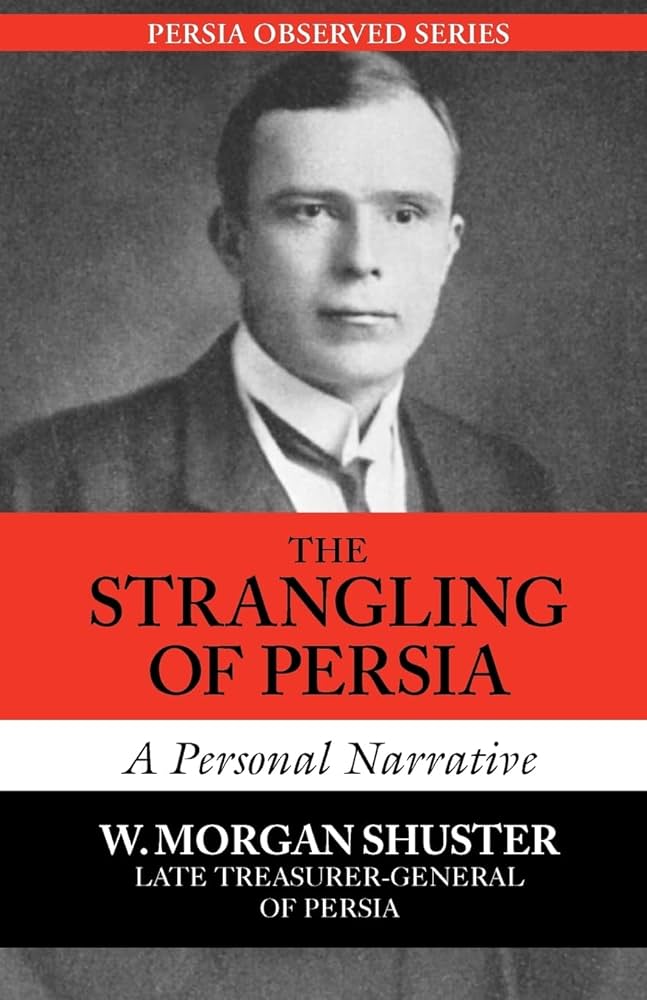

William Morgan Shuster: America’s Financial Advisor to Iran

In 1911, at the behest of the Iranian legation in Washington, the US State Department recommended William Morgan Shuster to serve as a treasurer general for the government of Persia.

William Morgan Shuster was an American lawyer, civil servant, and financial expert. He was well-known in the US government for his integrity and candour. Shuster was invited by the Iranian government to help reorganize and modernize the country’s financial system.

Shuster’s tenure as Treasurer-General was marked by his efforts to bring transparency and accountability to Iran’s finances. He established a new system of tax collection. Worked to reduce corruption, and fought against foreign intervention in Iran’s financial affairs.

However, his reforms and strong stance against foreign influence angered both Britain and Russia.

After Mohammad Ali Mirza’s failed coup attempt, the parliament authorized Shuster to confiscate their properties. This included Salar-ed-Dowleh, Mohammad Ali’s brother who was a co-conspirator in the coup ploy.

Shuster planned on seizing the prince’s residence, but the Russians intervened. They instructed the cossack officers to occupy the palace and deny entry to Shuster’s team. The Russian government’s argument was based on the fact that the prince had secured a loan from the Russian Mortgage Bank, and as a result, the palace served as collateral that belonged to Russia. Additionally, they asserted that Salar-ed-Dowleh was a Russian protege. This meant that he was under their protection, therefore the government had no right to seize his property.

Despite Russia’s apparent involvement in the recent coup attempt and its meddling in the internal affairs of the country, the Persian government still yielded to their pressure. In an attempt to diffuse the tensions, the Minister of Foreign Affairs ordered Shuster to stand down and extended a personal apology to the Russian team on behalf of the government.

The Russian Ultimatum: Challenging Iran’s Sovereignty

Seeing Iran’s fear of a showdown, Russia decided to push harder with what it wanted. They figured that Iran wasn’t in a good place to have a foe on its northern border. In November 1911, the Russian government gave another ultimatum to Persia.

They said that due to his transgressions, the government must dismiss Morgan Shuster from his post as treasurer-general. Russians demanded that Shuster’s entire team get sent back to the US. They also made an insertion that Persia was not to engage the help and service of other countries without the consent of the Russians and the British. Finally, they demanded that the Persian government should pay for the cost of Russian troops deployed in the region. Meaning that Iran had to pay and feed the foreign invaders settling inside its borders.

The sheer audacity of the Russians angered the Persian community. Nationwide protests of outrage took place in various Iranian cities with clergies making speeches in mosques in support of Shuster. This was the first instance that the religious community was putting its support and influence behind a foreign individual. It showed the level of respect the community held for Shuster and his reforms.

Religious Leaders Take on Russia

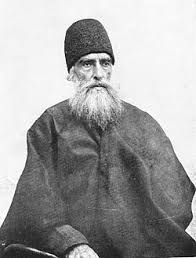

This nationwide outcry was led by Mohammad Kazem Khorasani. Khorasani was a prominent Shia jurist and philosopher active in the country’s politics since the late 19th century. Born in Tous, Iran, he studied in Najaf, Iraq, where he became an influential religious scholar and later a Marja, a top-ranking Shia religious authority.

During the reign of Mohammad Ali Shah, When Sheikh Fazlollah Noori issued the fatwah for the death of the protestors for their resistance towards monarchy, Khorasani retaliated by announcing that Sheikh Fazlollah was himself no longer a Muslim, leading to Fazlollah’s execution

Khorasani, a student of Mirza Shirazi, the influential cleric responsible for the tobacco fatwa, understood the vital role religious figures could play in political struggles. Following the Russian ultimatum, he assumed a leadership position in the battle against the meddling of Persia’s northern neighbours.

With a resolute mandate and the support of the public, the parliament defied the orders of the Russian regime by rejecting their ultimatum at the eleventh hour. Yet despite the people’s and parliament’s stance against the ultimatum, another obstacle brought their momentum to a halt.

After the initial wave of protests, Khorasani was getting ready to move back to Tehran and issue a religious order, similar to Shirazi’s fatwah against tobacco. He wanted to hold the Russians accountable and declare Jihad against their forces. But before embarking on his journey, on December 13th, 1911, Khoarasani died under mysterious circumstances.

While there was no concrete evidence pointing to the Russians, many speculated that it was the two superpowers that had planned the inconspicuous murder of the prominent clergy.

Ultimately and regardless of the intentions, Khoarasani’s death resulted in the demoralization of the public. It also gave Russians the perfect opportunity to strongarm Persia into submission.

Russian Occupation of Tabriz: A Brutal Campaign

After parliament’s stance against the empire, Russia ordered its forces to enter the country through the northwestern borders and recapture the city of Tabriz. Despite the fight put on by the remnants of the Sattar Khan’s army, the Russian forces were ultimately successful in taking the city.

Their army, comprised of more than 5000 soldiers, unleashed a brutal campaign of destruction and savagery, leaving in their wake a trail of rape, plunder, and death. The city was engulfed by an ominous cloud of fear and horror, casting a sombre spell over the community. The corpses of those executed by the merciless invaders dangled lifelessly from the gallows for days as a chilling reminder of the city’s tragic fate. The streets, once bustling with life, were now silent and empty, the echoes of terror reverberating through the emptiness.

Gradually, city by city, the Russian army managed to occupy their entire agreed-upon sphere of influence in northern Persia. To keep up with the ambitions of their regional partners, the British also expanded their presence in the south. They managed to move up parts of the Indian army through the Persian Gulf and stationed them within Persia.

As the unofficial occupation of Persia by the two superpowers went on, the crisis in Tehran reached unprecedented heights.

The parliament was still adamant in standing against Russia’s ultimatum, but the executive branch found itself facing a difficult situation with the growing Russian military presence in the north and Britians in the south. Ultimately, the government felt cornered and yielded to the mounting pressure exerted by Russia.

In a consequential move, the government declared its intention to remove Shuster from his official role. In reaction, the Majlis—Persia’s parliament—unanimously passed a vote of no confidence against the grand vizir, Najaf-Qoli Khan Bakhtiary.

Bakhtiary was a pro-British leader who had assumed power after the short-lived rule of Sepahdar, the military commander pivotal in the liberation of Tehran.

Najaf-Qoli Khan was a proponent of adhering to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, an agreement that had effectively partitioned Persia into northern and southern zones, each under the sway of a different foreign power. His stance met with severe disapproval from the Majlis, prompting him to tender his resignation.

Nevertheless, even the departure of the Shah’s Grand Vizir wasn’t sufficient to quell the relentless Russian pressure.

As mentioned in the previous episode, due to Ahmad Shah’s young age at the time of ascension to the throne, a council of constitutional activists appointed Azad-ol-molk as his acting regent.

Azad-ol-molk, a patriarch of the Qajar dynasty, was commonly referred to as the “honourable uncle.” Upon his death on September 23, 1910, the parliament selected Naser-al-Molk as the second regent for the youthful king.

Educated at Oxford and hailing from a wealthy, influential family, Naser-al-Molk possessed a nuanced understanding of Persia’s geopolitical landscape. However, despite his qualifications, he was inherently cautious and refrained from taking assertive actions that could potentially provoke foreign powers.

Confronted with the reality of thousands of Russian troops residing in the country’s northern regions, the risk of a full-scale invasion weighed heavily on Naser-al-Molk. Feeling cornered, he opted to align with Najaf-Qoli Khan’s earlier decision to consent to Russian demands.

Consequently, he granted the newly-appointed prime minister the authority to undertake all necessary measures to safeguard the capital and avert a full-blown conflict with Russia.

The Fall of Iranian Parliament: Foreign Pressure and Internal Conflict

On December 24th, the grand vizir ordered his forces to march on the Majlis and occupy the building. The armed forces forcibly expelled all the representatives and threatened them with death if they attempted to convene parliamentary sessions elsewhere. After the occupation, the regent declared the parliament closed once again and suspended the constitutional procedures due to extraordinary circumstances.

The halls of the legislative body, the site of years of bitter infighting and political turmoil, now stood empty. A silent witness to the shifting tides of history. With the sudden dissolution of the parliament, the country once again fell under the shadow of full monarchy. A return to a time of unchecked power and the whims of the few. The people of Persia, who had long struggled for their voice to be heard, now found themselves adrift in a sea of uncertainty. They wondered what the future held in store for their beloved land.

Morgan Shuster’s Departure: The End of Hope

Finally, in January 1912, less than a year after their arrival, Morgan Shuster and his American team were forced to resign and leave the country they had once hoped to improve.

On the eve of their departure, a restless energy filled the air. The people poured into Baharestan Square in front of the now-sealed-off parliament. They wanted to voice their frustration and anger. The cries of “Independence or Death” echoed through the city blocks. A rallying chant for a people tired of the unending interference of foreign powers in their affairs.

Upon his return to the United States, Morgan Shuster published a personal recollection of his time in Persia. In his book, he provided a vivid portrayal of the aggression of European powers in the politics of the region.

In his book, he expressed deep disappointment at being “forcibly deprived of the opportunity to finish this intensely interesting task in that ancient land due to the recklessness of two powerful countries that played fast and loose with the laws and lives of the Iranian people”. Leading to what he saw as the hopelessness of Persia’s self-reorganization. Schuster dedicated his book to the Persian People. He described the destruction of the democratic experience as “a sordid ending to a gallant struggle for liberty and enlightenment.”

Following the departure of Shuster and the failure of the second Majlis, Persia found itself right back where it had started. A nation under the shadow of its powerful northern and southern neighbours. With a populace whose voices were silenced, and a monarchy that disregarded all the progress made over the previous decade. The promising strides toward democracy and self-determination had been cut short, reverting the country to the previous century.

But as Persia was at its lowest point, the world powers were gearing up for a gruesome war that would consume the next four years and lead to societal change in every nation and change the sphere of power within the region.

In the next episode of The Lion and the Sun, we would see the impact of World War 1 on Iran and the beginnings of the collapse of a once mighty Qajar empire.

2 Responses