The Oppressed Half: Women’s Status in Qajar Society

During the Qajar reign, women in Iran faced a highly restrictive social and economic environment. Their access to education was minimal. They had no right to ownership and they were seen as inferior to men. Gender segregation defined both private and public life. Strict boundaries dictated where women could go and how they interacted with men. Yet, Despite their limited public roles, women contributed significantly to the household economy, particularly in agriculture and domestic service. In this blog post, we’ll be taking a look into the status of women, during the Qajar dynasty.

The Patriarchy: Birth of Qajar Empire

The Qajar dynasty, which ruled Iran from 1794 to 1925, rose to power following a period of political chaos after the fall of the Zand dynasty. Agha Mohammad Khan, the founder of the Qajar dynasty, emerged victorious after a series of battles. He consolidated power by defeating rivals and reestablishing Iran’s sovereignty over territories such as Georgia and the Caucasus. His reign marked the beginning of Qajar control, though it was short-lived due to his assassination in 1797.

During the Qajar era, Iran experienced significant internal strife and external pressures, especially from Russia and Britain. Despite these challenges, the Qajar rulers maintained a rigid patriarchal structure that dominated social, legal, and political life. In season one of The Lion and the Sun podcast, we tell the story of the Qajar kings and how their actions led to the downfall of their empire. You can listen to us here.

Behind the Veil: Legal and Social Constraints

In the 18th century, Iran experienced a patriarchal and restricted social and legal status. This was governed largely by Islamic law (Shari’a) and deeply entrenched cultural traditions. Women’s roles were defined by their relationship to male family members—primarily as daughters, wives, and mothers. Their status was closely tied to their reproductive function, with their value often judged by the number of children they bore.

During this time, The legal system was deeply patriarchal. Women had limited property rights, with only about 1% of women owning property, as revealed in an 1852–1853 study from Tehran. Women were excluded from political and educational opportunities, with literacy being rare and stigmatized. (According to some estimates, only 3% of women were literate in the Qajar era) For example, many educated women, including wives of Naser al-Din Shah, hid their literacy from the public due to social pressure.

The legal framework favoured men heavily in marriage and divorce. Child marriages were common, and men could easily divorce their wives, often for trivial reasons like infertility. Divorce, although legal, was rare due to the stigma and harsh conditions women faced post-divorce.

The Double-Standard: Women’s Economic Contributions

Women contributed to the economy through various labour-intensive tasks such as animal husbandry and agriculture. Women also found employment in elite households as nurses and nannies, supporting affluent families by handling childcare and household duties.

Although women had limited participation in the market economy, some engaged in selling goods as street vendors or small-scale traders. Socially, women’s active participation in religious ceremonies, such as the mourning rituals during Muharram, provided them a visible but restricted public role

The Heart of the Home: Women’s Family Roles

In the Qajar era, women’s primary role within the family was centred on maintaining the household and nurturing children. As the central figure in the household, women were responsible for a variety of domestic duties. From cooking and cleaning to managing servants and caring for children.

Social norms reinforced the idea of female inferiority and strict gender segregation, particularly in urban areas. The andarun (inner quarters) symbolized both the physical and social confinement of women.

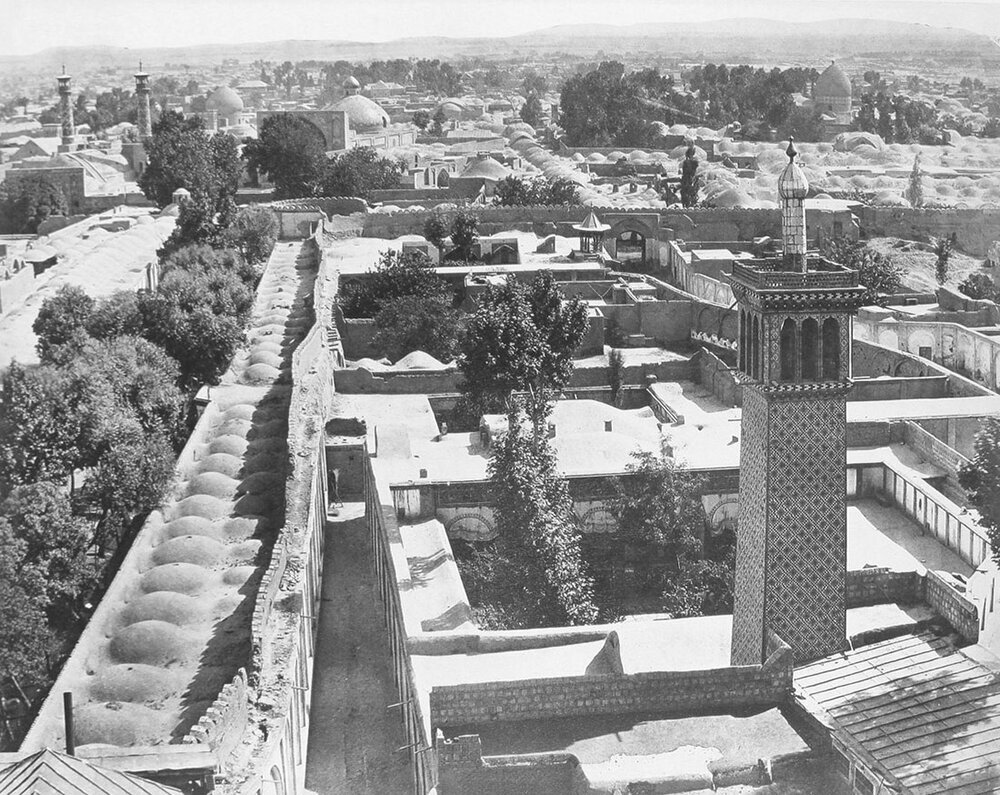

Andarun: Limiting Exposure Through Architecture

In traditional Iranian houses, the concept of Andarun and Birun reflected a clear separation between private family life and public social activities. The Andarun, or inner section, served as a secluded, intimate space where the family, particularly women, lived their daily lives away from the view of outsiders. It was often enclosed by high walls and featured gardens or courtyards, creating a peaceful environment focused on privacy. In contrast, the Birun, or outer section, was the public-facing part of the home. A place where men entertained guests, conducted business and held formal gatherings. This section was designed to be more open and impressive. It showcased the family’s status, while maintaining the sanctity of the Andarun.

Forced Dependency on the Male

Women were expected to adhere to modesty standards and remain dependent on male relatives. Women’s education was limited, and their public roles were minimal. Temporary marriage (siqeh), a practice sanctioned by Shi’a law, offered some women limited social mobility, especially in lower classes, but this too often led to exploitation.

Marriage was the cornerstone of a woman’s role in society. They were often arranged to benefit the family’s social, economic, or political status. Once married, women typically moved into their husband’s family home, where they were under the authority of their mother-in-law. A woman’s fertility played a crucial role in her standing. Those who could not produce male heirs often faced the possibility of their husbands marrying additional wives. Childless women or those who only bore daughters were generally considered less valuable.

Motherhood: The Contributions of Iranian Women in the Qajar Era

Mothers were especially respected, as they were seen as the emotional and moral anchor of the family. Their status within the family often depended on their ability to bear sons. Male heirs were viewed as the future and contributors to the family’s legacy. The survival and upbringing of male children were particularly important in securing a woman’s position within the household.

Women also played a significant role in protecting family honour. Their behaviour was seen as a direct reflection of the family’s reputation. Modesty was strictly enforced, with women expected to wear the chador and adhere to social norms that limited their interaction with men outside their immediate family. However, within the andaruni, women could exercise a degree of authority and influence, particularly in the management of household affairs.

Despite these restrictions, elite women in royal or noble families were sometimes able to exert significant influence behind the scenes, particularly in political matters. For instance, women like Mahd-e Olia, the mother of Naser al-Din Shah, wielded considerable power in shaping court decisions and succession issues. Though their public roles were limited, these women maintained networks of influence through patronage and strategic alliances with political and religious figures

Late Qajar Era and Women’s Education

During the Qajar era, education for women was minimal. Particularly in their early period, traditional societal norms limited women’s access to formal schooling. Most women received informal education at home, learning basic religious teachings and domestic skills. In this time, literacy rates for women were exceedingly low. By 1853, only about 3% of women were literate. There was a widespread belief that educating women was contrary to Islamic values, and literacy among women was often considered a social stigma. Many educated women concealed their literacy out of fear of public disapproval(Iran Chamber).

In the mid-19th century, missionary schools began to offer new educational opportunities for girls. Christian missionaries, particularly American Presbyterians and French Catholics, established schools primarily for religious minorities such as Armenians, Jews, and Assyrians. Over time, these schools opened their doors to Muslim girls, providing a Western-style education that included subjects like mathematics, geography, and science alongside religious studies. Schools like those established by the Alliance Israélite Universelle introduced secular subjects, contributing to a gradual cultural shift that recognized the importance of educating women.

The Seeds of Progress: Reformers and Revolutionaries

By the late Qajar period, Iranian reformers began establishing indigenous schools for girls. Key figures like Bibi Khanum Astarabadi and Sediqeh Dowlatabadi played pivotal roles in promoting women’s education. Astarabadi founded one of the first private schools for girls in Tehran and criticized the traditional treatment of women, arguing that education was essential for improving their status. Dowlatabadi, a feminist and social activist, was instrumental in opening several girls’ schools and published a women’s journal advocating for equal rights and education.

Despite these efforts, the expansion of women’s education faced significant resistance from conservative elements of society, particularly religious leaders who viewed it as a threat to traditional values. However, the momentum of the Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911) and the growing influence of reformist thinkers helped solidify women’s education as a critical aspect of social progress in Iran.

In the first season of The Lion and the Sun podcast, we see how a ban on tobacco jumpstarts the efforts for the constitutional revolution and how key figures such a Maryam Bakhtiary become influential in pushing the country into modernity. You can listen to our show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts from.

The Legacy of Qajar Women

The Qajar era was a time of stark gender inequality and rigid patriarchal control in Iran, where women’s roles were largely confined to the private sphere and dictated by social and religious norms. Despite these limitations, women played crucial roles in both the household and the economy, contributing to agricultural production and domestic work.

The gradual rise of educational opportunities and the advocacy of reformers in the late Qajar period marked the beginning of a shift toward recognizing the importance of women’s education and rights. While these advancements were met with resistance, they laid the groundwork for future progress. We’ll look at the role of women in the constitutional revolution in another blog post.