This is the transcript for Book One, episode 8 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: APOC about the discovery of oil in Iran and the creation of the Anglo Persian Oil Company. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

The Art of Concessions: D’Arcy’s Entry into Persia

For decades, the Qajar kings had honed their skills in the art of selling concessions to foreign governments and individuals. Despite the failures of the Reuters saga and the disastrous tobacco deal, they had become apt at navigating the political landscape with cunning and stealth, while also ensuring the satisfaction of those within their sphere of influence. As a result, Persia had become known as a country that was open for business. With every corner available for auction to potential buyers at a very reasonable price.

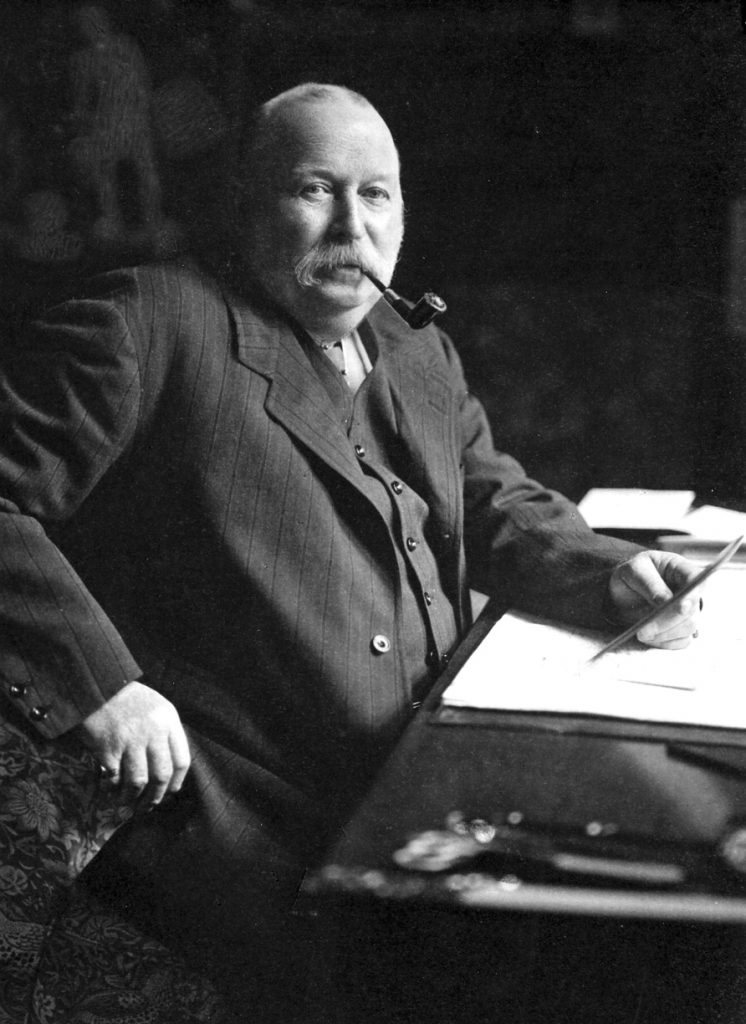

One of these buyers was William Knox D’arcy.

D’Arcy was born in Devon, England, in 1849. He started his career as a clerk in the City of London, where he gained experience in finance and business. He then went on to work in various other industries, including mining, banking, and shipping. After making a fortune in prospecting for gold in Australia, D’arcy was beginning to shift his attention to a different type of gold.

During the late 19th century, the internal combustion engine represented a crucial technological breakthrough. Something that was poised to revolutionize transportation and industry. However, the rapid adoption of this innovation necessitated an enormous supply of oil.

Whoever controlled this resource would yield immense power in the coming years. D’arcy was hoping to position himself in that market.

The D’Arcy Concession and Early Explorations

In 1901, William D’arcy signed an agreement with Mozaffar Al-din Shah. There, he received the exclusive rights to explore for oil within a large area of southern and southeastern Persia. In Return, the house of Qajar was given 20,000 pounds and a promise of 16% of all future profits.

D’arcy hired a team led by George Reynolds to explore vast fields of the country. To find potential oil fields in the region. But finding oil in Persia soon proved easier said than done.

Iran’s southern and southeastern regions were not known for their hospitable conditions. These regions were under the rule of clans and nomadic tribes that were generally unwelcoming to foreigners. The temperature in these areas soared to 50 degrees Celsius during the day and dropped to freezing temperatures at night. With vast desert areas, finding water posed a significant challenge and was often deemed nearly impossible.

Despite these odds, Reynolds persisted with his task. He spent the next 4 years, searching every bit of the region for potential oil fields.

Initially, D’arcy was eager to spend his fortune on Reynolds and his expeditions, viewing it as an initial investment toward even greater wealth. However, by 1904, both the team’s luck and D’arcy’s finances were beginning to dry out.

The Search for Persian Oil: Reynolds’ Persistence

In 1904, desperate for cash flow, D’arcy was forced to sell a majority of his rights in Persia to Burmah Oil, a wealthy British oil company and a major player in the global oil industry.

By 1908, over half a million pounds had been invested in the Reynolds’ expedition. Yet the team had failed to uncover any promising leads.

Disappointed by these results and left without hope, the partners ultimately decided to give up their search in Persia and redirect their efforts to other regions.

In May of that year, the team sent a telegram to Reynolds informing him that there were no more funds to be spared. The telegram demanded Reynolds to cease all work. To let go of the staff, get rid of anything not worth the cost of transport and head back home.

Reynolds had spent the last decade navigating the harshest deserts of Persia for what he believed had the potential to change the future. He was not going to give up the task so easily.

Reynolds contended that he could not trust the accuracy of telegrams in the remote regions where he was situated. Therefore, he insisted that the team continue their work until the request could be confirmed through another, more reliable source.

The Discovery at Masjed Soleyman

By the end of May, while waiting for confirmation, Reynolds’s team set up camp in the western part of the country.

Masjed Soleyman was a city located in the Khuzestan province of Iran. It had a history that dated back to the ancient Mesopotamian empire of Elam. The city boasted numerous archaeological ruins, including an Achaemenid palace and an ancient fire temple attributed to the legendary pre-historic king Houshang.

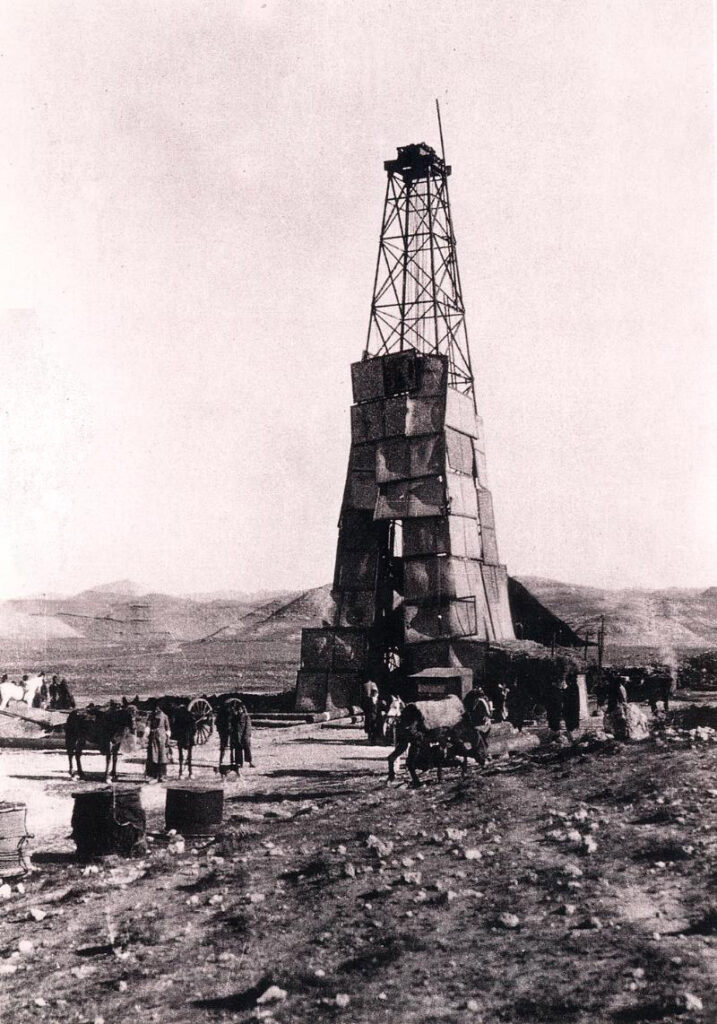

Reynolds’s team had set up multiple derricks in the region as a last attempt to hit oil before their eventual dismissal by the British. On May 26th, 1908 at roughly 4 in the morning, Reynolds was woken up to rambling shouts echoing in the region. He got up and left his tent; only to be met with a mountain of oil spurting above the derricks.

It was more oil than he had ever seen in his life.

It was the greatest oil field the British had ever found.

Russian Revolution: A Power Vaccum in the Region

In 1917, after the collapse of the Russian empire, there was a vacuum of power created in the Persian region. For the past century, Russia and Britain had been a permanent presence in the north and south of Iran. Although initially rivals, these two superpowers had come to an understanding to break Iran into two spheres of influence. The 1907 agreement between the two countries gave control of northern Iran to the Russians and the southern part, especially south-east to the British.

After Reynolds’s discovery, the British investors, realizing the high potential of Persian oil fields, organized a new business entity. The Anlgo-Persian Oil Company quickly absorbed D’arcy’s rights and took control of the entire oil operation in the region.

The Rise of Anglo-Persian Oil Company

Masjid-Solei-Maan’s wells produced around 900 barrels of oil per day. A significant amount at the time and it wasn’t the only active oil field in the country.

After the discovery, The Anglo-Persian Oil Company or APOC continued to drill in other parts of the region. Soon made additional discoveries, which confirmed that Iran had vast oil reserves. These reserves were soon recognized as some of the largest in the world. Thus, Persia became a major player in the global oil industry.

Five years after the Reynolds mission, the British government bought a 51 percent stake in the APOC for the price of 2 million pounds and became a majority owner of the corporation.

The buyout was championed by the then-first lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. Churchill understood the crucial role of oil in the future of military operations. With a looming threat of a global war on the horizon, Churchill recognized the necessity of securing a reliable source of oil to power the British fleet.

The British were hoping that access to Persia’s vast oilfields would bring them a unique advantage in this critical time and boost their superior naval fleet in the region.

Abadan: The Heart of Anglo Persian Oil Company

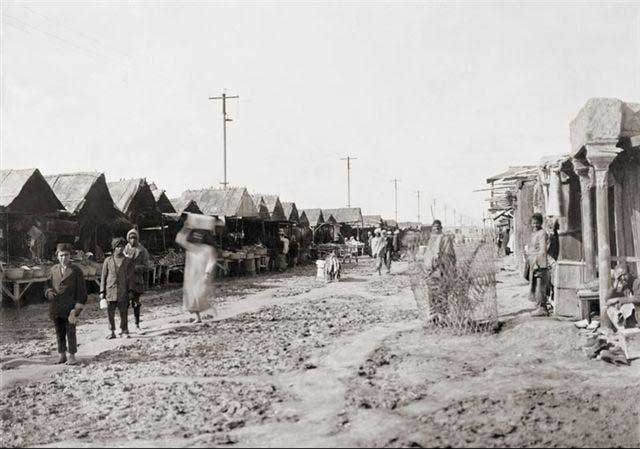

Abadan was a city located in the Khuzestan province of Persia located on the northern side of the Persian Gulf. The city bordered the Ottoman Empire and it quickly rose to become a central hubspot for the British government in the region.

In 1909, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company dispatched R. R. Davison to explore the area and initiate the process of building an oil refinery. Despite Davison’s initial report describing Abadan as a place of “Sun, mud and flies”, thousands of local people were soon hard at work constructing the necessary infrastructure to transform this barren land into the heart of the British oil industry. By 1911, the first pipeline had been completed, and by the following year, oil was flowing into the city. The development of the Abadan refinery marked a major milestone in the history of the global oil industry. It played a significant role in shaping the political and economic landscape of the Middle East in the 20th century.

Abadan quickly grew into one of Iran’s busiest cities, with a population of over 100,000 residents. However, the city was divided into distinct zones: one reserved for British workers and another, less developed area for the local population. The British workers lived in luxurious homes with breathtaking views of the city, manicured lawns, and every imaginable luxury at their disposal. Meanwhile, the Iranian quarters were marked by a stark lack of even the most basic commodities necessary for a decent standard of living. The Iranian workers were not permitted to enter shops, cinemas, or even ride on the same buses. They became second-class citizens in their own country. Forced to endure a life of hardship and deprivation while their British counterparts enjoyed the spoils of their labour.

Military Forces in Persia: A Three-Way Split

When the First World War started in 1914, Britians knew that Abadan and other oil cities would be a prime target for the central powers, so they decided to increase their military presence in the region.

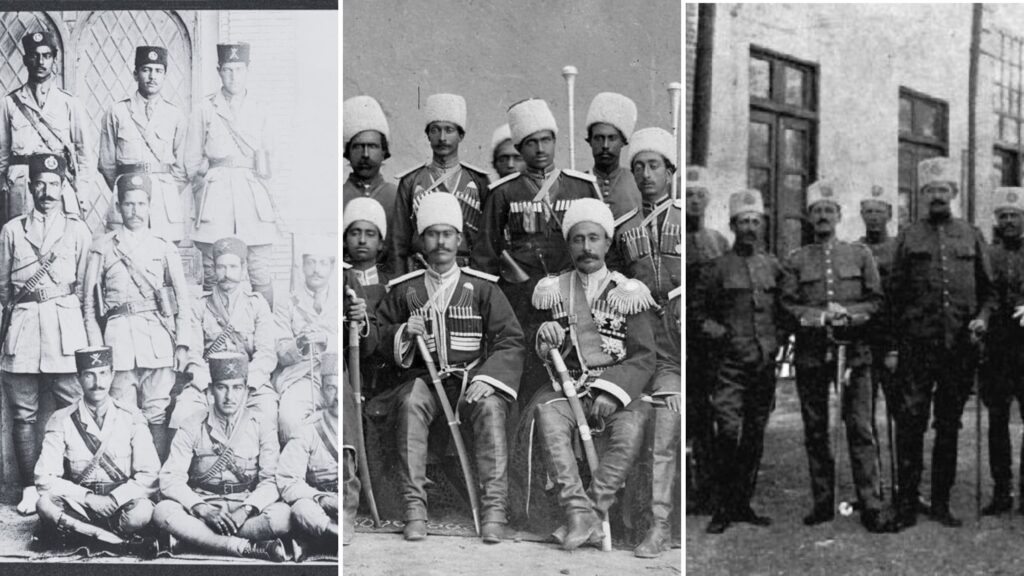

During his tenure, Wiliam Shuster, the American Treasurer-General, had noticed the weak state of Iran’s military and rural police. These forces were understaffed, inadequate and beholden to the interest of foreign powers. He had proposed the creation of a Treasury Gendarmerie. A paramilitary force that focused on collecting taxes from the distant parts of Iran. Neutral in its nature, the purpose of this force was the safety of Persian provinces, its pathways and far-out regions.

Shuster’s proposal was approved by Majlis and with the help of the Swedes, which Persians chose as a neutral middle between Russia and Britain, the Persian gendarmerie was founded.

The Many Armies of Persia

On paper, this branch of armed forces was supposed to be neutral. But during the First World War, officers of the Gendarmerie, like most of the Iranian intelligentsia and constitutionalists, were sympathetic towards Germany and were secretly helping the Central Powers.

The British knew that they couldn’t count on the Gendarmerie to protect their assets. So they decided to bring their own army to the region.

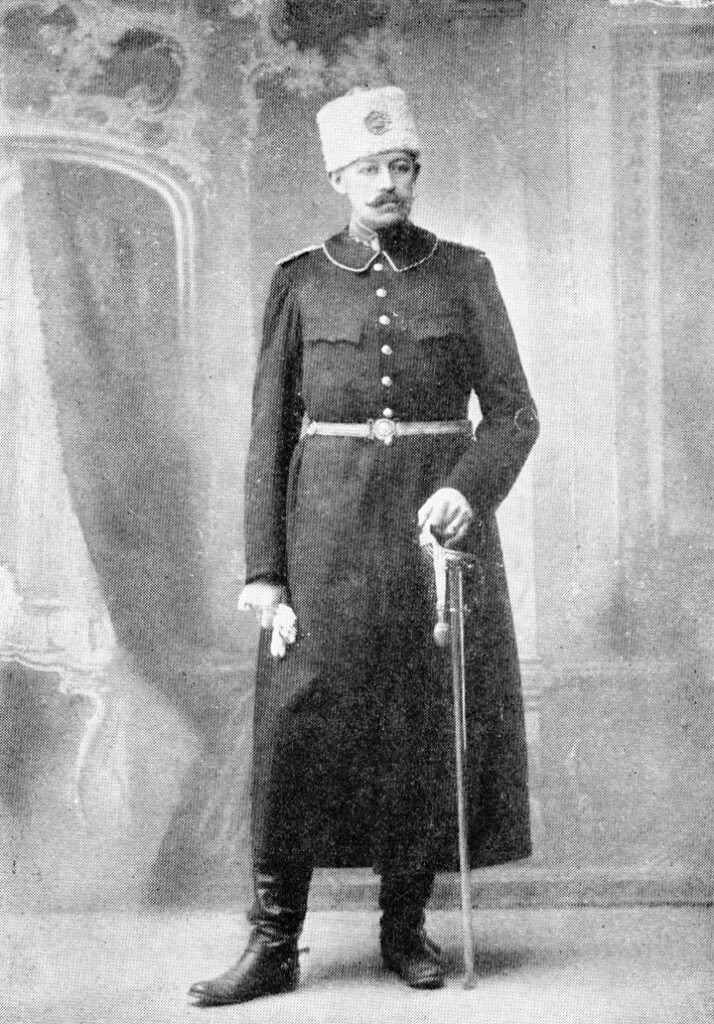

In March 1916, Percy Sykes landed in Bandar-Abbas. Percy Sykes was a British soldier, diplomat, and scholar, known primarily for his work in Persia. He had extensive knowledge of the region and had travelled to the country on multiple occasions. He had even written a two-volume book on the history of Persia. That’s why the British saw him as the perfect option for establishing a military base in the region.

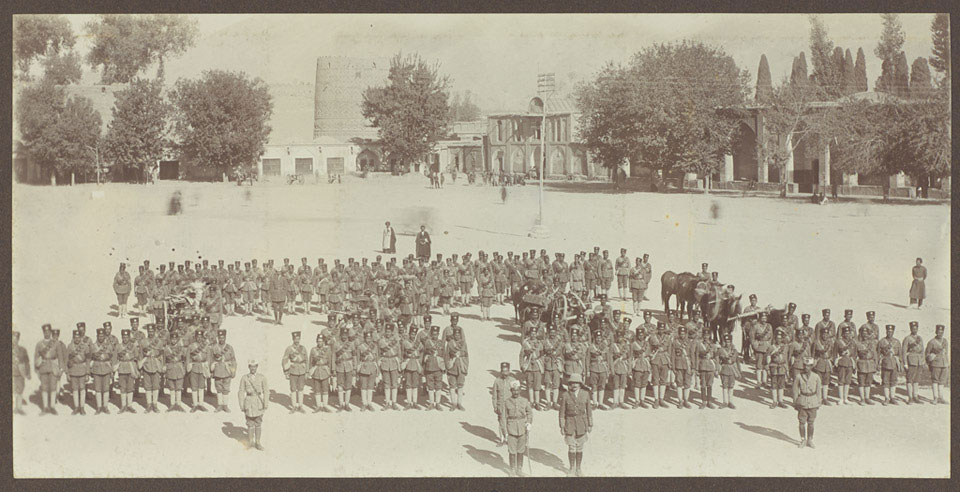

Upon his arrival, Skyes had a few British officers, a company of Indian soldiers and small quantities of weapons and ammunition at his disposal. His mission was to recruit and train a British-controlled army in Persia. The purpose of this army was to stand against Germany’s meddling in the region and to fight the local tribes and clans that were loyal to the central powers.

Sykes’s early recruits came from pro-British tribes but soon their army began welcoming soldiers from other British colonies, most notably, soldiers from the British Indian Army.

South Persia Rifles: A New British Military

By the end of the year, South Persia Rifles or SPR had brigades in numerous cities and their numbers had risen to 3,300 infantry, 450 cavalry and some artillery pieces and machine guns.

In 1917, The Rifles began a campaign to suppress any rebellious tribe within the vicinity of British interest. They went after them in their strongholds as well as their crops and livestock, crippling them logistically so they could not continue to raid British supply lines and garrisons.

During this time, Sykes also gained formal recognition for the Rifles from the Iranian government.

Gradually, the SPR operated throughout the region, stretching from the southwest border with British India to the Kerman, Fars, Khuzestan, and Bakhtiyari lands in the west.

At this point in history, Iran had 3 different forces roaming its land. The cossack brigade which was under the influence of the Russian Empire. The Gendarmerie, a supposedly neutral force that leaned more towards the Germans. And the South Persia Rifles which were loyal to the British.

The Fall of Russian Influence and British Expansion

After the fall of the Russian empire, the cossack brigade lost their biggest benefactor and financial supporter. Moreover, all of the Russian dispatches in Iran that were loyal to the fallen empire, were denounced by the new regime. The Bolsheviks even sent out their Red Army to hunt these remnants of the White Army. The Russian forces loyal to the tsarist Russia.

Britain, noticing the disarray of the White Army and the Cossack Brigade’s financial plight, saw an opening to increase their presence in Persia.

In late 1917, they established the North Persian Force, a new military unit aimed to support the stranded Russian soldiers and bring the Cossack Brigade under its wing.

Britain was worried that the northern influence of the Bolsheviks, might threaten their supremacy in the region. They weren’t sure that the armed forces in the upper parts of Persia could protect their interests. Their worries soon proved to be more than justified.

Jangal Movement: A Socialist in the North

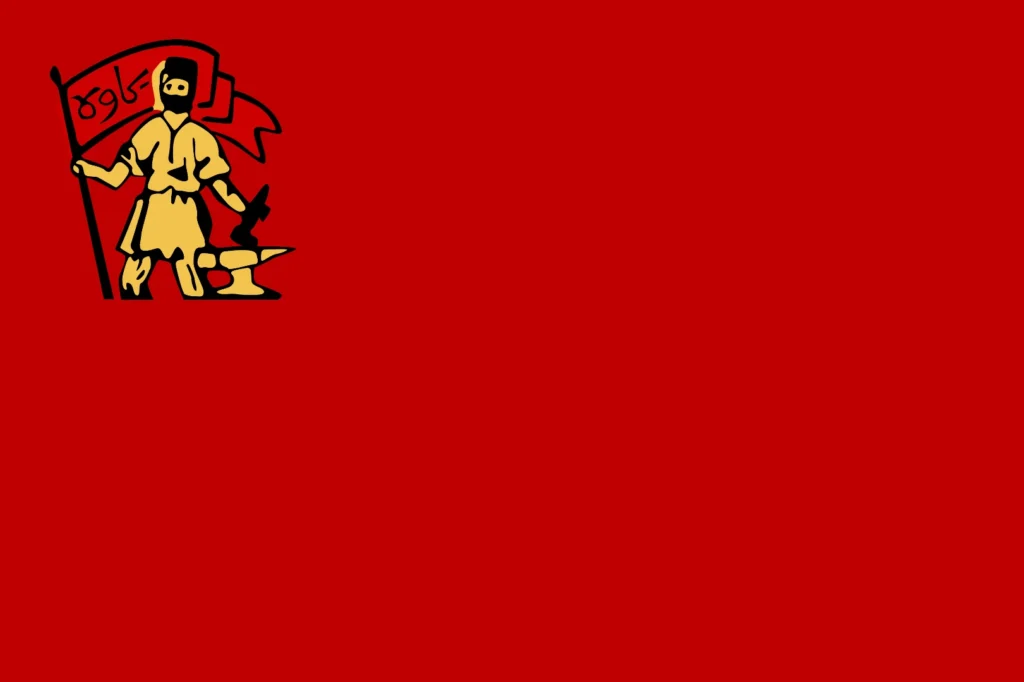

Mirza Kuchak Khan was born in the city of Rasht. In 1905, while a seminary student, he was inspired by the message of the constitutional revolution and decided to devote his life to this cause.

In July 1911, he fought against the deposed Mohammad ‘Ali Shah’s coup attempt. This ended in his wounding and capture by Russians. Upon his release, he returned to Rasht. There he became an anti-Russian activist, and contemplated organizing a partisan war in the forests of his homeland.

Despite limited support, Kuchak Khan mobilized a small guerrilla force of like-minded individuals. The movement quickly grew, attracting peasants, artisans, shopkeepers, and former revolutionaries.

Kuchak Khan was described as handsome, charismatic, and witty, yet also irritable and mythical. He dressed in a local Gilan outfit and was seen as a romantic figure, blending anti-imperialism with a socialist flavour and new interpretations of Islam as an anti-colonial force.

Before 1917, the Jangal movement, founded by Mirza Kuchak Khan, was a minor irritant to Russian forces and local collaborators in Iran. They engaged in ambushes, looting, and extorting from landlords and merchants to protect peasants from oppression.

However, the movement gained new life after the Bolshevik revolution. After the fall of the White Russian resistance and with the backing of the Red Army, the Jangalis hoped to use their momentum to inspire a socialist revolution in Iran. They even declared a Soviet Republic in Iran known as the Gilan Socialist Republic.

During this time, a rift in ideology became apparent in the movement. Mirza Kuchak Khan was a nationalist with Islamic sentiments. But with the support of the Bolsheviks, his movement was tilting toward a strong socialist ideology.

The Aftermath of Kuchak Khan and the Jangal Movement

In the aftermath of declaring the Gilan Socialist Republic, Kuchak Khan was relegated to a ceremonial role in the movement and other — more socialist — members took control.

Using this newfound support and standing against the involvement of Britain in Persia’s affairs, the Jangalists decided to expand their influence.

In June 1920, with the help of the Red Army, the group took control of Rasht, repelling local forces and British troops.

The central government, pushed by the British, deployed the cossack brigade to take back the city. Their army met a crippling defeat and was forced to retreat. The members of the movement, galvanized by this victory decided to expand their presence and set their sights on Tehran.

Despite the Jangal-Bolshevik alliance’s gains and the Tehran government’s inability to quash them, an internal coup against Kuchak Khan weakened the movement. Finally after numerous assaults on the city, the government was able to push back the Jangalis back into the northern forests of Iran.

With a fractured leadership, lost ground and weakened forces, the movement that had become the only remaining hope of Nationalists, faded into obscurity.

Curzon’s Vision for Persia

While Britain’s official reason for increasing its presence in the region was to counter Bolshevik influence, bolstered by the rise of the Jangal movement, the true intent behind Britain’s actions was far more complex and strategically calculated.

George Curzon was a prominent British statesman and a key figure in British Imperial policy. Curzon’s political career began in 1886 when he was elected as a Member of Parliament.

His dedication and expertise in foreign affairs led to his appointment as Viceroy of India in 1899 and ultimately as the foreign secretary of the British Empire.

Curzon viewed Iran as a pivotal stronghold in the Middle East, crucial for protecting British interests in the region. He was convinced that Iran’s security required British involvement. Additionally, establishing a presence in Persia would create a contiguous land network. Linking India, Persia, Iraq, Egypt, and ultimately, the British Empire.

That is why the prospect of a new Anglo-Persian agreement seemed like the perfect opportunity for him. He wanted to exert the might of the British into this land. A land that, until now, had managed to retain a semblance of independence.

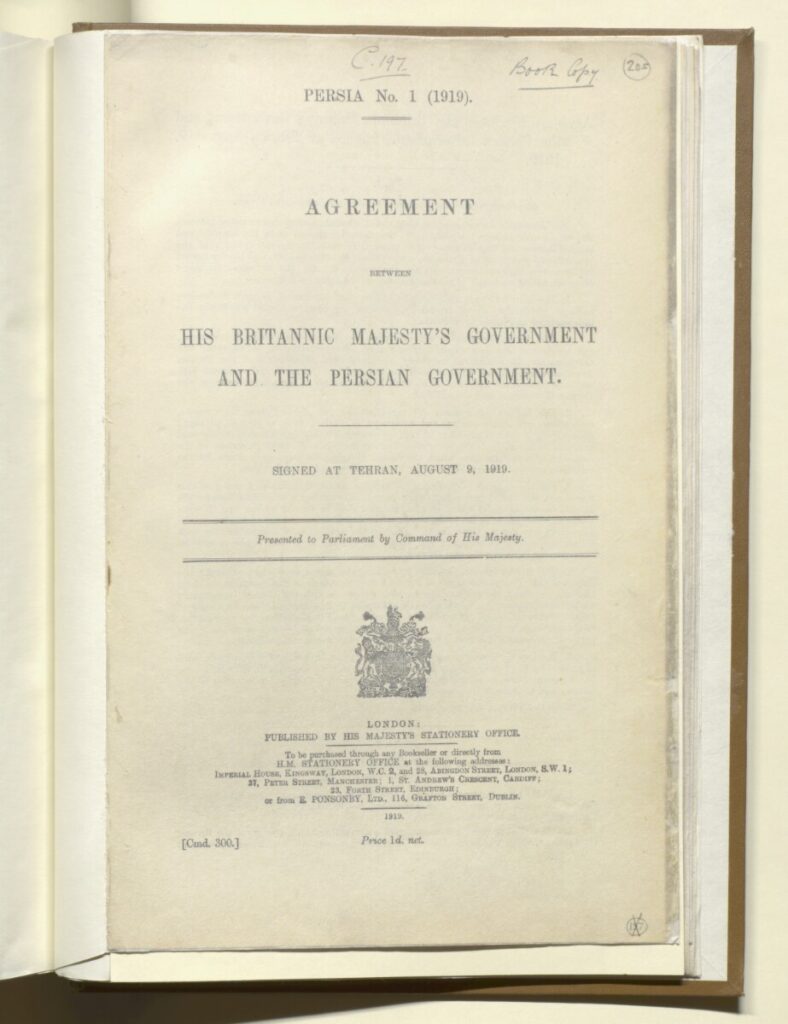

The Anglo-Persian Agreement of 1919

The agreement was first ideated by Percy Cox, the British envoy in Tehran. Cox, much like Curzon, understood the importance of Iran in safeguarding Britain’s assets. He saw this as an unofficial way to give Iran a British protectorate status.

A “British Protectorate” was a type of colonial rule used by the British Empire. Where a region or territory was governed or overseen by the British without being directly administered as a part of the empire. In a protectorate, the local ruling structure was typically left intact. But the country was expected to follow the directives of British advisors on issues such as foreign affairs and defence.

Up until then, due to the existence of the Russian empire and their rivalry with Britain, Iran was seen as a buffer zone. The Anglo-Russian agreement of 1907 divided the country into two spheres of influence. But now, Britain wanted to have complete control of Iran’s internal affairs.

On the surface, the 1919 agreement was about mutual collaboration and partnership between the two nations. It promised British financial, technical, and military assistance to Iran. In return for Iran’s exclusive reliance on Britain in areas like defence and foreign policy.

The agreement highlighted the “ties of friendship” between the two nations. It expressed a commitment to the “progress and prosperity” of Persia. It also categorically affirmed the independence and integrity of Persia.

The World Responds to the Agreement

While the agreement emphasized Iran’s independence, deep within its articles, laid the foundation of control and decay. This agreement essentially allowed the British to assume full control over certain aspects of Iran. With a significant focus on the oil resources that were being extracted by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. It sought out Iran’s revenues and customs as collateral for loans given to the Persian government. It also forced the hiring of British financial and military advisers at the expanse of Iran.

The agreement was so intrusive that even The United States criticized its existence. The US viewed it as a means through which Britain acquired colonial powers in Iran.

The international world worried about Britain’s appetite for devouring another independent state. But inside, the Persian government embraced the idea of a closer partnership with the empire.

Hasan Vosuq al-Dowleh, Iran’s then grand-vizir, saw the 1919 agreement as the only way to safeguard the country’s future. In his eyes, Britain’s expertise in military and finance could save Iran from its post-war spiral into chaos.

But despite the “official” support, the Persian populous stated a definitive opposition to the agreement.

The Death of the 1919 Agreement and Its Aftermath

The people, especially nationalists, were tired of foreign control. They saw the 1919 agreement as destroying Iran’s independence. Disdain for the agreement grew rapidly. Vosuq al-Dowleh was now called a traitor. He lost all social credibility. He became a hated figure in Persian politics.

The young shah, witnessing the wave of anger within its people, saw no choice but to dismiss Vosuq al-Dowleh in June 1920. After Vosuq al-Dowleh’s dismissal, it became clear to the British that the 1919 agreement was officially dead.

The cancellation of the 1919 agreement was a great win for Iranians. But the people knew that a few signatures wasn’t going to change the status of the land. With Britain controlling 3 of the 4 main military fractions of the country, Iran was destined to forever be under its control. Even if the influence was never ratified by the government and Majlis.

In 1920, Iran was a nation engulfed in the aftermath of war, its cities haunted by death and famine. The constant turnover of key government officials rendered any lasting improvements a distant dream. The unofficial military occupation, along with rampant gangs and looters, turned everyday life into a relentless struggle for survival.

However, the next year brought about a momentous change. Iran, desperate to escape its plight, was on the verge of a historical transformation.

On a cold winter morning, as the people of Persia awoke, they found themselves in a brave new world with the destiny of their country, forever changed.

5 Responses