This is the transcript for Book One, episode 9 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: The Coup about the rise of Reza Khan and how became Iran’s minister of war. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

An Ominous Message

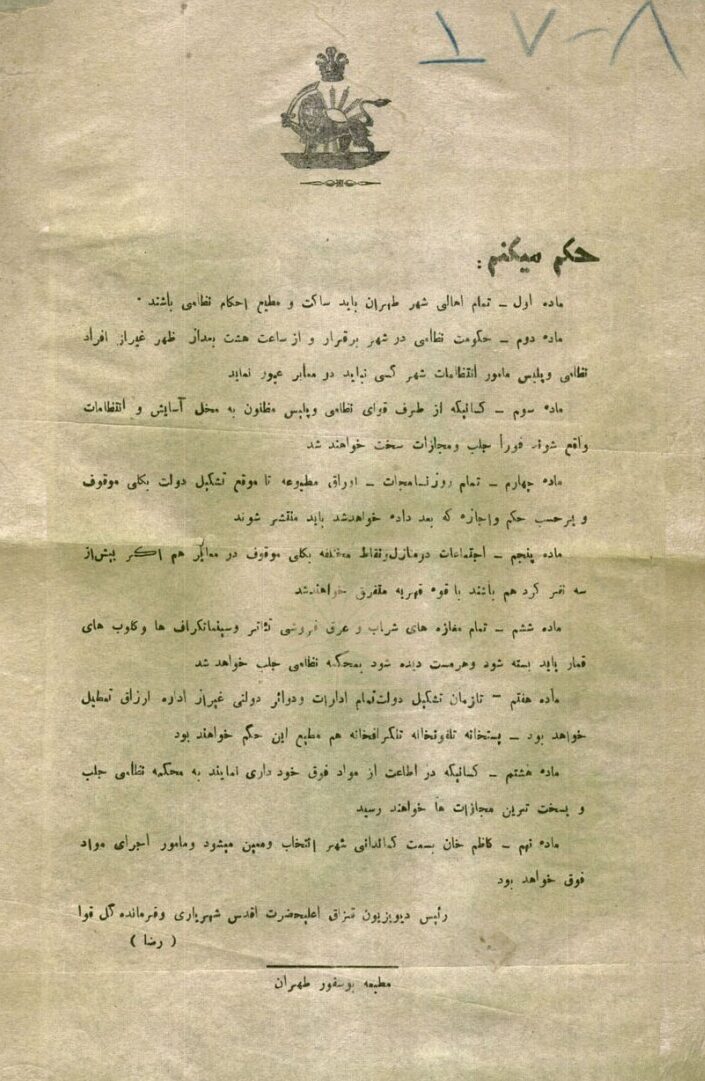

“I Command” The poster read.

The title was confusing but the fine written text under it gave context to the ominous communication. A message that defined the next evolution of Persian politics and changed the trajectory of the country forever.

February 21st, 1921 began like any other, with winter’s chill deepened by a brisk breeze and overcast skies.

A City in Transition

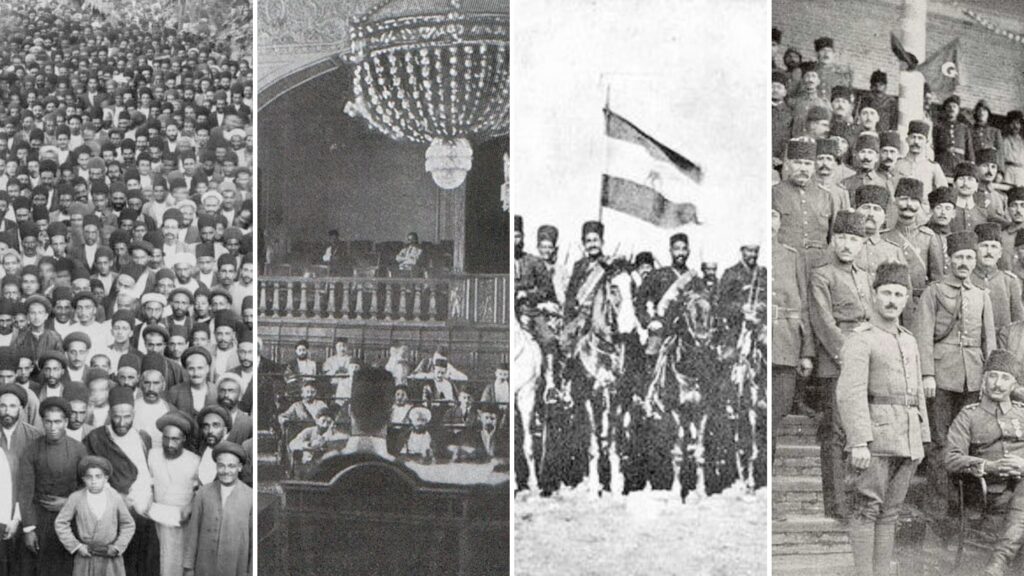

Tehran, within a brief span, had witnessed monumental changes. A constitutional revolution, the establishment of a parliament, a civil war, a world war, and the constant threat of foreign invasion. The city had become a shadow of what it once was. Its people grapple with the challenges of daily survival. A monarchy anxious about the potential fall of their long-standing dynasty.

If you had asked any ordinary person in the city, they would have said that they’d seen everything there was to see. But to their surprise, their shared memory was about to become even more complicated.

As the hours passed, the people of Tehran began their usual routines. They woke up, ate their food and headed out to work … where an unexpected sight awaited them.

Positioned prominently near the main thoroughfare, the notice initially caught the attention of only a handful of early risers. Their curiosity piqued, they congregated around the placard, their eyes scanning the printed words. The growing cluster of onlookers soon attracted others

A few moments later, word of mouth began to spread. Soon, everyone was talking about it.

Martial Law in the City

The directive was unambiguous, its terms non-negotiable. It declared that the residents of the capital were to adhere strictly to a new set of military mandates. This decree effectively imposed martial law upon the city. Nullifying all previously granted permissions. Outlawing any form of public assembly, and imposing a stringent ban on the of news through any medium.

The notice ended with a warning:

“Those who fail to obey the given orders shall be met with harshest of punishments.”

Tehran, along with the government and the entire country, found itself in the grip of a military coup. Led by a political journalist. Supported by a young military general, whose signature had officially sanctioned the martial law order.

“Reza, Head of Cossack Division and Military Commander of the Capital”

The Aftermath of World War I

The occurrence of the First World War was a consequential event that changed the trajectory of history. A period of great industrial development that reshaped the landscape of Europe. Its ramifications echoing in every corner of the world.

The formation of the League of Nations which was a precursor to the United Nations. Establishment of the Treaty of Versailles, imposing heavy reparations on Germany. And finally, the collapse of several major empires like the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, German, and Russian Empires were only some of the key events caused by this global phenomenon.

World War 1 led to the formation of the League of Nations, a precursor to the United Nations, the establishment of the Treaty of Versailles, which imposed heavy reparations on Germany, and the collapse of several major empires, including the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, German, and Russian Empires.

Yet while the world was recovering and healing in the aftermath of the war, one nation descended further into turmoil, hardship, and crisis.

Post-War Chaos in Persia

The post-war period in Persia was the embodiment of chaos. With the emergence of the Gilan Socialist Republic, the increasing influence of the Qashqa’i tribes in the West, and ongoing conflicts in the east, the idea of a fragmented Iran seemed increasingly plausible.

During this time, Iran had four different armies, numerous tribal forces independent of the government, and countless gangs preying on the routes and streets, making life even harder for the people.

Additionally, the government struggled to maintain a stable cabinet. In the 15 years since the constitutional revolution, 51 cabinets had come and gone. In recent years, the grand vizier or prime minister could barely keep the government together for months before either resigning or being replaced. The national assembly, or Majlis, now in its fourth iteration, couldn’t even hold an inaugural session due to the heated differences among its many factions and coalitions.

The ongoing crisis had soured the taste of democracy in the minds of Iranians. People had seen nothing but misery since they aspired to modernization and freedom. They believed their lives were much better under the absolute rule of Nasir Al-Din Shah. Some wouldn’t have minded turning back the clock to relive those days.

This alarmed the young monarch. Ahmad Shah feared facing the same fate as his father. He was worried about losing control over the country he ruled. His anxiety was exacerbated when the British announced their plans to withdraw significant portions of their military from the country.

Britain’s Strategic Retreat

After World War I and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the League of Nations mandated Britain to oversee parts of the now-collapsed empire until they were ready for self-governance. In Iraq, from 1920 to 1932, Britain’s mandate focused on establishing a political structure, defining borders, and developing the oil industry, while managing ethnic and religious diversity and local resistance. In Palestine, the mandate (1920-1948) centred on implementing the Balfour Declaration, which promised a homeland for the Jewish people while respecting the rights of non-Jewish communities.

These mandatory commitments were draining Britain’s resources, and with opposition in the House of Commons, Britain was looking to scale down its operations in the regions including reducing their armed forces in Persia.

Despite this reduction, they were well aware of Persia’s significant leverage. From its vast oil fields to its strategic positioning near India, Britain had to find a way to maintain its influence. That is why the plan of a young journalist became very interesting to them.

Sayyed Zia: The Rebel Journalist

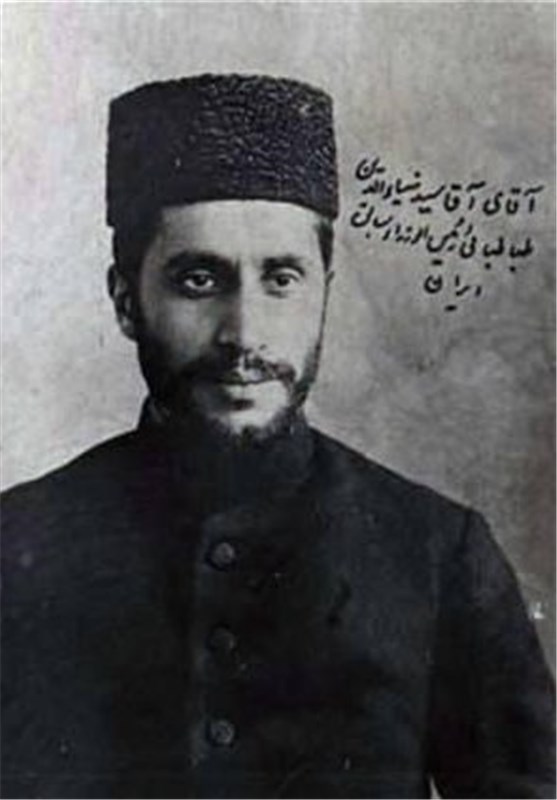

Sayyed Zia al-Din Tabataba’i was a fierce journalist. An ambitious political activist who yearned to mark his mark on the Persian political stage.

Born in 1888 in Shiraz, Iran, into a prominent clerical family, Sayyed Zia’s early life was characterized by a blend of religious upbringing and secular education.

In Tehran, Sayyed Zia established himself as a fervent journalist and an advocate for political change. He utilized his writings to criticize the autocracy of the Qajar dynasty. He called for the establishment of a constitutional monarchy. His editorial work, especially for the newspaper Raʾd (“Thunder”), focused on criticizing the autocracy of the Qajar dynasty and to call for the establishment of a constitutional monarchy

Building British Connections

Sayyed Zia was mentored by Vosuq al-Dowleh, the previous prime minister. He was also used as his proxy to advocate the ratification of the 1919 agreement. As mentioned in the previous episode, the 1919 agreement between Britain and Iran, was intended as a mutual collaboration and partnership between the two nations. While the agreement outwardly emphasized “ties of friendship” and Iran’s independence, it essentially allowed Britain to assume control over significant aspects of Iran, particularly its oil resources.

Sayyad Zia’s advocation for the agreement helped strengthen the relationship between him and the British government. Even after Vosuq al Dowleh was removed from his position, he remained in contact with the British.

Other Players in the Capital

Sayad Zia was in the midst of formulating a strategy to rescue Persia from chaos and stabilize its crumbling government. During this time, he wasn’t alone in considering a coup to shift the country’s power dynamics. With diverse factions spread throughout the land, including government armies and local tribes, there was a lack of unified vision among those disenfranchised by the existing regime, sparking simultaneous calls for change from various quarters.

Among them were Hassan Modarres, a parliament member and staunch anti-Russian activist during the world war, and Sardar Assad Bakhtiary, who led the southern army in the battle of Tehran.

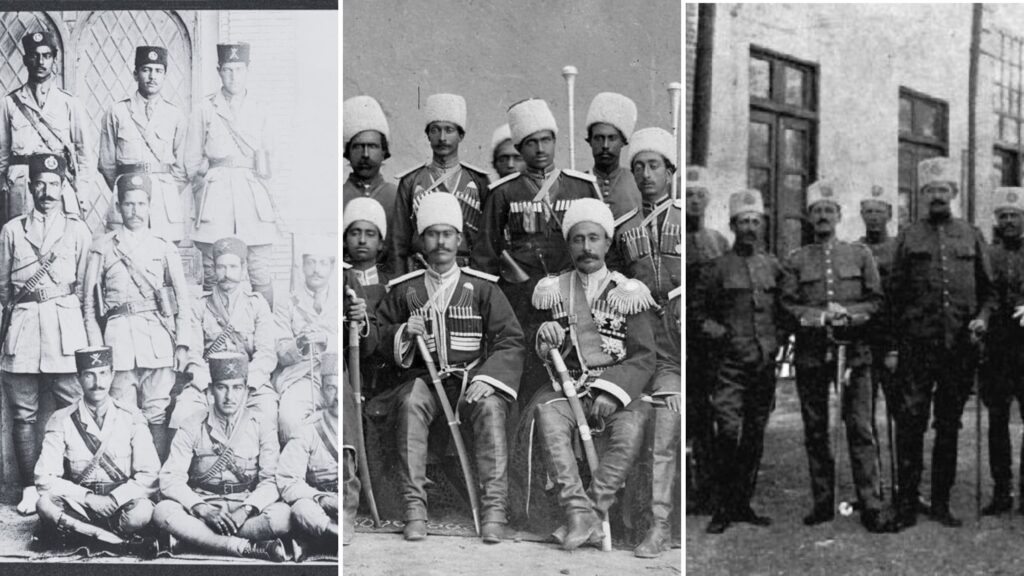

However, Sayad Zia possessed a critical advantage: successful coup execution and government control required army support. At that time, Iran lacked a centralized military force, making Cossack Brigade the most powerful force of the country. This Russian division, tasked with protecting the king and now under British control after the collapse of the Russian Empire, was key to success.

The British, who had forged a strong relationship with Sayyad Zia al-Din Tabataba’i, were reducing their regional presence and preferred not to engage directly in a potentially costly and perilous coup. Nevertheless, they recognized that a stable Persian government would protect their interests and provide relief. Therefore, they were inclined to support Sayyad Zia’s ambitions indirectly. They knew the perfect man able to facilitate Sayyad Zia’s plan.

Reza Khan’s: A Soldier from North

Reza Khan’s early life was marked by hardship. Born on March 15, 1878, in Alasht, Mazandaran Province in the north of the Country, he lost his father just a few months after his birth, leading his mother to move the family to Tehran.

At around 15 years of age, Reza Khan joined the Cossack Brigade, a military unit under Russian instructors, where his leadership qualities and military skills quickly became apparent. By 1911, he was promoted to first lieutenant, and his military career progressed rapidly from there. He was known for his strong will, intelligence, and a capacity for leadership. These have even earned him a high regard among his superiors and peers alike.

He was tall and broad, had a commanding presence and according to those who got to know him, was charismatic. But most importantly, Reza Khan was extremely ambitious

Reza Khan’s Rise through the Ranks

By 1918, Reza had become a colonel in the Cossack Brigade which was now known as the Cossack Division. This reclassification was a strategy by the British to downplay the military force as less formidable. After World War 1, sensing the shifting tides of power, he had titled towards the british. He had helped them with ridding the army of its Russian leadership. He knew that the British were now in control and if he wanted to reach his aspirations, he had to align himself with them.

Reza khan was also worried about the state of his country. The Cossack Division’s initial defeat by Jangal forces convinced him that without intervention, Iran was at risk of succumbing to Bolshevik influence. Determined to prevent this, he sought to enact change and safeguard his country before it was too late.

As mentioned, not much is known about the role of the Britain in the coup of 1921. What it is known is that the British wanted stability in the region. They knew about Reza Khan’s potential and Sayyad Zia’s plan for reform. Shortly afterwards, these two individuals were put on the same trajectory.

The Day of the Coup

“I Command” The poster read.

February 21st, 1921 began like any other, with winter’s chill deepened by a brisk breeze and overcast skies. But soon the people of Tehran were met with an unexpected announcement distributed across the city.

The directive was unambiguous, its terms non-negotiable. It declared that the residents of the capital were to adhere strictly to a new set of military mandates. This decree effectively imposed martial law upon the city. It nullified all previously granted permissions, outlawing any form of public assembly. It also imposed a stringent ban on the dissemination of news through any medium.

At first, the edict was met with skepticism. Both the elite and ordinary citizens dismissed it as yet another exploitative move in Iran’s chaotic political landscape, lacking any real substance. But as the day continued, the gravity of this movement dawned on the people.

Three days earlier, an army consisting of four thousand cossack soldiers, under the command of Reza Khan departed Qazvin to head for the capital. Near the city Reza Khan and Sayyad Zia had met. On the early hours of February 21st, the army began the occupation of the capital.

A Bloodless Takeover

By global standards, the coup of 1921 was a relatively fast and bloodless one.

The Cossack division had entered Tehran with little to no resistance. Both the Gendarmerie and Tehran police force had surrendered without a fight. The occupying forces were stationed in the city; where they began arresting high-ranking government statesmen and Qajar nobels.

The arrests were a fear tactic, designed to shock the city and emphasize the military aspect of the movement.

And the threat worked.

A few days after the coup, Ahmad Shah who was afraid that his resistance would lead to his own removal from the throne gave in and was convinced by his advisers and close circle to make the hard decision. He agreed to remove his grand-vizir from the post and appointed Sayyad Zia as the new prime minister. The first person to be selected from this position was outside of Qajar nobility and elite. He was one of the people.

The New Prime Minister’s Vision

On February 25, Sayyad Zia Al-Din Tabatabaei published his very first announcement as the new prime minister of the government. This communication was similar to a road map of Sayyad Zia’s vision for the country. He justified his resort to force and coup as a necessity after the betrayal of sacrifices made by the people. Zia believed that the government had failed to protect the ideals of constitutional revolution. He wanted to change the nation’s path.

Sayyad Zia’s statement had a populist tone. It appealed to the people’s sense of nationalism to gather support and strengthen his position.

The Shift Towards Nationalization

We should keep in mind that in the early 20th century, this nationalism wasn’t just limited to Iran. All over the world, countries were experiencing a shift toward patriotism and national pride. From the German empire that was founded on the basis of Germanic identity, to the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, which marked the rise of Soviet nationalism under the guise of spreading communism and unifying diverse ethnic groups under a single state and Turkey, where the fall of the Ottoman Empire led to the establishment of the Republic in 1923 under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, driven by Turkish nationalism and a push for modernization and secularization.

It’s important to note that early 20th-century nationalism wasn’t exclusive to Iran. During this period, a global shift toward patriotism and national pride was evident. The German empire was established based on Germanic identity. The Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 signalled the rise of Soviet nationalism. This revolution aimed to spread communism. It also sought to unify diverse ethnic groups under one state. In Turkey, the fall of the Ottoman Empire led to the creation of the Republic in 1923. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk led this establishment, fueled by Turkish nationalism. Atatürk’s leadership also emphasized modernization and secularization.

All over the world, people were clinging to their national identity as a unifying factor. Sayyad Zia planned to do the same in his statement to the people.

Wasted Potential: The Downfall of Sayyed Zia

Zia criticized elitism and governance resembling European feudalism, which favoured landowners and nobility over the common people. While focusing on national security, improving domestic revenue, and raising the standard of living for working people. He vowed to fight against the high inflation, food shortage and improve the state of Iranian cities, especially the capital.

In terms of foreign policy, Sayyad Zia adopted a cautious approach, advocating for Persia’s peaceful coexistence with its neighbours while ensuring they did not interfere in the nation’s internal affairs. He later criticized the 1919 Anglo-Persian agreement as detrimental to Persian interests, backtracking his initial support for the treaty a few years earlier.

But despite these early achievements, Sayyad Zia was doomed for the destiny he had fought to overcome. Just like all the other prime ministers before him, the honeymoon period of his government soon come to pass. By alienating all the country’s elite and Qajar nobles and having a tarnished reputation amongst the working class due to his closeness to the British, Sayyad Zia had lost the popularity contest on every front. Soon the British discovered that having a man loathed by both the upper and working class was not so useful in keeping peace and stability in the region and withdrew their support of this reporter-turned-politician.

On May 25th, 1921, after a verbal argument with Ahmad Shah, Sayyad Zia was removed from his position and was banished from the country. Sayyad Zia aspired for greatness and wanted to lead the country to a brighter future, but with the dark stain of coup and mass arrests, his short tenure amounted to … almost nothing.

Three Armies: A Scattered Military

While Sayyad Zia’s entire cabinet was overshadowed by these events, there was one person who managed to emerge from the situation stronger and more popular than before.

After capturing the capital Reza Khan assumed the new title of Sardar Sepah, meaning the head of the army. In less than a year he gained control of the entire Cossack Division and soon, merged it with Iran’s local troops, Gendarmerie and the city police. Iran finally had a unified army and its control was in the hands of Reza Khan.

One of the first international actions of Sayyad Zia’s government was the signing of the Russo-Persian Treaty of Friendship, a mere five days following the coup. This treaty, which demanded the withdrawal of all Bolshevik forces from northern Iran, marked a significant milestone.

The Bolsheviks pulling out from the north, ending their backing of the Jangal movement, coupled with the departure of British forces, were all viewed as acts of liberation for the country. By this time, Reza Khan, who had risen to the position of war minister, was widely credited for these accomplishments.

With foreign influence gone from the lands of Persia, Reza Khan used his unified army to crush the local tribes that had been using the chaos to make life hard for the people and soon, peace was once again felt within the cities of Iran.

During this time, just like before the coup, no stable government was able to hold power for long. Famous for its “100-day” cabinets, this period consisted of people who came to power, attempted to exert change, failed to do so and were removed by Shah and replaced by someone else.

The only constant across all these “100-day” cabinets, was the presence of Reza Khan as the minister of war.

Reza Khan’s Power Consolidation

With a consolidated army of 150,000 at his command, access to 40% of the government’s budget, and being viewed by the public as the nation’s saviour, he emerged as the most influential figure in Iran, possibly even surpassing the Shah in popularity.

He was all that Sayyad Zia aspired to be and all that the British were searching for. He was someone who had the respect of both the nobility and the common people. Someone who could sway power and stabilize the region. But most importantly, he could be efficient, calculating and precise in his work.

Reza was acutely aware of his own capabilities. More than just a military general leading troops, he was strategic and pragmatic, and his ambitions soared higher. His influence outshined any temporary prime minister. That’s why in October 1923, when Ahmad Shah offered him the chance, he didn’t hesitate to step up as the country’s prime minister.

Yet, for Reza, that position was just a stepping stone.

He harboured even grander visions.

He wanted to be the unrivalled leader of his country, to awaken Persia’s full glory.

In the season finale of The Lion and the Sun, we’ll see how Reza Khan stages another coup, this time aiming for the entirety of the Qajar dynasty and how he becomes the undisputed ruler of his country.

5 Responses