This is the transcript for Book One, episode 10 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: Brave New World. This story is about the self-exile of Ahmad Shah and how Reza Khan’s attempt to establish a republic of Iran. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

Tehran: A New Vision

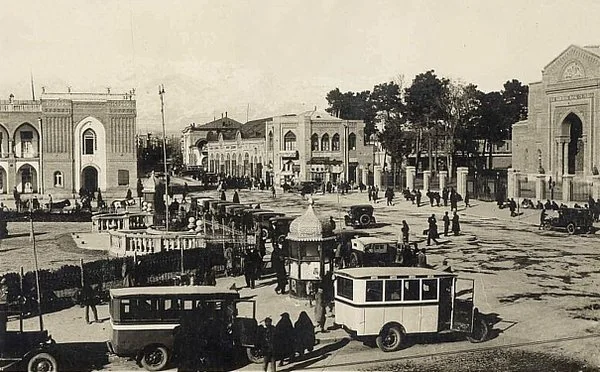

Tehran’s winters were known for being harsh and cold. The city, located at the foot of the Alborz mountain range, was often blanketed in snow. Temperatures would frequently drop below freezing. Despite being the capital of Persia for more than a century, by all standards, Tehran was still an underdeveloped city. With ancient brick houses, dirt roads, and a lack of electricity in most of its areas.

The city had recently undergone a period of modernization and westernization. This was reflected in its design as well; with a city citadel, civilian quarters and a marketplace for people to do business. None of these were up to the 20th century standards, however. The capital of Persia seemed like a city lost in time and locked in an ancient era long gone.

It was what many considered a work in progress.

For Reza khan, this barren capital of the Persian empire was filled with potential. Detached from the alliances of the north and south, far from foreign hands and prime for progress, the city was ready to be modernized. The only thing standing between the city and its rebirth was the people who controlled it.

An ancient monarchy on the brink of collapse, gangs devouring the neighbourhoods and their people, and corruption at every council and office. None of this was going to stop Reza, though.

He was a man with a plan

Nowruz: Symbol of Change and Rebirth

In Persia, the end of winter marks the start of a new year. This is celebrated with the traditional Persian festival of Nowruz, or “New Day.” This celebration marks the moment when the sun crosses the celestial equator. It signals the full passage of the Earth in its orbit around the sun and the official start of spring. Nowruz is a time for new beginnings, for coming together with loved ones, and for embracing change.

And on 1924, the biggest of these transformations was right around the corner …

Reza khan was an agent of change. He always prided himself in being able to get things done, despite the uncertainty and the hurdles. Reza knew what he was capable of and was ready to carry the weight of the empire on its shoulders. He was ready to bring Persia into the new age.

Tehran’s winters were known for being harsh and cold, but the dream of spring always pushed people forward. And in 1924, the dream was bigger than ever. The land of persia was ready to get rid of its monarchy. It was about to welcome democracy and join the free world.

The 1922 Wheat Shortage and Its Fallout

In October 1922, Tehran faced a severe wheat shortage, resulting in a lack of bread across the entire city. Wheat was a main part of the diet in early 20th-century Persia. Bread, made from wheat, was a staple food widely consumed by the population.

Wheat cultivation was significant due to its adaptability to Iran’s diverse climates and its ability to be stored for long periods, making it a reliable food source year-round. But in the fall of 1922, this widely available source of nutrition was gone from the capital.

The shortage was traced back to the army’s misuse of the state’s wheat supply. The blame fell on the man who controlled the entire Persian army and was Minister of War.

Over the past two years, Reza Khan had become a permanent presence in Iranian politics. From the coup that brought Seyed Zia to power, to crushing the Jangal socialist movement in the north, and even unifying the many factions of Iran’s army into a cohesive military force.

Political Uncertainty: “100 Day Cabinets”

From February 1921 to October 1923, there were numerous changes in the government. This mostly involved three main grand viziers or prime ministers. Mowshir al-Dowleh, Qavam al-Sal-Taneh, and Mostofi al-Mamalek kept switching roles every few months. They were hoping that the new prime minister would finally be able to establish a stable government, bring stability to the court, and calm the chaotic post-war landscape of Iran. Yet, month after month, they would fail, change roles, and repeat the process once again.

During all these turnovers, the only stable presence in all cabinets, regardless of the prime minister, was Reza Khan. After becoming the Minister of War, his success in the role made Reza an invaluable member of the cabinet. His savvy political maneuvering allowed him to exert his power and influence over all prime ministers and even the king himself.

Reza Khan’s Vision for Military

Reza wanted funds to modernize the military, recruit new soldiers, and manage ongoing campaigns. These campaigns included hunting down the remnants of the Jangal movement in the north, dealing with rebel tribes in the south, and securing the Persian roads long controlled by looters. The money for these expenditures came from indirect taxes and state income generated by Iran’s share in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, which amounted to 1 million pounds.

Reza Khan’s ambitions had turned military spending into the largest item in Iran’s budget. Reza’s persuasion and gravitas made it difficult for anyone to deny his demands. He was so adamant in his requests that Ahmad Shah once had to fake an illness to leave the country and avoid granting him more funds.

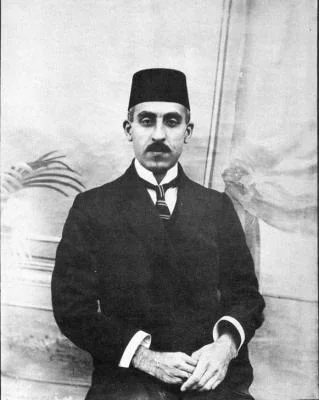

Not everyone was happy with Reza Khan’s reckless military spending. Iran was still suffering from the aftermath of World War I. Many believed that there were better ways to allocate these funds. One of these individuals was Mohammad Mosaddeq. Mosaddeq, a prominent figure whose story will be a significant part of later discussions, was the Finance Minister under Qavam al-Sal-Taneh. He opposed the military overspending and sought to negotiate a better budget plan with Reza Khan. However, as mentioned, Reza refused to back down from his demands, leading to Mosaddeq’s resignation in 1922.

Rising Opposition in Parliament

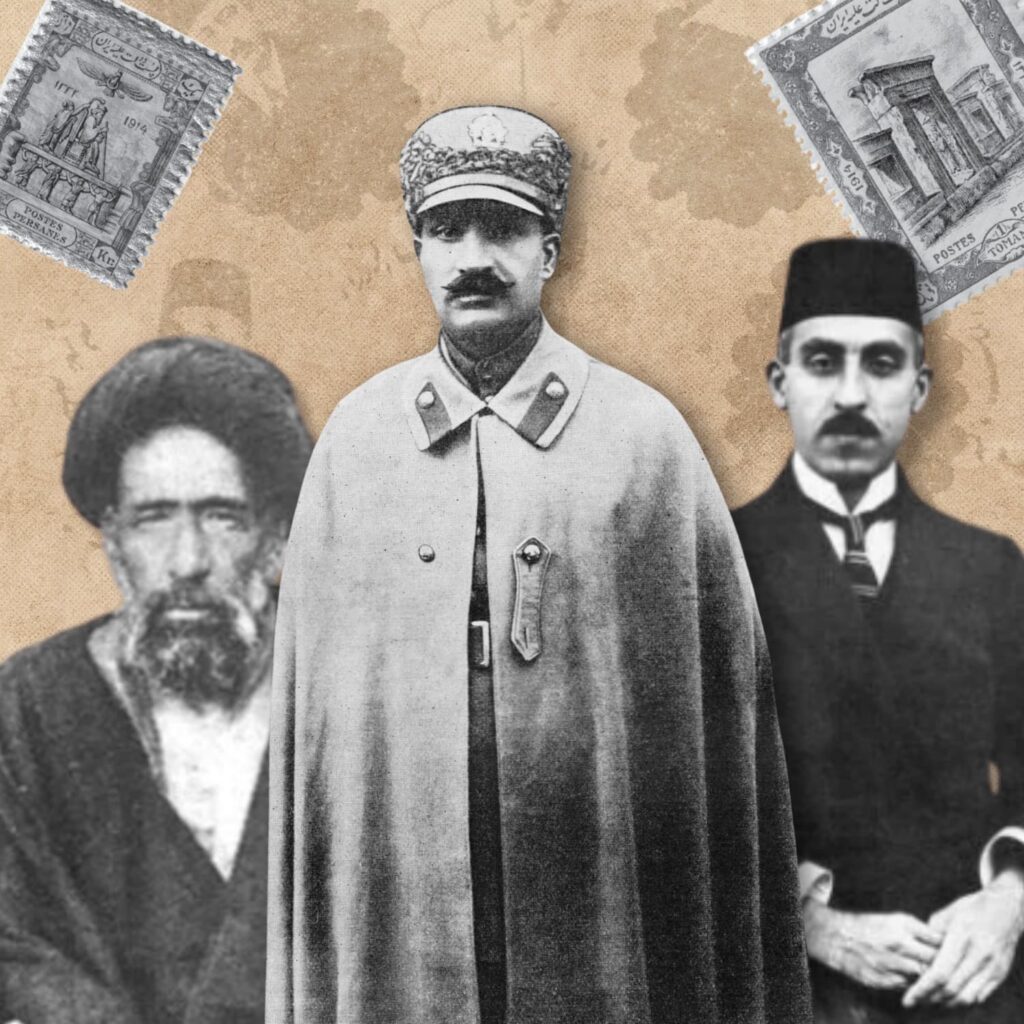

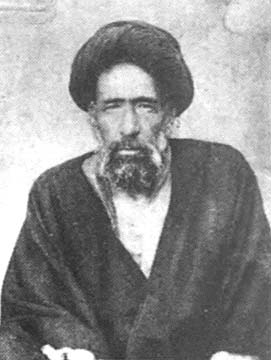

The wheat shortage of 1922, however, was the perfect opportunity for Reza Khan’s rivals to express their anger and frustration. During the shortage, people once again gathered in Baharestan Square near the Majlis building. The parliament, now in its fourth iteration, mustered a united opposition to Reza’s frivolous military spending. One of the opposing members was Hasan Modarres. Born in Isfahan, Modarres received extensive religious education in Isfahan and Najaf, becoming a respected scholar. He was later elected as a member of the Iranian Parliament. There he fiercely opposed the 1919 agreement that aimed to make Iran a British protectorate.

With Mosaddeq and Modarres angery at Reza Khan’s spending, the opposition soon spread outside of Baharestan Square. It included Journalists, liberal newspapers, and some of the Qajar nobility, including the prince regent Mohammad Hasan Mirza.

Reza Khan’s Resignation and Compromise

As mentioned earlier, Ahmad Shah had departed to Europe, using a made-up illness to get out of Reza Khan’s way. This absence meant that Mohammad Hasan Mirza, Ahmad Shah’s brother and the person next in line to the throne, was the only powerful figure standing against Reza’s actions. With parliament members uniting behind the regent, Reza knew that now wasn’t the right time to pick a fight with the establishment. In a strategic move, on October 8th, Reza resigned from his post in the cabinet. He told the parliament that he respected their views and had chosen to opt out of Iran’s politics.

Despite his forceful tactics in politics and his excessive military spending, no one could deny Reza’s impact on the country. He was a linchpin in Iran’s politics. That’s why, the very next day, Qavam al-Sal-Taneh, the prime minister, invited Reza for a sit-down with the prince regent and Modarres to find common ground between the parties and invited Reza Khan back into his cabinet. After the meeting, Reza agreed for the military budget to be regulated. The members also set a course for more freedoms for society and the press.

Departure of Shah and a New Prime Minister

The next 12 months passed without any major signs of trouble. A sign that perhaps Persia had finally deciphered the recipe for democracy. However, the following year, things escalated dramatically.

In October 1923, after a bomb went off near Ahmad Shah’s living quarters, the young king, paranoid and scared, decided to leave Iran and travel to Europe once again. Before his departure, Ahmad Shah wanted to once again name Qavam al-Sal-Taneh as the prime minister. He believed that only Qavam had the power to control Reza Khan. Ahmad Shah wasn’t a fan of the war minister in his cabinet. He even suspected that Reza was behind the bomb that had almost taken his life. He knew Reza aspired for more power and control, and by naming Qavam, he wanted to ensure that Reza was kept in check and his aspirations were regulated.

The Arrest of Qavam al-Sal-Taneh

On October 9th, Reza Khan was informed of the decision to appoint Qavam al-Sal-Taneh as prime minister. Reza knew that this was his chance at seizing power and if Qavam was selected as prime minister he might never be able to strive for anything higher than a minister of war. So he had to take things into his own hands and write his own destiny.

Shortly after, Qavam al-Sal-Taneh was arrested by the military police.

His charge? Conspiring to murder the Minister of War. His punishment? Banishment from the country.

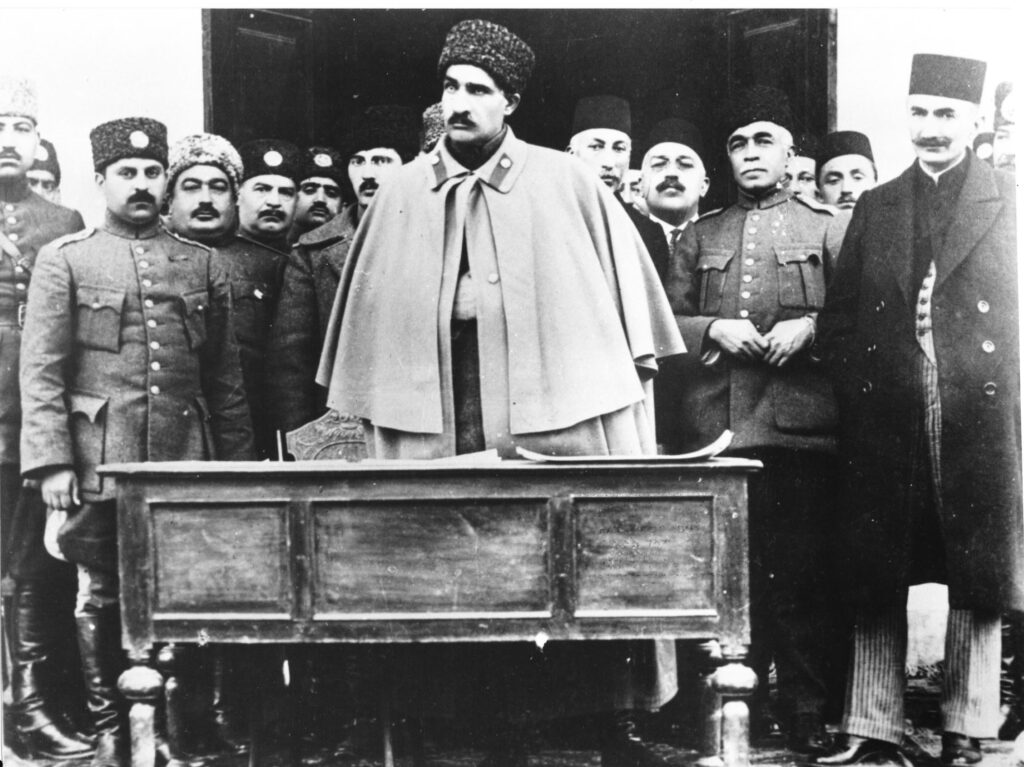

With Qavam of the picture, Ahmad Shah had no choice but to name Reza Khan as his new prime minister. Shortly after signing the decree, Ahmad Shah, weary of his own safety, departed the capital and went to Europe. The new prime minister made a point to accompany the king to the western border of the country.

There are many speculations about Ahmad Shah’s motives and decisions. The young king who grew up with the mentorship of constitutional fighters always believed in the will of the people. He never wanted to overreach his position as the king. He believed his inaction was respecting the democracy people had fought for. Some believe that this stemmed from his inability to stand up to more powerful men controlling his cabinet. But almost everyone agreed that as he left Iran, even he knew that this time, there would be no return.

Türkiye: A New Democratic Neighbour

Reza Khan, now the second most powerful man in his country, gradually strengthened his position. He simultaneously launched extensive propaganda against Ahmad Shah, portraying him as indifferent and unconcerned about the country’s fate. Reza Khan’s agents in various cities propagated the idea that the Shah had no interest in Iran and was only pursuing pleasure in Europe.

During this time, Turkey was also undergoing a major political transformation.

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920 aimed to partition the Ottoman territories among the Allied Powers. This treaty aimed to reduce the Ottoman state to a small region around Istanbul.

Enter Mustafa Kemal, a man with a vision and the courage to defy the seemingly inevitable. Known later as Atatürk, he rallied his people for one last fight, igniting the Turkish War of Independence. From 1919 to 1923, Atatürk and his nationalist forces fought against occupying Greek, Armenian, French, and British troops.

As the dust settled, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed in 1923, acknowledging the sovereignty of a new Turkish state. On October 29, 1923, a historic proclamation was made: the Republic of Turkey was born, with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk as its first president.

The Emergence of Republicanism

Witnessing this grand transformation right across the border, Reza Khan devised his own master plan. With Ahmad Shah gone and the prince regent becoming powerless, Reza also dreamed of turning his country into a republic.

Soon, he started a campaign to push for the establishment of a Persian republic in place of the Qajar dynasty.

In Persia, the end of winter marks the start of a new year. This is celebrated with the traditional Persian festival of Nowruz, or “New Day.” This celebration marks the moment when the sun crosses the celestial equator, signalling the full passage of the Earth in its orbit around the sun and the official start of spring. Nowruz is a time for new beginnings, for coming together with loved ones, and for embracing change.

Now, Reza Khan wanted to use the symbolism of Nowruz to transition Iran from monarchy to republicanism. He wanted to name himself as the first official president of the country. He was hoping that his resume, charisma, and connections that he had worked so hard on would pave the way for this transformation.

But once again, Reza had underestimated the authority of Majlis in his country.

Majlis Opposes the Movement

As mentioned, in parliament, there were factions and individuals who were against Reza Khan’s ambitions. One of these individuals was Mohammad Mosaddegh. Knowing Reza, Mosaddegh feared that with Reza’s thirst for power and control, the establishment of a republic would only translate to a military dictatorship.

But what really fueled the opposition to the idea of republicanism was the aftermath of Turkey’s republic. After coming to power, Mustafa Kemal had abolished the Islamic caliphate and was planning to transition the country into a secular nation where Islam would fade into the background.

Although Turkey was mostly Sunni, the similarities between the two countries and their two leaders were uncanny. Both Reza Khan and Mustafa Kemal Atatürk leveraged their military backgrounds and leadership skills to ascend to power, driven by a shared vision of modernization and national rejuvenation.

So it wasn’t far-fetched that Reza would want to follow in Atatürk’s footsteps. To reduce the role of Islam in Persia after becoming president.

People Reject the Republicanism

This idea angered the religious faction of the Majlis, led by Hassan Modarres. As mentioned, Modarres was another critic of Reza Khan with deep ties to the common folk. He was known as a man of the people and was known for his candid speech and down-to-earth lifestyle. But besides his popularity with the common folk, he was also a seasoned politician. He had deep ties with the religious class, Tehran’s Lutis or strongmen, and also the remaining Qajar nobility, including Prince Regent Mohammad Hasan Mirza.

Using his connections, he was able to organize a wave of protests against Reza Khan’s campaign and asked people to voice their concerns. On March 22, 1924, thousands of people came out to Baharestan Square to protest the idea of republicanism and denounce Reza Khan’s plans for the country.

It wasn’t clear if Modarres’s intentions were purely altruistic or simply a power grab at a moment when Iran’s most powerful player was at his weakest. You have to keep in mind that Modarres was also one of the people planning a move before Zia ed-Deen’s ultimate coup attempt. But either way, his actions led to a showdown between pro-monarchy forces and the military police led by Reza Khan. Reza even showed up to boost the military’s morale, but he was booed by an angry crowd and was forced to take shelter in the parliament building.

Day of the Vote: Face-Off of Ideologies

Inside Majlis, things got even more heated. The speaker confronted Reza Khan for his lack of respect for the sanctity of the building and for breaching its premises without permission. A heated debate took place between the pro-Reza Khan faction and Modarres, and the clergy even got slapped in the face by one of the pro-Republic members. Using a bit of political theatre, Modarres leveraged the personal assault and defeated Reza Khan’s bill.

Reza, angry and frustrated, left the parliament building and the capital altogether, and the pro-monarchy crowd rejoiced in the outcome. The dream of a Persian republic was dead. The Qajar monarchy had survived yet another attack on its existence.

Republicanism is Defeated: Long Live the Qajars

In the aftermath of Majlis rejecting Reza Khan’s proposal, it seemed that Modarres’s coalition had finally reined in the never-ending ambitions of Reza. But once again, he and everyone else had underestimated the resilience of Reza Khan.

After the bill was defeated, Reza Khan and his group of close advisors moved out of Tehran and into a nearby village to regroup and reassess their options. There, the prime minister came up with a plan to pick himself up once more. On March 26, four days after his humiliating defeat in parliament, Reza travelled to the holy city of Qom.

Qom, a key city in Iran, is a major center of Shia Islam, attracting millions of pilgrims and scholars. The shrine of Fatimah, the daughter of the seventh imam of the Shia religion, is a focal point for seeking blessings and offering prayers. The city is home to the largest Shia seminary and was central to Islamic scholarship.

Secretive Meetings and Change of Hearts

In Qom, Reza met with three clergies to seek their guidance. After an extended meeting behind closed doors, Reza issued a statement. He said that after consulting with the Marjas, he recognized the error of his ways. He had realized converting to a republic was not in the best interest of Iranians and the Muslim community. Reza Khan stated he no longer sought this transition and instead wanted to focus on spreading Islam and fostering the nationalistic identity of the country.

Modares knew that this sudden change of opinion was Reza’s act. He knew that he would not stop his pursuit of total power anytime soon. Thus in July 1924, he held a vote of no confidence in Reza Khan, aiming to oust him from government once and for all. His reasoning was that Reza wasn’t upholding the decorum of the prime minister’s position. That his actions were unconstitutional and illegal. However, Reza had successfully restored his image over the past few months, and Modares’ campaign failed by a vast margin.

This defeat was due to multiple factors. First, Reza Khan had backtracked on his anti-Islam stance, weakening the unity of the religious faction. Second, even at his lowest, Reza still had significant support within the public and Majlis. Third, through fear tactics, intimidation, and physical attacks, Reza solidified his position as a ruthless player, making neutral figures prefer not to oppose him.

In his statement, Reza mentioned that he wanted to focus on spreading Islam and the nationalistic identity of Persia. In the following months, he delivered on that promise. He began to show respect for Islamic traditions and sought the counsel of religious figures on important topics.

Reza Khan’s Resurgence

Throughout the next year, Reza Khan’s efforts to modernize Iran and reduce foreign influence gained popular support. His initiatives included reorganizing the military and implementing infrastructure projects, which increased his influence. He borrowed symbolism from ancient Persia, comparing himself to Nader Shah, a king who saved Iran from foreign intruders, and Cyrus the Great, the founding father of the Achaemenid Persian Empire.

All this made the Qajar dynasty appear more foreign by the day. With their Turkic-Mongolian heritage, they were never truly Persian, and with Reza Khan comparing himself to the old kings of Persia, their legitimacy faded. Witnessing this from afar, Ahmad Shah was hesitant to return home. He felt that even if he returned, there was no guarantee that Reza would let him live, thus preferring his voluntary exile.

For the past 131 years, the Qajar dynasty ruled Persia without challenge. They maintained power through national famine, uprisings, global wars, and foreign invasions. They shrank Iran’s vast empire, sold off its resources, and kept the country stagnant while the rest of the world progressed. But this time, things were different.

With an ambitious figure seeking full control, an indifferent Shah exiled by choice, and a country weary of continuous weakness and defeat, the end was very near.

The End of the Qajar Dynasty

In February 1925, Reza Khan informed his close allies that he was no longer willing to work with the monarchy. He wanted them gone.

His counsel reminded him that according to the Persian constitution, drafted shortly before the death of Mozaffar al-Din Shah, denouncing the reigning monarchy would be illegal and lead to his removal from office. Understanding the need for a calculated approach, Reza decided to rephrase his request. If he couldn’t directly call for Ahmad Shah’s dethronement, he could use the Shah’s absence as an excuse to request full authority from the parliament.

At this time, the fourth Majlis had concluded and the fifth session had just been inaugurated. This assembly was highly supportive of Reza Khan and granted him the title of Supreme Commander of the country.

This title effectively made Reza Shah the king’s regent. The Qajar dynasty, with its king absent, was reduced to a formal monarchy, its influence in Persian politics all but erased.

A Brave New World

As you’ve learned throughout this episode, Reza Khan was not one to settle. He had once dreamed of establishing a republic, moving away from monarchy, but had to abandon the dream after a significant loss to the religious populous.

Perhaps if Iran had adopted republicanism, its history would be different today. Even if Reza had transformed his republic into a military dictatorship, it might have sparked the change necessary to secure Iran’s democracy in the long run. But history had other plans, and the dream of a republic was officially pronounced dead.

Despite the death of the Republic of Iran, Reza Khan remained determined to remove the Qajar stain from Iran’s canvas. If the nation wouldn’t accept him as president, he would declare himself the new king. He’d establish a new dynasty in his name and usher in a new era for the country he had worked so hard for.

A dynasty in his name, made by him, devoted to his kin and dedicated to the betterment of the land of the lion and the sun.