This is the transcript for Book Two, episode 3 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: God, Shah, Nation. This story is about the events after the abolishment of the Qajar dynasty and Reza Shah’s coronation as the new king of Iran. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

New Beginnings: Nowruz in Iran

For Iranians, March has always been a month of change. It marks the moment when the Sun crosses the celestial equator from south to north. This signals the first day of spring in the Northern Hemisphere. It’s the beginning of the astrological year in the Persian calendar. This event, known as Nowruz, holds deep cultural and historical significance for Iranians.

In 1935, Nowruz carried an even greater symbolic weight. A decade had passed since the establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty, and with it, a series of sweeping changes had transformed the country. That year, the government decided to mark the new year with a special announcement.

The announcement came in the form of a memo to all foreign legations. It was short, direct, and momentous: a request to officially change the country’s name.

Persia vs. Iran: Which Name to Use?

Before Reza Shah’s reign, the country did not have a universally recognized official name throughout the world.

For much of its history, the outside world primarily knew the country as “Persia.” This name had been used by Western nations, largely due to the influence of ancient Greek and Roman writings. They still had memories of the vast empire ruled by the Achaemenid dynasty.

The name “Persia” became deeply ingrained in Western consciousness, often symbolizing the nation’s cultural and historical heritage.

But there was a problem with the name.

As we’ve discussed throughout this podcast, Persia was a land of diverse nationalities, ethnicities, and tribal groups. The country includes Persians, Azeris, Kurds, Lurs, and many others. The name “Persia” excluded the vast range of identities within the country’s borders, failing to reflect its multi-ethnic composition.

Reza Shah’s Decision: Persia is now known as Iran

Reza Shah wanted a name that represented this broader coalition of peoples. He wanted to symbolize a fresh start for the nation under his rule.

Learn more about the name “Persia”

As the new year celebration of 1935 arrived, the government decided to celebrate the festivities with a big change. The announcement came in the form of a memo to all foreign legations. It was short, direct, and momentous:

“Effective immediately, the use of the name Persia is discontinued. From now on, the country shall be recognized as Iran.”

Signed,

The Government of His Imperial Majesty, Reza Shah Pahlavi”

Understanding the Tools of Authoritarian Governance

Not all kings succeed in maintaining their rule. When it comes to monarchies, especially the authoritarian ones, their effectiveness hinges on access to and mastery of the tools of authoritarian governance. Tools such as centralized control over resources, surveillance systems, and the force to implement and protect their will.

The Qajar kings were the perfect example of the failure of this system.

All Qajar kings after Agha Mohammad Khan failed to wield power, resulting in weak and unstable reigns. Although they operated as authoritarian monarchs, they lacked the tools and systems necessary to maintain centralized control. Their inability to assert dominance over regional elites, implement effective taxation systems, and modernize the military left them vulnerable to internal and external pressures. Their power shrank king after king. By the end of their reign, they barely had any control over Iran’s vast resources.

Rulers consolidated power by building strong institutions, yet the Qajars neither invested in nor controlled such institutions.

Reza Shah aimed to be the exact opposite.

“God, Shah, Nation”: Reza Shah’s Guiding Motto

The motto “God, Shah, Nation” was adopted by him to represent the interconnected pillars of his rule and the new Iranian state he was building.

A slogan reflected a key aspect of Reza Shah’s ideology, which combined religious, monarchical, and nationalistic elements.

Before he could fully exert his powers as king, he needed to rebuild the tools that Qajars had failed to create. The most important of which was the existence of a strong military and centralized control over Iran’s resources.

As a colonel in the Cossack Brigade and later a minister of war, Reza Shah had begun the process of solidifying Iran’s army long before his ascension to the throne. Yet, even after unification, Iran’s army didn’t have much to offer. In 1921, the military totalled no more than 22,000 men. 8,000 Cossacks, 8,000 Gendarmes and 6,000 South Persian Riflemen. Reza Shah wanted to double that number.

Compulsory Military Service in Iran

To achieve this goal, Reza Khan and the fifth parliament passed the Compulsory Military Service Conscription Law in June 1925.

This law mandated that all Iranian males, both residing in the country and abroad, were required to serve two years in the military upon reaching the age of 21.

Initially, conscripts were mainly drawn from the peasantry and tribes, but later, the selection expanded to the urban population. The men selected for military service were forced to leave their tribal life. They had to spend time learning military and organizational skills. Most importantly, they had to learn Persian, the official language of the country. This further advanced the national unity aspirations of the King.

Resistance to Military Conscription: Landowners and Clergy

When introduced, the law faced opposition from large landowners and the clergy.

Landowners resisted because conscription threatened their authority and reduced the workforce on their estates. The clergy opposed it on the grounds that two years of service in a secular military, administered by anti-clerical officers, would erode the religious beliefs of recruits. Some mid-ranking clerics even issued fatwas declaring the law a danger to Shia and Islamic principles.

Reza Khan, with the support of the officer class, overcame resistance from the landowners. Clerical opposition was mitigated by securing the prior approval of senior Shia figures. Theology students were also granted exemptions.

By the end of 1925, Iran’s army had reached 40,000 troops. By 1941, the army had more than 127,000 at its disposal.

With a strong military in place, the second issue was the centralized control over Iran’s resources.

Reza Shah’s Challenge: Ruling Over a Decentralized Nation

In book one, we talked about the many tribes that roamed Iran’s vast landscape. By the early 1920s, over 60% of Iran was controlled by different tribal groups. These tribes had immense power over their regions, and some even refused to answer to the central government. A great example is Sheikh Khaz’al of Khuzestan, a story which we covered in the previous season.

Throughout the early 1920s, Reza Khan started to face these tribes and bring them under control. Some, like the Bakhtiarys, through diplomacy and others, like Sheikh Khaz’al and Mirza Kuchak Khan, through brutal force.

Reza Khan’s strategy had always been to sow conflict between the tribes. He’d then use their inner conflicts to quash their influence. By 1927, Reza Shah had largely succeeded in breaking the power of the major tribal families that had wielded their significant century-old influence.

But defeating the tribes wasn’t enough to unify the country.

Iran, for most of its parts, was a disconnected landmass.

Iran: A Disconnected Landmass

The many desserts, mountains and rivers made mobility all but impossible in this region … That in itself was one of the main reasons why so many tribes were able to take control of every region of the land.

Getting from one province to another meant days, sometimes weeks, of travel through unstable roads, rough terrains and dangerous environments. That’s why a functional infrastructure was required to connect the country together.

For Reza Shah, this interconnectedness came in the form of the Trans-Iranian Railway.

The idea of a railway connecting the vast Iranian landscape had always been a dream too good to come true.

The National Railway System in Iran: A Historical Struggle

In 1872, Baron Paul Julius Reuter secured a concession from Naser al-Din Shah. The concession granted him extensive rights to construct railways and exploit resources. However, domestic opposition and international pressures led to the cancellation of this concession. A story which we’ve covered in the very first episode of our podcast.

Subsequent attempts to establish railways faced similar challenges.

In 1889, Russia and Iran agreed that no railways would be built in Iran without Russian consent. The agreement aimed to protect Russian commercial interests against Britain’s ever-growing presence in the south … An agreement that was later nullified during the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1910.

Despite this nullification and due to a lack of funds and constant disagreements between Britain and Russia, the railway project remained stalled for decades to come.

The Trans-Iranian Railway

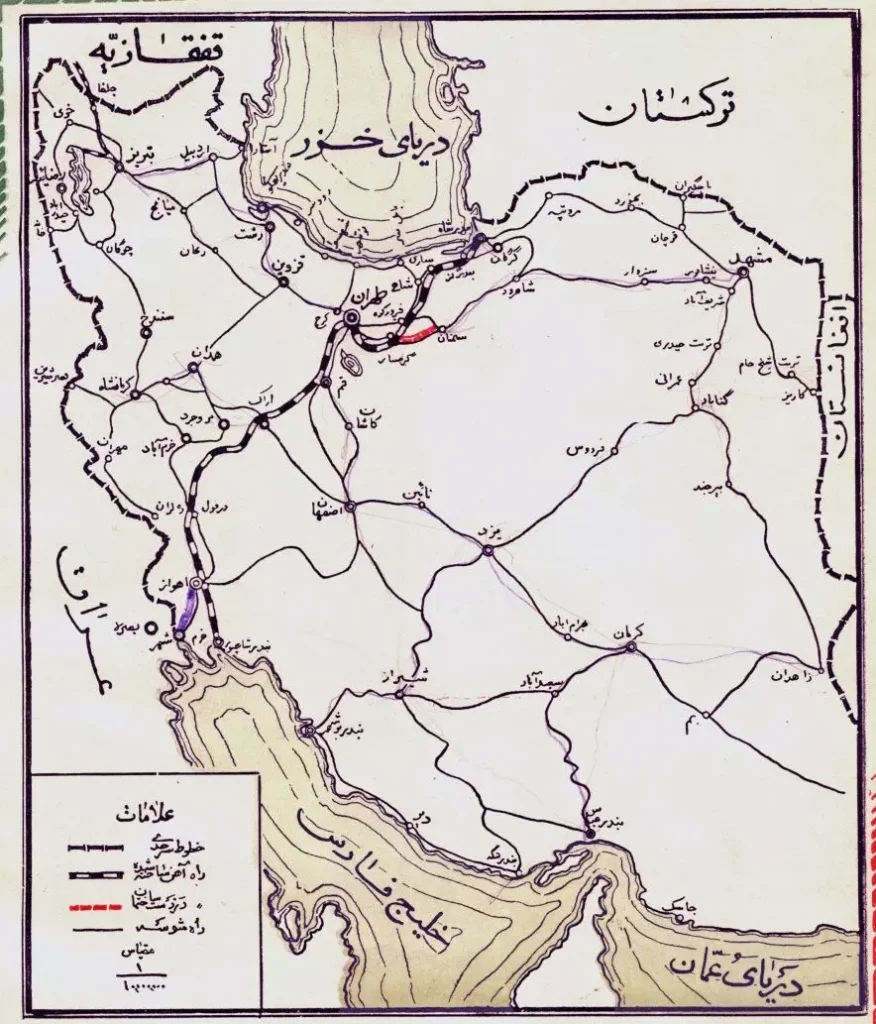

After the coronation, the new king wanted to rekindle this dream. He wanted to embark on making the single biggest infrastructure project in his country a reality. To connect the Caspian Sea in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south and, in the process, bring the two ports to the capital.

In the north, the railway would start from Bandar e Shah, the king’s port in the Mazandaran and end in the port of Khoramshahr in Khuzestan.

Mazandaran was Reza Shah’s home state, and thus, he had a high interest in its development. Khoramshahr was also an important port in the critical state of Khuzestan. Having a direct route to this southwest state allowed the government to expand its control over it, have a bigger stake in its refined oil and use it as an import-export hub to the Western world.

Funding the Trans-Iranian Railway: Leveraging National Resources

The Trans-Iranian Railway project was a massive and expensive undertaking for Iran. A country that was still suffering from the aftermath of the First World War. What made this project even more remarkable was Reza Shah’s determination to complete it without relying on ANY foreign loans or aid.

The reckless borrowing of the Qajar kings had left a bitter legacy in the minds of Iranians, and Reza Shah was intent on ensuring his new dynasty would not carry the same stain. He wanted the railway to stand as a wholly national achievement, funded entirely by Iran’s own resources.

But where would the government find the funds for this extremely ambitious and expensive project?

As you may know, tea has long been a staple of Iranian life. The national demand for tea far outstripped domestic production, making imports essential. In May 1925, the parliament approved a government monopoly on the import and export of tea and sugar. This granted the Pahlavi dynasty full control over the management, pricing, and sales of these essential commodities.

Leveraging this control, the government introduced a value-added tax on tea and sugar imports, funnelling the proceeds directly into funding the railway.

The Scope and Impact of the Trans-Iranian Railway

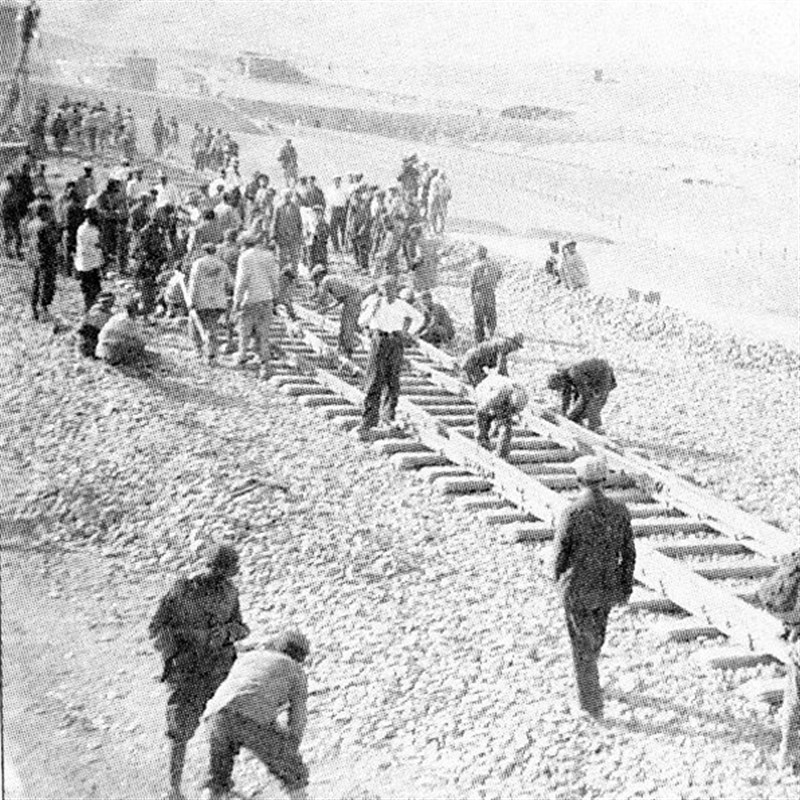

The project officially began in 1927.

Spanning a massive 1,394 kilometres, the railway navigated Iran’s challenging terrain through a network of tunnels and bridges, with its highest point reaching 2,200 meters above sea level. While several foreign firms were involved in its construction, the Danish company Kampsax ultimately completed the project under budget and ahead of schedule.

The railway was formally inaugurated on August 26, 1938.

Costing 10 billion rials (equivalent to 500 million dollars at the time), the Trans-Iranian Railway became the most expensive and extensive independent project in Iran’s modern history.

It was a testament to Reza Shah’s ambition and strength, symbolizing a clear break from the Qajar era and cementing the distinction between the two dynasties.

But the Trans-Iranian Railway wasn’t the only new infrastructure project of that era.

Connecting Iran: Expanding Roads and Infrastructure

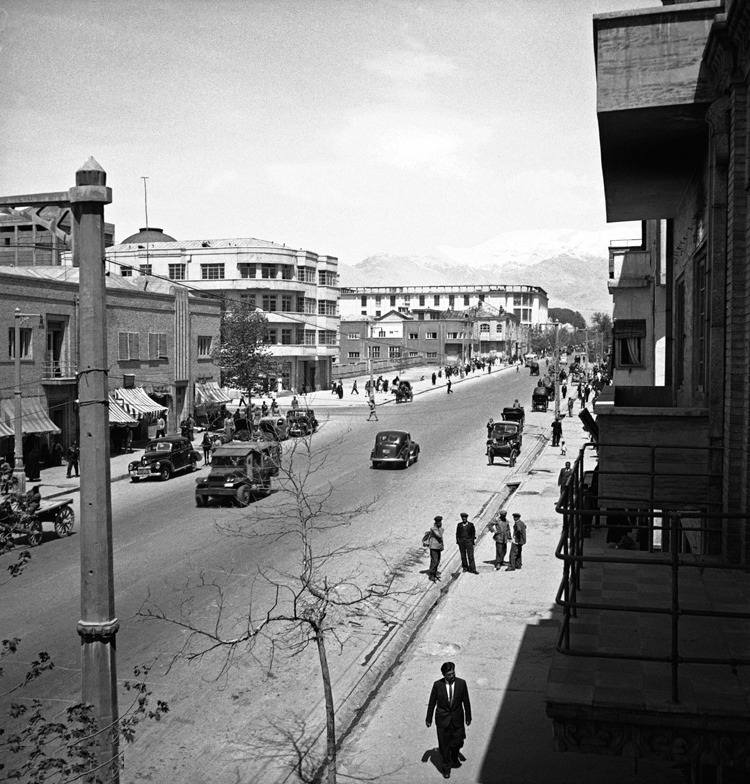

Before the coup of 1921, Iran had a mere 2,400 kilometers of roads. By the end of the 1930s, this network had expanded to over 22,000 kilometers. For the first time, most Iranian cities were connected by a modern transportation infrastructure.

This transformation ushered in a new era of motor vehicle culture. Cars, trucks, and buses quickly became commonplace, replacing the reliance on camels as the primary means of transport. Journeys that once took 20 days could now be completed in just over a day.

This newfound mobility revolutionized the exchange of resources, labour, and news, accelerating the pace of development and integrating different parts of the country like never before.

Reza Shah now had access to a unified military, and with the establishment of trains, roads, and improved safety, he could exert control over the vast Iranian landscape.

Yet controlling a country as large and diverse as Iran required more than infrastructure and a strong military presence. One man couldn’t oversee everything or handle every issue.

To truly govern effectively, a structured system was essential—a bureaucracy had to be established.

The Bureaucratic Revolution: Expanding Governance Under Reza Shah

The Pahlavi dynasty inherited four ministries from the 19th century: Foreign Affairs, Finance, Justice, and Interior. By the end of Reza Shah’s reign, there were eleven fully fledged ones.

Among them, the Ministry of Interior took charge of provincial administration.

Under Reza Shah’s rule, Iran’s eight provinces were expanded into fifteen, and each province was further divided into counties, municipalities, and rural districts. The interior minister appointed governors-general, who then selected regional officials and town mayors. Gone were the semi-autonomous tribal leaders who once governed these regions with little oversight. Instead, governors and officials were now public servants, all of whom had sworn loyalty to the crown.

For the first time, Reza Shah could control every corner of his country and with this control came ownership.

Consolidating Power: Reza Shah’s Expanding Control Over Iran

By the time of his death, Reza Shah owned over 3 million acres of farmland and had amassed a fortune of 3 million pounds—equivalent to 113 million pounds in today’s value.

According to the British legation, Reza Shah had an “unholy interest in land,” often acquiring properties through questionable means. This included imprisoning landowners until they agreed to sell at heavily discounted prices. His ambitions were particularly evident in Mazandaran, his home province. Reza Shah ensured the Trans-Iranian Railway ran directly through Mazandaran and invested heavily in the region, building luxury hotels, state factories, and road networks.

The king’s ability to pursue his personal goals and nationwide ambitions came from his relentless expansion of state power into every aspect of Iranian politics. The parliament, which had been instrumental in his political rise, became little more than a rubber stamp for his agenda.

Manipulating Elections and Eliminating Dissent

To ensure complete control, Reza Shah meticulously manipulated the elections, turning the Majlis into an assembly of loyalists.

The process was straightforward: through the Ministry of Interior, Reza Shah was provided with a list of prospective candidates for each election. With the help of his chief of police, he would classify them with labels such as “suitable,” “bad,” “unpatriotic,” or even “stupid.”

The local electoral boards would receive the adjusted list, and only those marked as “suitable” were allowed to run, ensuring the electoral boards complied with his directives.

However, controlling the election process wasn’t enough for the king. He wanted absolute compliance within the Majlis.

To achieve this, he removed parliamentary immunity, banned political parties, and shut down independent newspapers. He also planted informants within the chamber to monitor and report on any potential dissent.

Even Hassan Modarres, the once-powerful critic turned ally who, only years earlier,r granted Reza Shah unlimited authority, was not spared. Modarres was banished from the Majlis and exiled to Khorasan, where he met an unexpected and suspicious death.

These actions fostered an atmosphere of uncertainty and fear. As the British Minister to Iran observed:

“The Cabinet was afraid of the Majlis, the Majlis was afraid of the army, and all were afraid of the Shah.”

This state of total control allowed Reza Shah to exert his might in other areas as well, including direct intervention in the market. An intervention that created the first real conflict of his reign.

A New Financial Advisor Appears: Arthur Millspaugh

In 1922, just as Reza Shah was becoming the prime minister of the country, the parliament had passed a law allowing the hiring of Dr. Arthur Millspaugh.

Millspaugh was a former advisor to the US State Department’s Office of Foreign Trade who had been hired with the purpose of updating Iran’s finances and generating greater state revenue, especially through taxation.

Hiring foreign experts to mend Iran’s finances wasn’t a new thing. You may remember the story of William Morgan Shuster, who came to Iran in 1906 after the constitutional revolution. He aimed to help Iran with its finances but was ultimately forced out by the Russians, and his mission was left unfinished.

Now, Millspaugh had come to finish that mission!

On the 23rd of July 1922, a law was passed by the Iranian parliament in the cabinet of Qavam al-Saltaneh. According to this law, Millspaugh was hired with an annual salary of $15,000, along with housing and furnishings provided by the government for him and his eight other American colleagues.

By late 1922, the foreign advisors arrived in Tehran and began their work.

The Economic Reforms of Dr. Arthur Millspaugh in Iran

The law granting Millspaugh employment gave him full authority, ensuring that no expenses were made without his approval and no financial commitments could be made by the government without his consent.

The finance minister at the time had no authority in relation to Millspaugh, and the entire structure of the Ministry of Finance and the provincial administrations were under the direct supervision of Millspaugh and his American colleagues.

Millspaugh tried to implement the American model of internal revenue collection while the British war subsidy was being phased out. He worked to rationalize fiscal policies, produce detailed annual budgets, and reduce inefficiency. He also cancelled tax exemptions that had been previously granted by Qajar Shahs and tried to create a semi-equal sovereign state where everyone would pay their own fair share and contribute to the country’s internal income.

Millspaugh’s reforms had successfully increased government revenue. As Reza Shah replaced the Qajar monarchy, this helped strengthen the Pahlavi state. Millspaugh’s efforts helped people see Reza Shah as an economic saviour … but Reza Shah’s vision for the economy was fundamentally different.

Reza Shah’s Economic Vision vs. Millspaugh’s Fiscal Philosophy

The king wanted the government to dominate Iran’s industry and market. State monopolies were to oversee the country’s key resources, controlling supply and demand. It began with the Sugar and Tea monopoly in 1925 and later extended to the Opium and Tobacco industries, with profound social significance. You may remember that government interference in the tobacco trade decades earlier had led to one of Iran’s most pivotal societal shifts.

These policies stood in direct opposition to Millspaugh’s economic philosophy. But there was more. As he had done during his tenure as prime minister, Reza Shah devoted large portions of the budget to military expansion. With mandatory military service now in place, he demanded that all of Iran’s oil revenue be allocated to the military.

Millspaugh viewed this as a looming financial disaster.

Yet, Reza Shah didn’t really care about what others thought.

Under mounting pressure from the government and the king himself, Millspaugh had no choice but to resign and leave his post … the second financial advisor to fail in his mission and be forced out of the country.

Étatisme: Reza Shah’s Economic System and State-Controlled Industry

With Millspaugh gone, Reza Shah turned to étatisme in the industrial sector.

Étatisme refers to the belief or policy that the state should have a central role in economic and social matters. It advocates for government intervention or control over various sectors, such as industry, education, and welfare, to ensure stability, economic growth, and the well-being of citizens.

In a nutshell, Reza Shah wanted to control every aspect of Iran’s economy.

Before Reza Shah’s reign, Iran had fewer than 50 factories. By the end of his nearly 17-year rule, that number had risen to 300. The government became the primary investor in many of these factories, offering low-interest loans to encourage investment and drive industrial growth.

Establishing a New Banking System in Iran

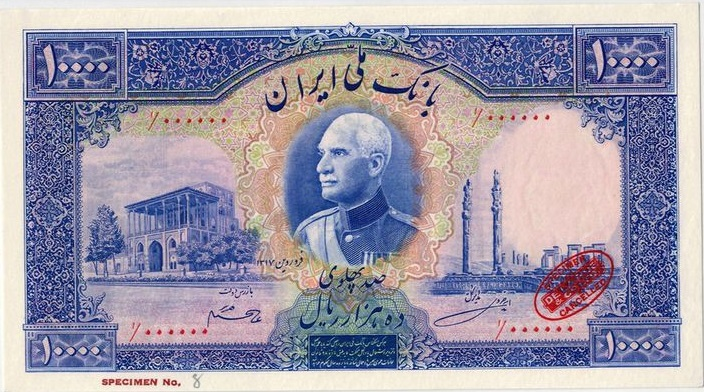

The financial sector was another area where the government played a pivotal role. In 1927, the Bank Mel’li, or National Bank, was established, functioning as both a commercial bank and the government’s central bank. This was a significant step in asserting national sovereignty. The Bank Melli took over the right to issue banknotes from the British-owned Imperial Bank of Persia and assumed responsibility for currency and foreign exchange control, along with other central banking functions.

For the first time since the late 1800s, new banknotes were designed, replacing the face of Nasir al-Din Shah with the image of the new king. In 1932, the country’s official currency was changed from the Qiran to the Rial—a currency that remains in use to this day.

By the end of Reza Shah’s reign, at least four major Iranian banks were in operation: the National Bank, the Pahlavi Bank for Army Veterans (Bank Sepah), the Mortgage Bank, and the Agricultural Bank.

Reza Shah’s Ruthless Reforms: Legacy and Transformation

It is often said of Stalin that he “inherited Russia with horse and plow and left it with an atomic bomb,” … a quote mistakenly attributed to Winston Churchill. Regardless of its origin, a similar sentiment could be applied to Reza Shah.

When Reza Shah came to power, he inherited a nation crippled by a paralyzed government, riddled with ineptitude and incompetence. What he left behind was a centralized system with infrastructure that endures to this day.

He unified Iran’s fragmented army, connected the country’s vast and diverse landscape with roads and railways, and, for the first time in its history, established a functional bureaucracy.

Reza Shah was indifferent to the opposition, unbothered by left or right politics, and undeterred by what others deemed impossible. He wasn’t a politician. Reza Shah had no ideology or adherence to a specific political theory.

He was a king with a vision for his kingdom.

For Reza Shah, the monarchy was an extension of himself, inseparable from the state.

In his view, the monarchy controlled the nation, and the nation was one and the same as the monarchy. Nothing was going to stand in the way of turning his vision into reality. Not individuals. Not Institutions and not even the people.

The Rise of Reza Shah’s Authoritarian Rule

His motto was three words: God. Shah. Nation.

To Reza Shah, this trinity represented the ultimate path to Iran’s success.

Any opposition to any part of this triad was seen as subversion and treason. In other words, opposition to the Shah and his vision was the same as betraying the country and even defying the words of God.

But the troubling thing began in the second half of his reign as king. As time went on and Reza Shah’s power grew, the middle word—Shah—began to overshadow the rest, becoming the dominant force in his rule. It was no longer God, Shah, Nation so much as it was Shah, Shah … and Shah!

In the next episode of The Lion and the Sun, we’ll see how the Shah exerted his power over Iran’s oil resources, defying the wishes of his former foreign allies to assert his country’s independence—even at the cost of its benefits.

2 Responses