This is the transcript for Book Two, episode 4 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: APOC. This story is about the clash of Reza Shah’s government with the British over Iran’s oil contract and the rise and fall of Teymourtash. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

The room was quiet. The only sound came from the crackling wood in the fireplace.

Outside was harsh and cold, but the fire kept the chamber warm.

The hour was late, perhaps even past midnight.

Inside the palace, the Shah was in the main government building, surrounded by his ministers.

They sat in silence, waiting. For something. Or someone.

The meeting should have ended hours ago, but the king was not satisfied. Something was missing.

The silence stretched for what felt like an eternity … until finally … the heavy wooden doors creaked open. A man entered. He had a well-groomed mustache, a strong jawline, and a broad forehead, giving him a commanding presence. But his commanding presence folded as he got closer to the king.

He was carrying a thick file in his hands.

Reza Shah’s Inner Circle and the Oil Crisis

Teymourtash was never late. But lately, something had changed within him. The man whose word had once been the word of the king now seemed distracted. Uneasy.

He walked directly to the Shah and handed him the dossier.

The king didn’t acknowledge him. He snatched the file from his hands and flipped through it, barely looking at the pages.

“Is that it?” he asked, his tone indifferent.

Teimurtash nodded.

For a moment, the king contemplated his actions … then, without a second glance, he tossed the file into the fire. The ministers watched in stunned silence as the flames consumed the pages.

The file contained the agreement signed by Mozaffar al-Din Shah a quarter of a century earlier—the contract between the British Empire and the Kingdom of Persia, the deal that had bound Iran’s most valuable resource to foreign hands.

“No one leaves this room until the oil agreement has been sorted,” the Shah commanded as he left the room.

The room was quiet. The only sound came from the crackling wood in the fireplace and the whisper of paper turning to ash.

Reza Shah had just erased the biggest economic contract in his country’s history.

A Century of Iran’s Oil Struggles

The modern history of Iran has always been intertwined with the story of oil. The valuable resource that the country had unlimited barrels of it.

Last season, we talked about William Knox D’arcy, a British businessman, who in 1901 secured the exclusive rights to search for oil in southern Persia. Initially, D’Arcy’s team, led by George Reynolds, faced harsh conditions and failed to find oil for several years.

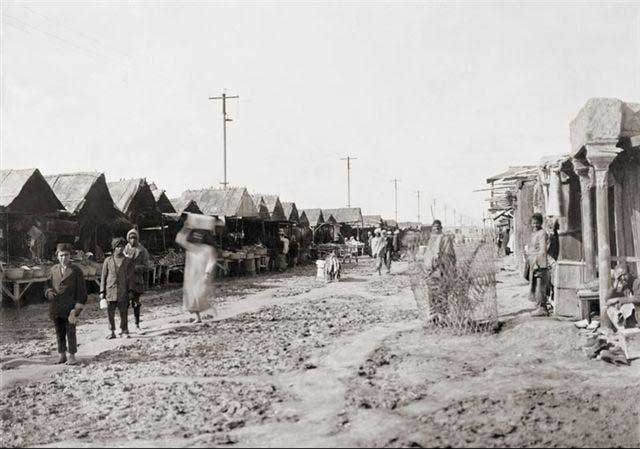

But in 1908, just as they were about to give up, Reynolds struck oil in Masjid-Soleiman, marking a groundbreaking discovery. One of the largest reserves in the world.

This find led to the formation of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), which took over the rights and exploration of Persia’s vast oil reserves. The British recognized the value of these reserves, and in 1914, Winston Churchill’s government bought a controlling stake in APOC, ensuring access to oil to fuel Britain’s navy.

(Read the full story here)

While APOC was now in charge of oil extraction in Iran, it was still functioning under the original agreement between Mozaffar Al-Din Shah and William D’arcy. This meant that the company had to comply with its financial obligations.

How the Anglo-Persian Oil Company Exploited Iran

When the agreement was signed, D’Arcy provided the Shah with an advance of £20,000, an equal amount in company stocks, and a promise of 16% of the net profits from oil extraction.

The British didn’t like that. They saw themselves as the ones doing the real work => their investment had funded the exploration, their infrastructure had transformed Abadan, and their market development had made the oil industry viable. To them, sharing such a large portion of the profits with a country that had no part in the process seemed excessive. So they began bending the rules .

APOC was required to pay Iran 16% of its net profit. The lower the net profit, the smaller Iran’s share would be.

The company exploited this loophole through its network of subsidiaries, including the Bakhtiari Oil Company. APOC would sell the extracted oil to its own subsidiary at artificially low prices, only to repurchase it later at market rates. On paper, this created enormous losses, reducing the company’s net profit while keeping the real money circulating within its own corporate ecosystem. The only loser would be Iran’s government.

Iran Uncovers APOC’s Accounting Tricks

The Iranians had no idea. They couldn’t even decipher APOC’s financial records, as they were written in English. To make sense of the books, they had to hire an outsider—an accountant who could translate and analyze the numbers. Only then did they uncover the truth: the British had been deceiving them for years.

It wasn’t just the shady accounting practices. APOC had also been inflating its operational expenses, ensuring that Iran’s final share shrank year after year, even as oil profits reached record highs.

Outraged, Iran demanded a renegotiation of the deal—insisting on a fairer share of the wealth generated by a resource that, by all rights, belonged to them.

The British welcomed the request with open arms.

Despite all the accounting tricks, inflated costs, and record-breaking revenues, the British weren’t happy with the agreement either.

The D’Arcy Agreement: A Flawed Deal

The original D’Arcy agreement wasn’t tax-exempt. Since the Anglo-Persian Oil Company operated within Iran, no amount of creative accounting could fully exempt it from paying taxes to the government. The British wanted to change that.

From the British perspective, the agreement had another flaw: It wasn’t crafted by a professional business negotiator, and its structure reflected that. The deal followed a classic revenue-sharing model, where Iran received a percentage of total profits. But the British government and APOC shareholders preferred a revenue-per-barrel model, which was more common in their other oil dealings. In this structure, the partner country would receive a fixed payment per barrel extracted, rather than a share of overall profits—giving the British tighter control over costs and payments.

And finally, there was the issue of time. The D’Arcy agreement was set to expire in 1961. The British wanted to extend it until the end of the 20th century, securing their foothold in Iran’s oil industry for decades to come.

But as both sides signaled their willingness to revisit the past, another event was reshaping Iran’s political landscape.

1921 Coup: The Rise of Reza Shah and Iran’s Oil Politics

You probably remember the coup of 1921—the second biggest coup in Iran’s history. (The first? We haven’t gotten to that yet!) The coup of 1921 was about the journalist who became prime minister and a colonel who became his Minister of War.

The British were supportive of the coup—some say they even orchestrated it. But beyond its immediate political impact, the coup had another consequence: it introduced Reza Khan to the foreign powers operating within Iran. And with that, a chain reaction began.

(Read the full story here)

As Minister of War, Reza Khan set out to unify Iran’s fragmented military. Later, as the prime minister, he began to crush the rogue tribal forces that controlled the country’s borders. Among them was the Banu Ka’ab tribe in Khuzestan, led by Sheikh Khaz’al. A story we’ve covered in our two-part Arabistan episode.

How Britain Backed a Rogue Oil State in Khuzestan

Khaz’al was a tribal leader in Khuzestan, backed by the British to safeguard their oil interests in the southwest. In return, they provided him with money, weapons, and even a knighthood!

But there was a problem. Over time, Khaz’al’s power in the region made him indifferent to the central government. He refused to pay taxes. He ruled as if Khuzestan was his own kingdom.

For Reza Khan … this was unacceptable.

As he prepared his army to march south in 1924, he made his case to the British: they no longer needed Khaz’al. If their main concern was the security of the oil refineries, Reza Khan would personally guarantee their safety and protect British assets in the region.

The British, seeing a new strong ally in Reza Khan, accepted the proposal. They withdrew their support for Khaz’al, clearing the way for Reza Khan to quash his rule once and for all. After his victory, Reza Khan even visited the oil lands and saw firsthand the empire that the British had made for themselves.

(Read the full story here)

This visit triggered a question in him.

Why were the British controlling the oil that rightfully belonged to his country?

Pahlavi Dynasty and Iran’s Struggle for Oil Independence

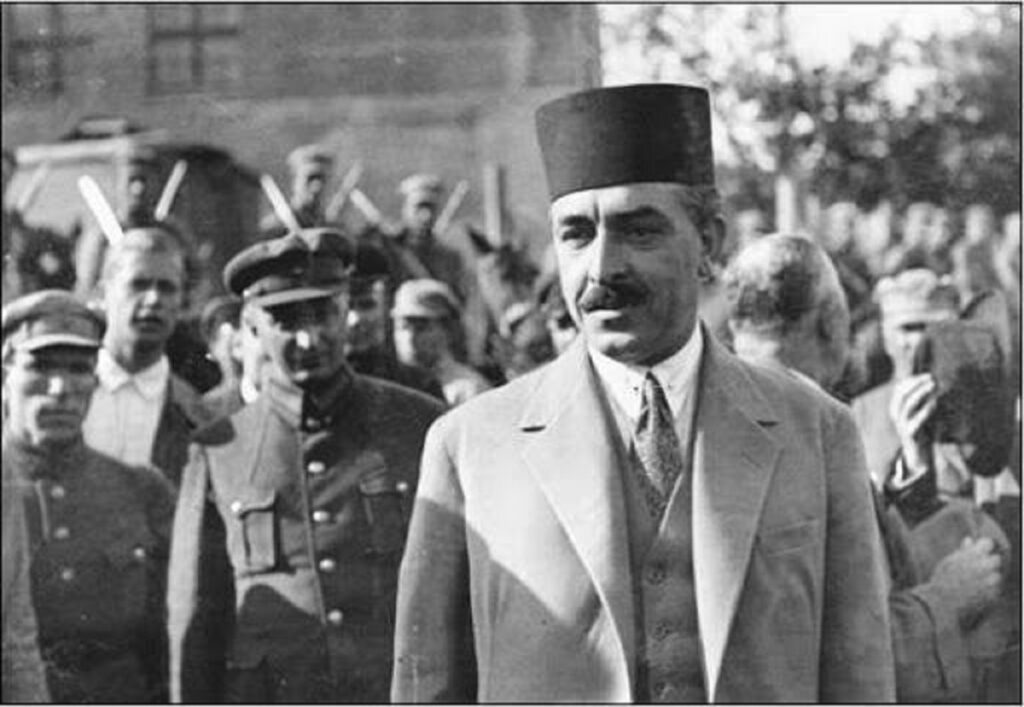

The following year, the Majlis voted to abolish the Qajar dynasty, and soon after, Reza Khan ascended the throne.

Iran had a new monarchy, but one thing remained unchanged. The D’Arcy agreement was up for renegotiation.

Reza Shah had grand ambitions for his country. He wanted to expand the military, build a railway, and establish factories to industrialize the economy. But all of these plans required capital, and Iran’s most valuable source of revenue was its oil industry. If he wanted to fund his vision, he had to renegotiate the agreement and secure a greater share of the profits.

As we’ve previously discussed, Reza Shah hated all things Qajar. And since the oil agreement was a relic of the Mozaffar al-din shah era, he couldn’t help but resent it.

The government’s stance became clear: the D’Arcy agreement was a colonial imposition, a deal that had exploited the weakness of the Qajars and been forced upon the Iranian people. By this time, Reza Shah had complete control over the press, and his propaganda machine worked tirelessly to reinforce this narrative.

“Reza Shah knew how to get things done.”

“He was going to negotiate a better deal.”

“Saving his country yet again!”

For this important task, Shah assigned his most politically savvy player: Teymourtash

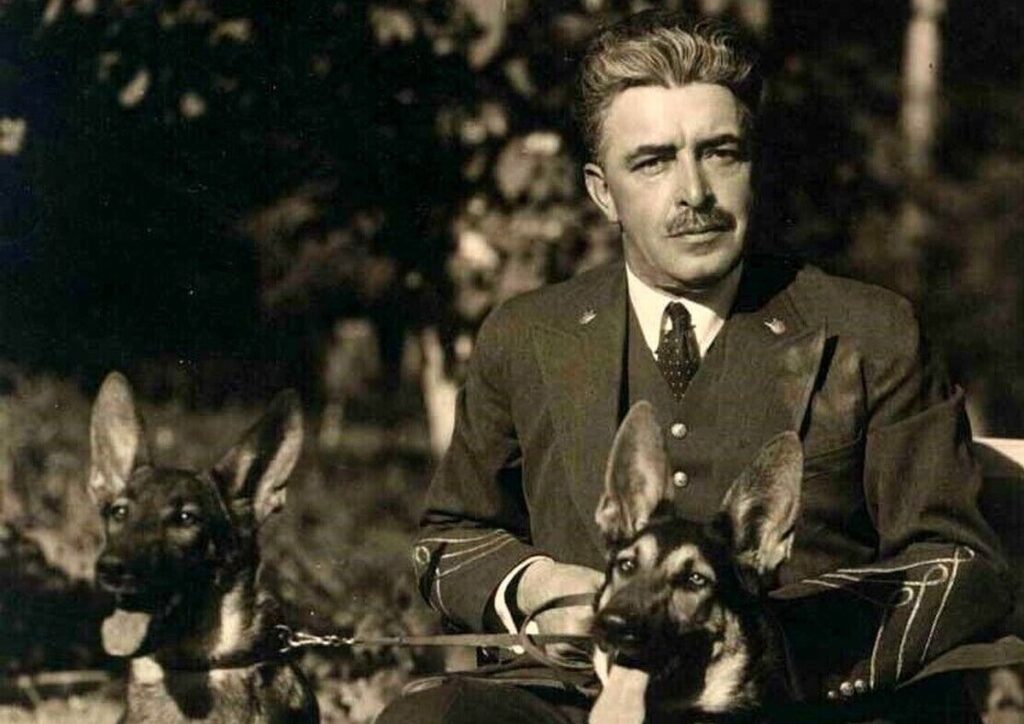

Teymourtash: The Power Broker Behind Reza Shah

There are people who are analytical smart. They’re great logical thinkers, decision makers and problem solvers.

Some are street smart. People who can navigate real-world problems and find instant solutions.

And there are those who have a high emotional intelligence. They can build effective relationships, make connections and navigate people to get what they need.

Teymourtash was all three.

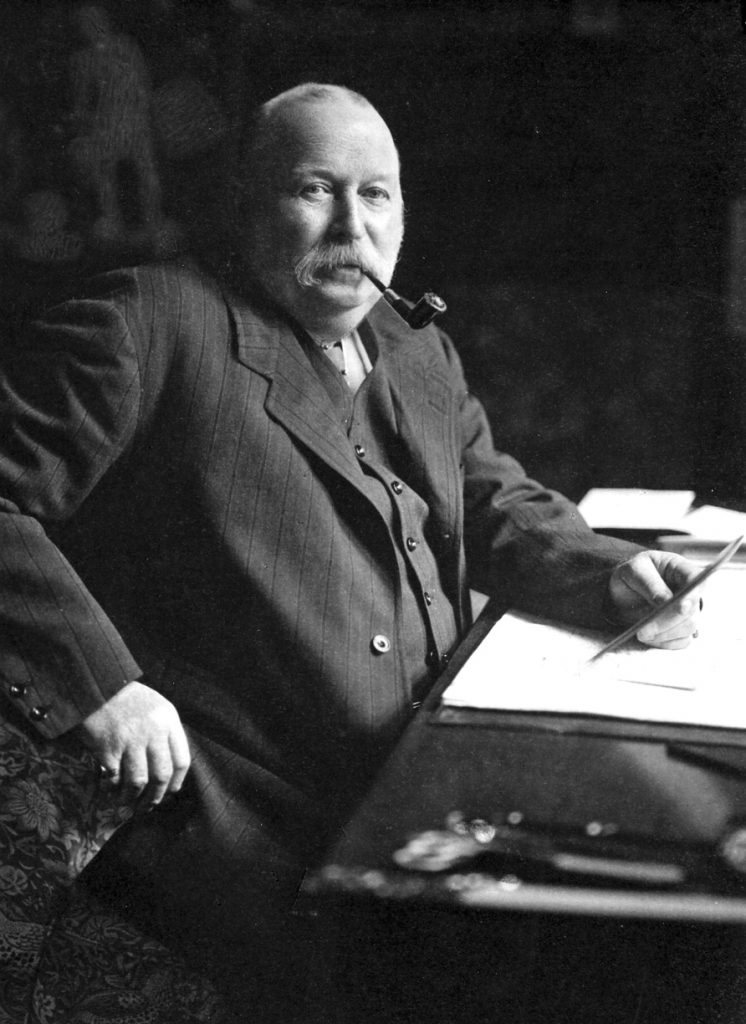

Abdolhossein Teymourtash was born into power. His family had land, wealth, and influence in Khorasan. At a young age, his father sent him off to Russia to a military school, where he picked up Russian, French, and all the modern Western ideas brewing around the globe. By the time he came back to Iran, he wasn’t just another feudal kid—he was ambitious, sharp, and ready to climb.

He first stepped into politics through the 2nd Majlis. Even though he was too young to qualify. He did so by getting the trusted individuals of his province to sign a document saying he was 30. And just like that, he was in. That set the tone for his entire career: clever, strategic, and always knowing how to bend the system in his favor.

You may remember that after the Second Majlis refused to cave to Russian pressure and fire Morgan Shuster in 1911, the Russians forced the government to dissolve the parliament. Out of a job, Teymourtash returned to Khorasan, where he became the commander of the province’s army.

Despite this setback, his political ambitions never wavered. He found a way back. Teymourtash secured a seat in every subsequent Majlis, proving himself an expert at navigating Iran’s shifting power structures. He even teamed up with Moddares to build the Reformist Party, advocating for stronger governance and national unity.

Then he met Reza Khan.

How Teymourtash Became Reza Shah’s Most Trusted Advisor?

At the time, Reza Khan was a military guy on the rise, and Teymourtash saw exactly where things were headed. He bet on Reza Khan, backed him in the Majlis, and helped him climb the ladder.

When Reza Khan pulled off his military coup, Teymourtash was right there, paving the way for him to take power.

When Reza Khan pushed to turn Iran into a republic, Teymourtash was one of the few Majlis members who stood by him. He even parted ways with his old ally, Moddares, and threw his full weight behind the prime minister … And the soon-to-be king liked that.

He respected Teymourtash because of his military background, but his loyalty was what brought him into the inner circle.

Once Reza Khan became Reza Shah, Teymourtash was rewarded handsomely. He became Minister of the Court—basically, the second most powerful man in the country. If something big was happening, Teymourtash was behind it. He shaped policies, pushed modernization, handled negotiations, and even organized Reza Shah’s coronation. He was untouchable.

With Teymourtash leading the charge, Iran expanded its demands for a new agreement.

The Battle Over Iran’s Oil: Britain vs. Teymourtash

Instead of the 16% share of net profits, Iran now wanted 25%. The government also demanded two seats on the board of APOC and veto power over major decisions. On top of that, Iran wanted to break Britain’s monopoly over the industry, allowing other countries—such as the United States—to enter as potential investors and business partners.

Reza Shah was confident. He believed Iran was in a strong position to secure a better deal.

But reality proved far more complicated.

The D’Arcy agreement had been signed three decades earlier, at the turn of the century. It belonged to another era. Since then, the balance of power had shifted dramatically in Britain’s favor. The British had expanded their global influence after World War I, cementing themselves as a superpower. They had also diversified their oil sources, extracting from multiple countries beyond Iran.

They had the upper hand. And that was precisely why they were open to renegotiation.

They knew they could secure an even better deal …for themselves.

At the negotiation table, neither side was willing to concede. Teymourtash presented the Shah’s demands and refused to back down. The British, meanwhile, had their own agenda. They wanted to reduce Iran’s share even further, restructuring the profit-sharing model so that Iran would receive a fixed payment per ton of oil extracted.

What was supposed to be a negotiation quickly turned into a battle of egos, and developments stagnated.

During all of this, something else was happening as well.

The King was losing confidence in Teymourtash.

How Shah Became Suspisious of Teymourtash?

Throughout the negotiation with the British, Teymourtash showed a great deal of resilience. But his influence wasn’t in this one issue. He was Iran’s chief envoy on foreign trips, the architect of key agreements, and the primary handler of the country’s foreign relations. He was smart, elegant, and charismatic, fluent in French and Russian—which made him stand out on the international stage.

The Shah himself had once told his inner circle, “Teymourtash’s words are my words.”

But naturally, that kind of influence didn’t go unnoticed. The foreign press began to speculate: was it really Reza Shah pulling the strings, or was Teymourtash the true power behind the throne?

Some outlets painted Reza Shah as nothing more than a hillbilly soldier, a man with no real understanding of politics, molded and guided by Teymourtash—the mastermind politician teaching the king basic diplomacy and even personal etiquette.

It was a dangerous narrative. And it came at Teymourtash’s expense.

Reza Shah Burns the Oil Contract

In November 1932, Reza Shah, annoyed by the slow progress in the negotiations, scolded Teymourtash and asked him to bring the oil dossier for his review. Once the dossier was brought to him, he wasted no time in throwing the document into the fire, burning it to ashes.

The file contained the agreement signed by Mozaffar al-Din Shah a quarter of a century earlier—the contract between the British Empire and the Kingdom of Persia, the deal that had bound Iran’s most valuable resource to foreign hands.

Reza Shah had erased the biggest economic contract in his country’s history.

“Iran exits the colonial oil contract enacted by the weak Qajar dynasty” … On November 12th, this was the main headline on all important newspapers of the country.

To control the narrative, the government quickly organized celebrations, framing the move as a bold, patriotic stand against foreign exploitation. They assured the public that a better, fairer deal with the British was on the horizon—one that would finally prioritize the interests of the Iranian people.

The streets filled with cheers. But behind closed doors, uncertainty loomed. No one knew this was coming. Not the British. Not even Teymourtash.

But Reza Shah was king, so his government had no choice but to comply.

The Fall of Teymourtash: Political Betrayal or Conspiracy?

This event also marked the unofficial end of Teymourtash’s influence in Iran.

Less than a month after Reza Shah’s public scolding, on December 24th of that year, Teymourtash was removed from his post and arrested on charges of bribery and embezzlement.

Some say the real reason for the falling out was simple: Reza Shah’s ego. The foreign press articles portraying Teymourtash as the true power behind the throne were too much for the Shah to tolerate. He was arrogant and couldn’t handle anyone stealing the spotlight.

Another theory suggests Reza Shah was thinking about the future of his dynasty. He was aging, and his heir, Mohammad Reza, was still just a child. Knowing Teymourtash’s boldness and political savvy, the Shah feared he might orchestrate a coup against the young prince and seize power for himself.

But for others, the conspiracy goes even deeper.

Was Teymourtash a Russian Agent?

In late 1932, after another round of fruitless negotiations with the British, Teymourtash returned to Iran to report directly to the Shah. His route took him through Russia, where he made a stop in Moscow and allegedly held secret meetings with Soviet officials, including War Minister Kliment Voroshilov. Rumors circulated that someone had stolen a briefcase containing sensitive documents about the oil negotiations during the trip.

News of Teymourtash’s Moscow meetings reached Reza Shah from two separate sources: first, from the Iranian ambassador in Moscow, and then from British intelligence agents. Teymourtash had studied in Russia and maintained deep personal ties to the country, which only fueled the Shah’s growing suspicions. Some say right there was when he began to believe Teymourtash was a Soviet spy, working to re-establish Russian influence in Iran under the guise of diplomacy.

But the final theory takes it to another level.

Did Britain Orchestrate Teymourtash’s Downfall?

It suggests that everything—the newspaper articles, the stalled negotiations, even the reports of Teymourtash’s meetings with the Soviets—was part of an elaborate British campaign to remove him from power. Frustrated by his stubbornness at the negotiating table, the British may have orchestrated his downfall, believing that without Teymourtash, they could secure a more favorable deal.

But no matter which theory you believe, one thing is certain: Teymourtash was done.

The architect of the Pahlavi dynasty—the man who was once the second most powerful figure in the country—was now rotting in jail on fabricated charges.

The League of Nations and Iran’s Fight for Oil Independence

As all of this was happening, the British, angry over Reza Shah’s action, took their case to the League of Nations – the predecessor to the United Nations that was formed after World War 1.

They wanted the international community to reprimand Iran and give them a win in their negotiations. Both countries sent delegations to make their case but the league refused to weigh in and asked the parties to continue the negotiations and find new ground.

This time, it was the British that sent a team to Tehran.

During the past rounds of negotiations, something had become clear to the British: the only person who could truly make or break any agreement was Reza Shah himself. The ministers, the envoys, the negotiation teams—they were all just intermediaries. The Shah held the real power. His word was all that mattered!

So, the British decided to bypass the formalities and approach Reza Shah directly.

Reza Shah Caves: Iran’s Oil Future is Sold to Britain

And then something strange happened.

When the British presented their terms directly to him, the Shah caved.

He blamed his ministers for being too rigid, accusing them of failing to consider the British perspective or appreciate the “good” Britain had done for Iran. Then, in a move that shocked even his closest advisors, Reza Shah accepted nearly all of Britain’s demands.

He abandoned Iran’s bid for veto power and the additional seats on the APOC board. He even agreed to extend the contract until 1993—ensuring British control over Iran’s oil for decades to come.

In return, Britain guaranteed Iran an annual payment of at least £975,000 and agreed to increase Iran’s share of oil profits from 16% to 20%. But as before, they continued manipulating their accounting, falsifying documents, and using financial loopholes to minimize Iran’s actual earnings.

Throughout this entire ordeal, Reza Shah had presented himself as the fierce protector of Iran’s interests, chastising his ministers for failing to secure a better deal. He railed against their incompetence, frustrated by their inability to deliver results.

But in the end, it was Reza Shah himself who unraveled all the progress his team had made. He singlehandedly forced Iran into another imperial contract with the British, surrendering the very leverage he had fought so hard to gain.

The 1933 Oil Agreement: Victory or Another Defeat for Iran?

Despite all of this, the Shah’s team worked hard to present the new agreement as a triumph for the monarchy, the people, and the nation as a whole. State-controlled newspapers celebrated how “The King had masterfully crafted a new agreement” and how “Iran’s dignity has been restored on the international stage, and foreign countries once again respect the nation.”

But the truth was far from the headlines.

The 1933 agreement was no different from the original deal signed between Mozaffar al-Din Shah and William D’Arcy. It had the same exploitative terms, the same imbalance of power—only one thing had changed:The Anglo-Persian Oil Company was renamed to the Anlgo-Iranian Oil Company.

2 Responses