Nowruz, translating to “new day”, is the celebration of the Persian New Year. It’s observed on the vernal equinox, typically around March 20th or 21st. This ancient festival, with roots extending over 3,000 years, symbolizes renewal and the rejuvenation of nature as it marks the official start of Spring.

Celebrated by millions across regions such as Iran, Central Asia, and parts of the Middle East, Nowruz encompasses various customs and traditions that emphasize themes of rebirth and prosperity.

Historically, it has also been the cornerstone of many of Iran’s major political events. Reza Shah originally wanted to turn Iran from a monarchy into a republic on the eve of Nowruz 1924. The official name change of Persia to Iran took place on Nowruz in 1925. The oil nationalization bill also passed the Majles on Nowurz of 1951. (we haven’t gotten to that story yet in our podcast)

So let’s look at Nowruz, its history, meaning and all the traditions around it.

Origins of Nowruz

Various perspectives exist on its origins, with some attributing it to Jamshid, the fourth king of the mythic Pishdadian dynasty. Mythological accounts suggest that Jamshid, known as “Yima” in the Avesta, was blessed with divine glory and led a battle against Ahriman, the embodiment of evil. After vanquishing Ahriman, prosperity returned, and trees that had withered blossomed anew. People celebrated the occasion by planting seeds—a tradition that endured through the centuries.

Another legend recounts how Jamshid, travelling the world, arrived in Azerbaijan and ascended a bejewelled throne at sunrise. The brilliance of his throne dazzled the people. They named the day “Nowruz,” or “New Day,” and celebrated it as a festival. His name later incorporated the word “Shid,” meaning “radiance” in Pahlavi, cementing his association with the holiday.

A different perspective ties Nowruz to the completion of creation. According to some beliefs, God finished the creation of humans and all living beings on the first day of Farvardin, the opening month of the Persian calendar. In gratitude, humans celebrated with prayers and festivities. Another interpretation connects Nowruz to the return of the spirits of the deceased (Farvahars) to the earthly realm on the first day of Farvardin. The Avesta describes how the souls of the righteous visit their loved ones. In preparation, families engage in house cleaning, symbolizing their readiness to welcome them.

The Science Behind the Celebration

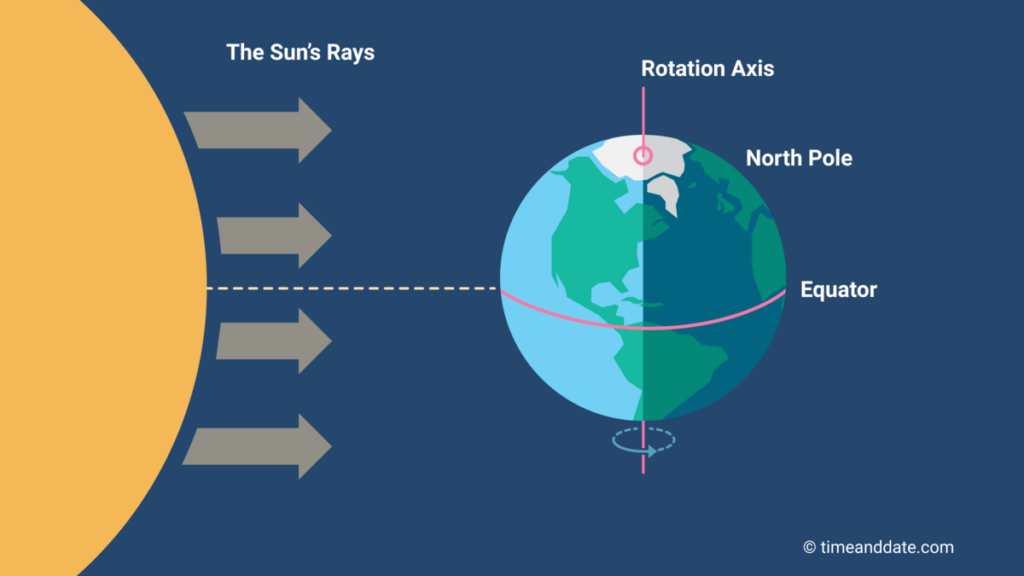

The vernal equinox is a celestial event that occurs each year around March 20 or 21. It’s when the Sun, in its vast journey across the sky, crosses directly over Earth’s equator. On this day, neither the Northern nor the Southern Hemisphere leans toward the Sun. This results in nearly equal hours of daylight and darkness across the entire planet.

This happens because Earth is tilted on its axis at 23.5 degrees, an angle that gives us the changing seasons. Throughout the year, as Earth orbits the Sun, different parts of the planet receive varying amounts of sunlight. But during the vernal equinox, that tilt aligns in such a way that sunlight is evenly distributed between both hemispheres. It marks the official beginning of spring in the Northern Hemisphere, a time when days start growing longer, temperatures rise, and life begins to awaken from winter’s slumber.

Nowruz Across the World

Nowruz is observed in numerous countries, each adding its unique customs to the celebration:

- Iran: As the origin of Nowruz, it is the most significant national holiday, celebrated with various rituals and festivities.

- Afghanistan: Known as “Nawroz,” it includes public celebrations, special meals, and cultural performances.

- Azerbaijan: Celebrated as “Novruz,” it involves public dancing, folk music, and sporting competitions.

- Central Asian Countries: Nations like Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan observe Nowruz with various traditions, including public celebrations and cultural events.

- Iraq: Particularly among Kurdish communities, Nowruz is celebrated with traditional music, dancing, and public festivities.

- Turkey: Known as “Nevruz,” it is celebrated with various customs, especially among Kurdish populations.

- India and Pakistan: Observed by Parsi communities, descendants of Zoroastrian Persians, with cultural events and gatherings.

UNESCO Recognition as an Intangible Cultural Heritage

In recognition of its cultural significance and the traditions associated with it, Nowruz was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009.

Furthermore, in 2010, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed March 21 as International Nowruz Day. It was a decision that acknowledged Nowruz’s importance in promoting peace and solidarity across different cultures.

Nowruz in Iran

Historical records on the celebration of Nowruz during the Achaemenid period remain scarce, though scholars infer from Persepolis reliefs that Nowruz was observed as a grand occasion where subject nations presented gifts to the Persian king. Information about the festival during the Parthian era is limited, but it is suggested that Greek influence led to a temporary decline in Persian customs, which were later revived.

During the Sassanian period, Nowruz was a major celebration lasting between six and thirty days. The sixth day of Farvardin, known as “Greater Nowruz,” was associated with Khordad, a sacred divine figure. Followers of Zoroastrianism believed that the prophet Zoroaster was born on this day and that he engaged in divine communion, making it a sacred occasion. The Sassanian kings marked Nowruz with grand festivities, dedicating the first five days to public audiences and addressing people’s needs, while the latter days were reserved for private celebrations among the elite.

A popular custom during this era involved sprinkling water on one another in the early morning of Nowruz, along with the exchange of sugar as a token of sweetness for the coming year. The deep cultural attachment of Iranians to Nowruz ensured its survival even through the Islamic era, despite some rulers’ initial reluctance. Eventually, the tradition of presenting gifts to rulers led even the Arab caliphs to embrace the celebration, securing its continuity through centuries of political and religious transformations.

Celebrations and Customs

Nowruz, the Persian New Year, is celebrated with rich traditions that span before, during, and after the holiday. These customs emphasize renewal, family, and nature.

Pre-Nowruz Traditions: Chaharshanbe Suri

Before Nowruz, Iranians celebrate Chaharshanbe Suri, the Fire-Jumping Festival, on the last Wednesday night before the new year. People jump over bonfires while chanting phrases that symbolize purification and renewal. The flames are believed to burn away negativity, preparing individuals for the new year with positive energy.

Nowruz Day Festivities

Nowruz itself is marked by family gatherings and festive meals. Visiting loved ones is an essential custom (Eid-didani) for reinforcing social bonds and spreading joy.

A central element of Nowruz celebrations is the Haft-Sin table, an arrangement of seven symbolic items whose names start with the Persian letter “س” (pronounced “sin”). Each item represents a different hope or aspect of life for the new year:

- Sabzeh (سبزه): Sprouted wheat, barley, or lentils, symbolizing rebirth and growth.

- Samanu (سمنو): A sweet pudding made from wheat germ, representing power and strength.

- Senjed (سنجد): Dried oleaster fruit, signifying love.

- Seer (سیر): Garlic, symbolizes medicine and health.

- Seeb (سیب): Apples, represent beauty and health.

- Somāq (سماق): Sumac berries, embodying the sunrise and patience.

- Serkeh (سرکه): Vinegar, denoting age and wisdom.

Additional items like a mirror, candles, painted eggs, and a bowl of water with goldfish are often included to enhance the display, each carrying its own symbolism related to life and renewal.

Post-Nowruz Traditions: Sizdah Bedar

On the 13th day of Nowruz, Iranians observe Sizdah Bedar, also known as Nature Day. Families go outdoors for a picnic, enjoying fresh air and celebrating the arrival of spring. This day is believed to ward off bad luck, and a common tradition is to release Sabzeh (sprouted wheat or lentils) into running water, symbolizing the release of negativity from the past year.

These Nowruz customs reflect the themes of renewal, joy, and connection with nature, making it one of the most cherished celebrations in Persian culture.

Nowruz in a Nutshell

Nowruz is more than just a New Year celebration—it’s a tradition that has brought people together for thousands of years. It’s about renewal, family, and the changing of seasons, connecting millions across different cultures. Whether through fire-jumping, festive meals, or spending time in nature, Nowruz reminds us of the importance of tradition and community.

If you’re interested in exploring Persia’s modern history and how these traditions have evolved, check out our podcast, The Lion and the Sun. We dive into the stories that shaped Iran and its place in the world today.

Listen to us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

One Response