This is the transcript for Book One, episode 5 of The Lion and the Sun podcast: Battle of Tehran. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

Grand National Council: Shah’s Scham Parliament

Four months after the bombardment of the parliament, the news of uprisings in various Persian cities had reached the ears of Mohammad Ali Shah. He knew that his military wouldn’t be able to handle the numerous protests happening in Persia’s north, west and south all at once. Other actions must have been taken to calm the angry constitutionalists. That’s why in November 1908, the king announced that while the parliament would not be re-opened, he planned on forming a “Grand National Council” in its place.

The Grand National Council was a legislative branch that had no power of its own. All the 50 members of the chamber were to be named by the Shah himself. He had the executive right to shut down the council anytime he pleased. The national council was in charge of passing laws. Yet all the motions approved by the council had to be ratified by the king before being signed into law.

After the establishment of the chamber, Mohammad Ali Shah asked the newly constructed council to redraft the constitution. The king, proud of his decision and feeling safe from the mutiny of his enemies, went back to living his lavish lifestyle. Despite Shah’s directions, the new council failed to generate the authority that the previous parliament possessed. Both the constitutionalists and the monarchists refused to take the branch seriously. They saw it as a temporary solution not meant to last.

The failure of the Grand National Council even worried Iran’s influential foreign players. The Russian and British Empires were losing faith in Mohammad Ali Shah’s ability to control its people. They were fearful of the rising unrest across the country.

In April 1909, a memo drafted jointly by the British and the Russians arrived in the hands of Mohammad Ali Shah, the ruler of Persia. The words contained in the memo were harsh and direct. They warned the Shah that his reign was on the brink of collapse and that the Anglo-Russian powers weren’t confident in the king’s ability to maintain control of the country.

The ominous message left the Shah with no choice but to come up with a plan to reopen the parliament. Little did he know that the fate of his kingdom was already sealed.

As the sham council was busy preparing for a rushed election for another attempt at a parliament, two well-trained armies of Iran’s fiercest freedom fighters were on their way to the capital. Their determination and unwavering spirit set the stage for a fight that would determine the future of Persia.

As the clock ticked away, the tension mounted, and the fate of the kingdom hung in the balance.

All sides were getting ready for the battle of Tehran.

Sepahdar Leads the Northern Rebel Army to Tehran’s Gates

After liberating the province of Gilan, the northern army consisting of Caucasus volunteers, Armenian fighters and northerners, headed toward Tehran to capture the capital city. The army was led by Mohammad Vali Khan Khalatbari, also known as Sepahdar. A military commander and politician from the Mazandaran province.

Sepahdar was a wealthy and powerful man who was initially an ally of the monarchy. He was the minister of post and telegraph as well as the ruler of Gilan for extended periods. He was amongst the most influential people in the region. His military acumen and statesmanship placed him among the prominent fighters in the country, so much so that he was tasked with capturing the northwestern province of Azerbaijan during the rebellion of Bagher Khan and Sattar Khan.

After the siege of Tabriz, Sepahdar escaped to the north of Iran, where he expressed regret for his previous actions and joined the constitutionalist army of Gilan. His motives were met with skepticism by the northerners. They were wary of his desire to expand his power by taking advantage of the constitutionalists’ momentum. Despite this, Sepahdar soon proved himself to be a military genius. With exceptional strategic abilities, he quickly rose to become one of the movement’s most influential leaders. Ultimately, he was put in charge of heading the army toward the capital.

On May 5th, 1909, the nationalists of Gilan entered Qazvin, a city close to Tehran and took it back from the forces of the monarchy. The constitutionalists’ army consisted of a few hundred soldiers equipped with weapons made or brought by the Russian social democrats. From Qazvin, the army devised its path to Tehran. While recovering in a nearby city, a high-ranking Russian embassy official met with the leaders of the rebellion to negotiate a cease-fire.

He pleaded that given the Shah’s recent decision to reconvene the parliament and the nation’s progress towards a constitutional monarchy, further conflict was unnecessary.

The leaders of the resistance movement contemplated the proposal. Not all the constitutionalists were on board with the march to Tehran. Some of the Tabriz fighters were increasingly concerned about the possibility of Russian military intervention. They warned that if the conflict continued, the risk of foreign invasion would increase dramatically. This would put the country in danger of suffering the same fate as Tabriz had just a few months earlier. The thought of reverting to foreign domination weighed heavily on the minds of the fighters. They knew that time was running out to resolve the conflict before it was too late.

But despite the difference of opinion, most high-ranking constitutionalists agreed that the word of Mohammad Ali Shah was not to be trusted. That the only path to democracy was through their armed forces.

Bakhtiari Riders Join the Capital Showdown

In the south, on May 21st, the Bakhtiaries left Isfahan and set course towards the capital. The army was led by Sardar Asad Bakhtiari.

Ali-Qoli Khan Bakhtiari was a political and military leader who was Tehran’s head of security during the reign of Nasir-Al-Din Shah. He was later appointed as the head of the Bakhtiary Riders by Mozaffar-al-din Shah.

After the establishment of the parliament in 1906, Sardar Asad decided to travel to Europe for eye surgery. During his stay in Europe, he spent much of his time studying and translating foreign literature. After hearing about the bombardment of Majlis, he was called back to Iran to help the Bakhtiarys fight for the constitution.

Sardar Asad’s return to Iran was met with great enthusiasm by the constitutionalists. His military experience and political acumen made him an invaluable asset in the fight against the monarchy. He immediately began to organize the Bakhtiary riders and worked tirelessly to strengthen their position in the movement.

While the bulk of Bakhtiaries were riding with Sardar Asad, their pro-monarchy fraction, was ordered by the Shah to stand against their fellow brothers and prevent them from reaching the city. Sardar Asad sent an envoy to try to negotiate and convince the others to join their cause. But after the talks broke down, they opted to alter their route to bypass the blockade.

West Meets North: The Constitutionalist Armies Converge

The riders went around to the city of Robat Karim and from there joined the northern army camping in the region. With the combined forces of the northern and western armies, on June 24th, 1909 they started their march toward Tehran.

To intimidate the resistance army, Russia dispatched a regiment of infantry and canons to Iran. Their troops scattered across the cities of Anzali and Qazvin – both previously captured by the northern army. The objective of this move was to push the constitutionalists into a defensive stance, hindering their capacity for offensive assaults. The Russians were also hoping to play into the constitutionalist’s fear of a foreign invasion. They wanted to intimidate them into backing down.

On the borders of the capital, Sardar Asad and Sepahdar, sent a letter to the Shah, listing their three demands for preventing an all-out war in the capital.

First, they demanded the immediate dismissal of all Russian troops from Iran’s soil.

Second, they called for the designation of key ministry positions by local tribes, who had a better understanding of the country’s needs and demands.

Finally, they insisted on the immediate firing of some of the Shah’s closest allies. Who they believed were responsible for the current political crisis.

Maryam Bakhtiari’s Covert Mission in Tehran

Before sending in the demands, the Bakhtiary forces had managed to secretly smuggle one of their agents to the capital. Maryam Bakhtiary was from one of the most noble families in Iran and a well-known Bakhtiarty activist. Known for her significant role in Iran’s women’s rights movements, Maryam had learned military strategy from her father, a clan leader.

Furthermore, she was instrumental in persuading Sardar Asad to return to Persia and join the resistance forces.

Leading up to the battle, Maryam had managed to gather a few of the Bakhtiary riders, sneak into Tehran, and take shelter in their ancestral home near Parliament. The plan was to use this house as an unofficial stronghold. They wanted to strengthen the areas near Majlis and use it as an inside advantage. They wanted to fight the Cossack brigade and Shah’s army on two fronts.

The two leaders waited with bated breath, hoping that their demands would be met and that they could avoid a bloody conflict that could plunge the country further into chaos.

But Shah refused the demands.

The battle of Tehran commenced shortly after.

Shah Braces for Battle

After rejecting the demands, Mohammad Ali Shah summoned his army to defend the city. The military units fortified the gates with cannons and armed soldiers, preparing for the arrival of the nationalist army. As the preparations were made, an eerie silence enveloped the city. The people and the army, the constitutionalists and the monarchists, the peasants and the nobles, awaited the onslaught.

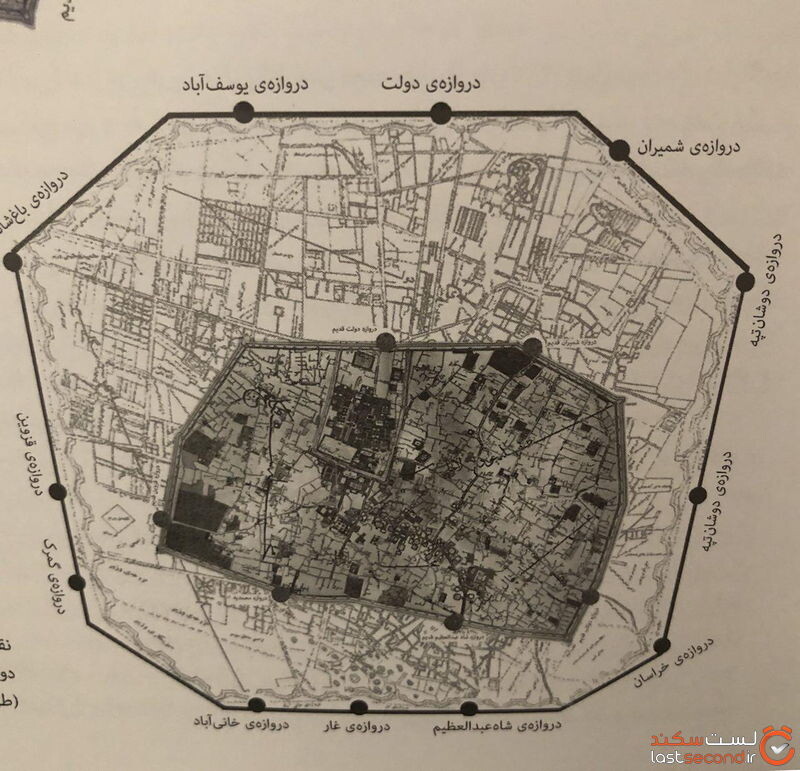

In 1909, Tehran boasted a total of 12 gates that served as the official entry points to the capital. The city’s walls and infrastructure were constructed around these gates, which had been first erected during the Safavid dynasty. During the Qajar reign, the existing gates were dismantled to accommodate the city’s expansion.

One of the gates, the Behjat Abad Gate, situated in the northeast, served as an early battleground between the monarchy and the resistance. As the two armies converged on the gate, they encountered resistance from the cossack brigade, the Russian-trained part of the army.

Despite the Shah’s army’s best efforts to disperse the nationalist forces by firing their cannons, the fighters persisted in their struggle with unwavering determination. After a year of continuous resistance against multiple waves of imperial attack, the Northern and Western armies had honed their skills and developed a vigilant approach. Boasting over 3,000 well-trained soldiers, they posed a significant challenge to the monarchy.

Finally, on July 13th, their resilience paid off. The armies finally broke down the Behjat Abad gate, paving the way for their entry into the city.

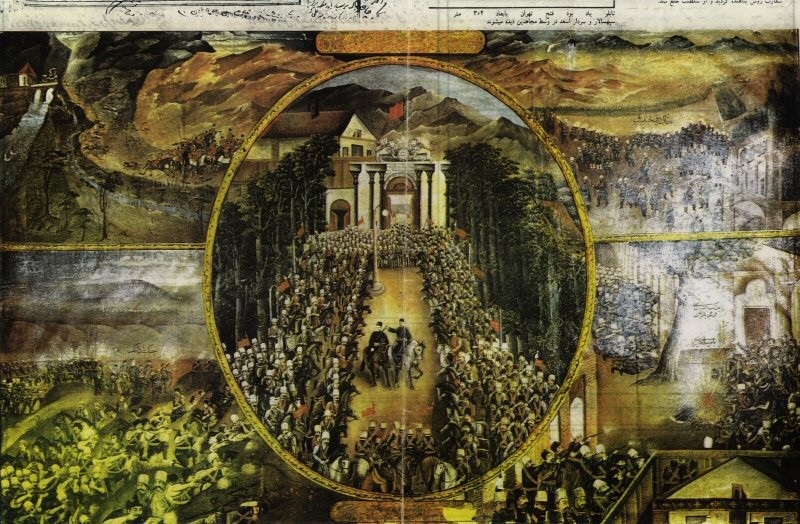

The Conquering of the Capital

Despite the British and Russian’s continuous warnings of a looming attack, Shah’s army seemed unable to control the outbreak. They were demoralized, disorganized, and worn out by the year-out campaign against the constitutionalists. Even though the two opposition armies had never worked or even trained together, their discipline was unmatched and their energy was unstoppable.

As the news of the breach spread, Maryam Bakhtiary, the insider within the capital began a skirmish warfare near Baharestan and the parliament building, trying to secure the area. She was soon joined by the resistance army and they soon gained control of the entire area. Within a few days, the constitutionalists controlled most of the northern neighbourhoods and the city center. They established a headquarters in Sepahsalar mosque, the stronghold near the parliament, and began strategizing their next steps.

Shah, his entourage, and his remaining forces which amounted to about 500 soldiers, took shelter in one of Qajari strongholds to regroup but the nationalists were adamant in their pursuit. There was no way out for the Persian king.

After extended negotiations, Mohammad Ali Shah, demoralized by the constant defeats, took shelter in the Russian embassy to be under the joint protection of the northern and southern superpowers.

On July 15th, the nationalists regrouped in the abandoned Majles building. They announced the abdication of Mohammad Ali Shah and the official end of his reign in Persia.

The king who wanted the glory and power of his grandfather was now the first abdicated monarch of his house.

With the capital in their control, the resistance army wanted to bring back normalcy to the city. The first order of business was preventing the city’s descent into chaos. The opposition leaders made sure that there would be no looting, no damage to people’s property, and no revenge on the soldiers fighting for the other side. The nationalists were also quick to assure the safety of foreign diplomats and residents to maintain a peaceful relationship with other countries.

After the abdication of Mohammad Ali Shah, the opposition planned to end the Qajar rule altogether. They wanted to terminate the dynasty and move forward with another political system. But fear of Russian retaliation made them second-guess their decision.

The reason for this fear dates back to a piece of document signed 87 years before the battle of Tehran.

The Dynasty Clause: Fine Prints of the Turkmenchay Treaty

On February 21st, 1821, after a series of Russo-Persian wars, the Turkmenchay treaty was signed to ensure peace between the two countries. In this treaty, the Qajars gave up large parts of Persia to the Russians. In turn, Russia promised to support and recognize the rule of the Qajar dynasty and Qajar dynasty only. Under Article 7 of the Treaty, the Russian government recognized the succession to the throne to lie in the direct male heirs of ʿAbbās Mīrzā, son and heir-apparent to Fatḥ-ʿAlī Shah. Even though the heir-apparent died before the king himself, Russians interpreted this article to imply that while individual rulers could be changed, the continuity of the dynasty itself must not be affected.

This meant that if the constitutionalists went forward with ending the dynasty, it could trigger the Russians and cause another war in the northern regions. After much deliberation, the opposition decided to name Mohammad Ali Shah’s son, Ahmad Mirza as the future king of the country.

A Broken Throne: The Rise of a News King

At the time of the decision, Ahmad Mirza was only 12 years old. Naturally, Mohammad Ali Shah and queen consort, Malakeh Jahan, were hesitant about leaving him behind by himself. But the constitutionalists guaranteed the son’s safety. They agreed to name Ażod-al-molk, the Qajar tribe leader, and Ahmad Mirza’s uncle as his regent.

Azod-al-molk was known for his wisdom and honesty, and his leadership helped to restore trust and improve relations. To govern the country until the new parliament was formed, a group of elder statesmen established a directorate. They appointed the grand-vizir and other cabinet members of the young king on his behalf. They also purged the court of undesirable elements and dismissed numerous unworthy tutors, officials, and corrupt courtiers.

The new temporary directorate also brokered a new peace deal with the Russians. Under the new agreement, the cossack brigade was allowed to remain active in the country to control the safety of the capital. In turn, the Russians would recognize Ahmad Shah as the new king of Persia.

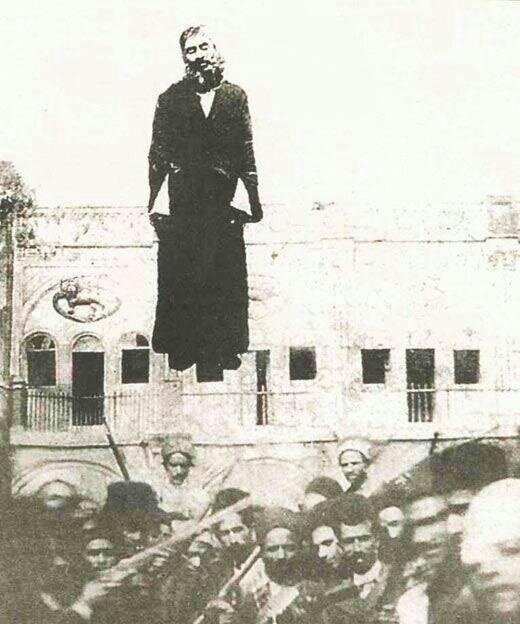

The Bitter End of Sheikh Fazlollah Nuri

Having resolved the external crisis, the directorate intended to conduct trials for Mohammad Ali Shah’s allies. But ultimately granted national amnesty to all those accused of opposing the constitutionalists. Only those found guilty of high crimes faced accountability and were sentenced to execution by a specialized tribunal.

One of the executed individuals was Sheikh Fazlollah Nuri. The clergy who early on had a significant role in establishing the parliament but had become a fierce enemy of democracy in later years. During the final months of Mohammad Ali Shah’s reign, Nuri went as far as issuing a fatwah against those daring to protest against the king’s word.

Nuri’s fate met a bitter end at Tup Khaneh square, where he was hanged in front of a breath-held crowd. For the very first time, individuals bore witness to the fall of one of their once-revered clergys, a chilling spectacle that etched into the public consciousness.

Young Ahmad Shah: A New Hope for Persia?

With everything going back to normal, on July 16th, 1909, Ahmad Shah was officially crowned the next king of Persia.

After the coronation of his son, Mohammad Ali Shah was forced to leave the country he once ruled. On September 9th of that year, he left Tehran for Odesa, which was then part of the Russian empire.

Upon his arrival, he was gifted a palace by the Tzar of Russia, which became his home for several years. Despite being in exile, Mohammad Ali Shah attempted to lead a relatively normal life. He often visited the city’s attractions, including the racetrack, theatre, and bathhouse.

Despite this return to normalcy, the exiled king remained determined to reclaim his throne. In 1911, he even launched an unsuccessful invasion of Iran.

After his defeat, he returned to Russia. But with the ongoing Russian revolution, he was forced to move to Turkey, where he spent a brief period before ending up in Italy. In Italy, he remained in exile until his death in 1925.

Russian Influence: Watchful Eyes on the New King

Before his abdication in 1907, Mohammad Ali Shah had appointed Konstantin Smirnov as his son’s personal tutor. Smirnov was an ex-captain of the Russian army. After retirement, he travelled to Iran to prepare the young prince for his royal duties as the future king.

The constitutionalists thought of Smirnov as a Russian agent trying to brainwash the young king. So they decided to kick him off the court. The Russians objected to this decision, arguing that Smirnov was just a tutor doing his job. They asked the directorate to rescind his firing. They went as far as offering to reduce their military presence in the country by half if Smirnov was allowed to stay. Which in itself was a clear sign of Smirnov’s allegiance.

The offer was enticing and hard to resist. The reduction of Russian presence in the military meant more autonomy for the Persians. But the constitutionalists argued that the damage of a Russian agent having the ear of the shah was far worse than the presence of a few thousand extra soldiers. Ultimately they rejected the offer and dismissed him from the position. The responsibility of educating the young king was then entrusted to individuals whose primary objective was to transform Aḥmad Shah into a truly constitutional monarch and hopefully prevent another coup against the democracy.

Democracy Reborn: Reopening of the Majles Parliament

With Ahmad Shah as the king, the directorate went ahead with preparing the country for the reopening of the parliament. This new parliament differentiated from the previous one in many ways. Firstly, the members were no longer elected based on their societal class or the unions they belonged to. There were no financial prerequisites for becoming members and even people from far villages and nomad tribes could join the chamber.

On November 15th, 1909, the second national assembly was officially opened. After one year, 4 months and 21 days of struggle, the dream of constitutionalists finally came true.

The parliament immediately named Sepahdar, the leader of the northern army as the prime minister of the Shah and Sardar As’ad, the leader of the western army as the minister of the interior.

Ażod-al-molk, the regent, invited Sattar Khan and Bagher Khan, the two heroes of the Tabriz struggles to Tehran. In April of 1910, they arrived in the capital and were met with an unprecedented crowd. People who had come to welcome them and celebrate their contributions to the fight for democracy.

On April 19th, the two heroes visited the parliament and gave a speech in front of the exhilarated members who were in awe of these two greater-than-life figures.

The two leaders delivered a stirring speech that emphasized the unwavering resolve of their people and the success of their movement. It was a moment that signalled a turning point for the country, indicating that they had finally surmounted their challenges. The nation had not only stood up for its beliefs and emerged victorious, but it had also managed to resist the influence of its more powerful neighbours, was able to advance the society towards democracy and brought about lasting change.

For a fleeting moment … it appeared that Persia had left all of its troubles in the past. It seemed that the country was destined to step into a brighter future.

But Reality was poised to burst the dreamer’s bubble.

In the next episode of The Lion and the Sun, we’ll see how the Russian influence would jeopardize democracy once again and how infighting breaks the coalition that once united Persia!