This is the transcript for Part One of a special episode from The Lion and the Sun podcast: Arabistan. The story of Sheikh Khaz’al, a tribal leader who ruled Khuzestan and his clash with Iran’s central government. Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

Iran After World War 1

1922 was a time of transformation for Iran.

The First World War had shattered the country and had left behind a trail of destruction, famine and instability. The mismanagement of the state budget by the Qajar dynasty, the monarchy that controlled Iran, had weakened its finances. Widespread corruption had crippled the government from making any strides in fixing those issues.

Amid this chaos, the central government struggled to maintain control, while some regions operated with near-complete autonomy.

Khuzestan, a land of stark contrasts, stretched from the rugged Zagros Mountains to the shores of the Persian Gulf. It was a region where the fertile plains along the Karun River, coexisted with scorching deserts. With summer temperatures soaring above 122°F and relentless dust storms, the province’s harsh environment made it a difficult place to live.

But what made Khuzestan valuable was the treasure buried beneath its land: vast oil fields.

The discovery of oil in the early 20th century turned the province into a strategic asset. It attracted foreign interest and investments. This had turned the tribe leader controlling the land into one of Iran’s most powerful players.

For years, this critical province was controlled by an influential Arabic tribe and their powerful leader who had even renamed the province for his own. Arabistan.

An Ominous Message to Khuzestan’s Leader

Sir Sheikh Khaz’al al-Kaʽbi didn’t believe in compromise. He only dealt with absolutes. Only a few years before, he had received a knighthood from the British government. His land was considered an independent territory even by the Qajar kings. He answered to no one, paid no taxes and had the backing of international players. He had full autonomy and was free to do as he pleased.

The previous governments weren’t able to take action against him, fearing that the British would retaliate if they did. But now a letter had arrived at Khaz’als castle. It was from the capital and signed by the new prime minister.

Pay up or face the consequences!

The British had warned Khaz’al that the new prime minister was built differently. That the Sheikh would be better off if he had settled his tab with the government. But Sheikh, confident in his power, decided to dismiss the letter.

It was a decision he’d soon regret.

Sheikh Khaz’al didn’t believe in compromises, but neither did Reza Khan. The new prime minister of the government, now had his sights firmly set on reclaiming Arabistan for Iran.

The Many Tribes and Ethnicities of Iran

Persia was and is home to numerous ethnicities and tribes living across its vast landscape. In the early 20th century, Iran was home to a diverse range of ethnic groups and tribes. Each with its own distinct culture, language, and social structure. Major groups included Persians, who dominated central and urban areas; Azeris in the northwest and Kurds in the west. Lurs, Bakhtiari, and Qashqais roamed the southwest; with Baloch in the southeast and Turkmen in the northeastern plains.

After the fall of the Safavid Empire in 1722, the vastness of Iran’s landscape and the lack of a unified military enabled these many tribes to take control of a part of the land. This move undermined the rule of the centralized government that the Qajar dynasty later embodied.

One of the most prominent of these tribes was the Banu Ka’b tribe which was located in the Khuzestan region. Khuzestan, a province in southwestern Iran, is located along the Persian Gulf and shares borders with Iraq.

Khuzestan: The Oil-Rich Province of Iran

Historically, Khuzestan is often considered the cradle of Iran’s civilization. With ancient settlements dating back to the Elamite civilization around 3000 BC. The region was an important cultural and political center, particularly under the Elamites, whose capital was Susa, one of the oldest cities in the world.

The significance and influence of the Arab tribes in the region was so great that this province was referred to as Arabistan or the Land of the Arabs.

Khuzestan is home to the Karun River, one of Iran’s longest rivers. Karun originates in the Zagros Mountains of the Bakhtiari region and flows through the province before emptying into the Persian Gulf. As mentioned in our first episode, the right to navigate in the Karun was granted to Britain in one of Naser Al-Din Shah’s concessions in 1888. This concession brought the British into contact with the Banu Ka’b tribe in the province.

Banu Ka’b: The Rise of the Arab Tribe in the South

The Banu Ka’b were one of the most prominent Arab tribes in the region of Khuzestan. They trace their lineage back to the Arabian Peninsula and are believed to have migrated to southwestern Iran over several centuries. Particularly during and after the early Islamic conquests. By the 17th century, the Banu Ka’b had established themselves as a dominant tribal force in the region.

During this time, The Banu Ka’b clan was led by Sheikh Maz’al and the local tribe was soon held at the orders of the British Government. This meant that they received a degree of support from the British Government in return for watching out for their interest in this region of Persia.

Nine years later, Maz’al was assassinated by his brother. The exact details about the assassination of this tribal leader is a bit unclear. Some believe that after ten years of maintaining a close bond with his brother, Khaz’al, along with his servants, managed to shoot and kill Sheikh Maz’al as he was boarding his boat. Others say that on the first of Muharram, at sunset, a group hired by Khaz’al attacked Maz’al’s home and killed him along with fourteen members of his family and relatives.

Sheikh Khaz’al was a charismatic leader. He was seen as a dignified, imposing figure. Khaz’al was known for his regal demeanour and his will to fight for what he thought was his. Unlike his brother, Khaz’al believed in absolutes and wasn’t a fan of compromise.

Assassinations and Kin Slaying: Rise of Sheikh Khaz’al

In 1897, Sheikh Khaz’al inherited his brother’s wealth and took control of the tribe and its vast territories. Unlike Maz’al, who had carefully balanced his relations with both Britain and Tehran’s central government, Khaz’al adopted a different strategy. Dismissing the influence of the Qajar dynasty, Khaz’al chose to focus entirely on strengthening his ties with Britain. He solidified his alliance with the southern superpower. His relationship with the British became so close that the Qajar-appointed governor of the province warned the prime minister that unless Khaz’al’s power was reined in, the region risked becoming a British protectorate.

But Atabak, Iran’s then-prime minister, and all the ones after him failed to act accordingly. They all feared Britain’s retaliation toward the fragile Qajari government. The Government went as far as granting Khaz’al the right to collect customs payments at the port of Khoram Shahr. A privilege that Khaz’al took advantage of without ever providing the government with an accounting overview of the fees collected on his behalf.

Foreign Allies: Khaz’al’s British Ties

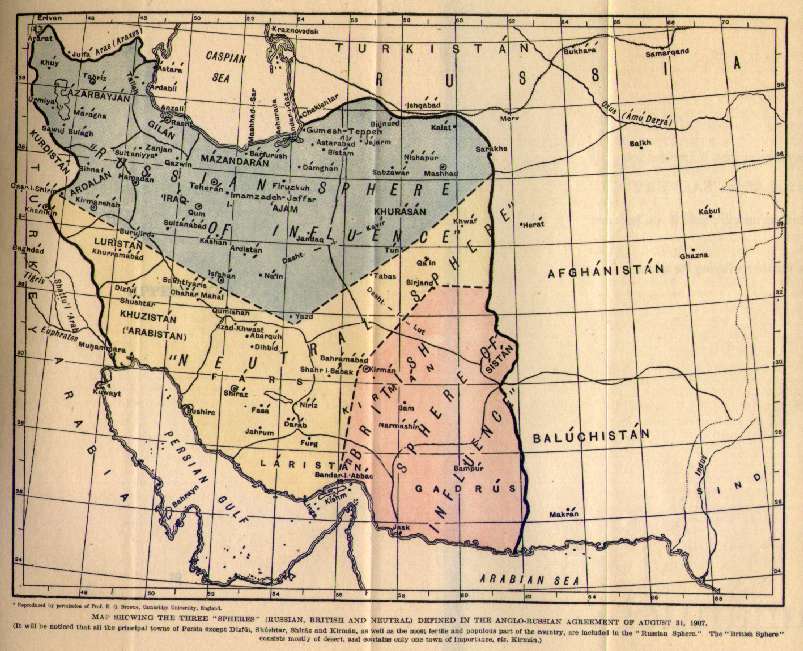

Growing his power and influence in the region, Khaz’al wanted assurances from the British government that he would be protected against outside threats. Whether it was the Russians or the central government. In June 1903 the British caved in and gave their word to Khaz’al that he would be protected against attempts against him. The relationship between Khaz’al and the British was so intertwined that Khuzestan or Arabistan wasn’t even mentioned in the 1907 Anglo-Russian agreement.

As you remember, the Anglo-Russian Convention divided Iran into two distinct spheres of influence. Russia dominated the northern regions, while Britain held sway in the southern territories. The central portion was designated as a neutral zone, reserved for the Persians themselves. But when it came to Khuzestan, both powers acted as if it was never part of the deal. They treated it as British territory, a protectorate under their control.

You should know that all of this was solely because of the Karun concessions. In 1907, other than its river and strategic placement, Khuzestan didn’t offer much value to the British. But another discovery in 1908 changed the game completely.

The Discovery of Oil in Khuzestan

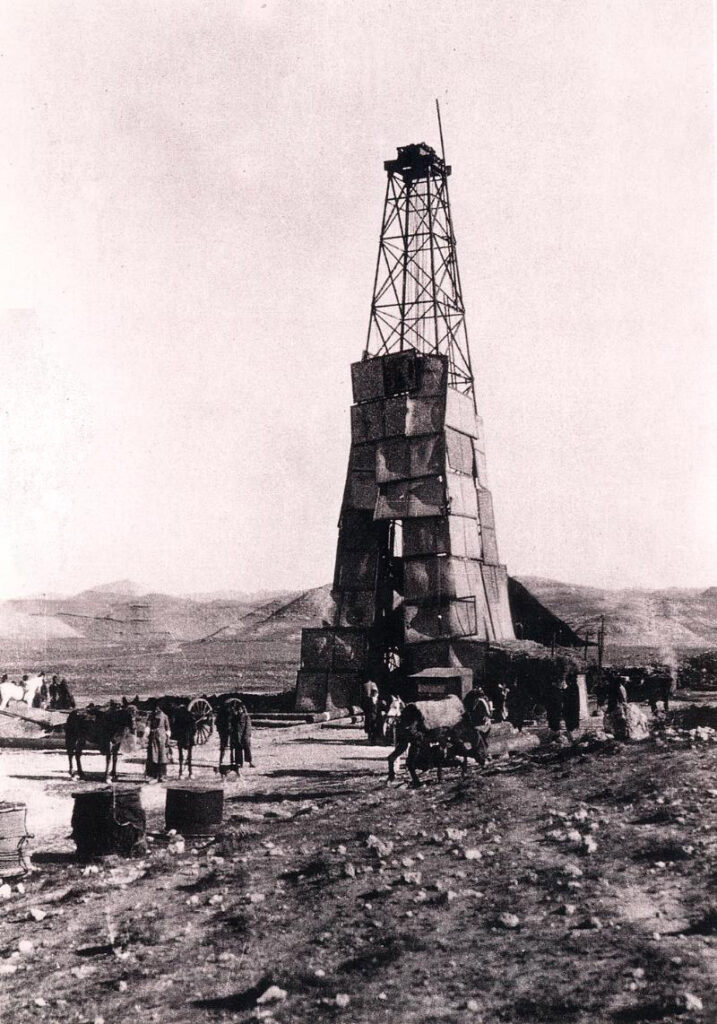

On May 26th, 1908 at roughly 4 in the morning, the British team tasked with scouting Khuzestan for oil fields was woken up to rambling shouts echoing across the land. As they got up and left their tents; they were met with a mountain of oil spurting above the derricks. It was the greatest oil field the British had ever found.

We talked about the discovery of oil in Persia in our eighth episode. William Knox D’Arcy, a British entrepreneur, was able to secure oil exploration rights in 1901 in one of Qajar’s concession purges. Despite harsh conditions and financial setbacks, D’Arcy’s team, led by George Reynolds, searched for seven years without success. But just as the backers decided to pull out, Reynolds struck oil in Masjid Soleiman on May 26, 1908. He uncovered one of the largest oil fields in British history and transformed the region’s future.

Fortunately for the British, Masjid-Soleiman was located in Arabistan, under the rule of Sheikh Khaz’al. This discovery turned Khuzestan from a minor protectorate within the Commonwealth into Britain’s most valuable strategic asset in the region.

Soon, the European superpower went into financial agreements with Khaz’al’s tribe for the protection of their drilling equipment and to guard their operations in the region. Sir Percy Cox who was the chief resident in the Persian gulf, even recommended more extrinsic incentives for the tribal leader to ensure his cooperation with the drilling. And thus, Khaz’al was even granted shares in the newly founded Anglo-Persian Oil Company.

But that wasn’t enough for the Sheikh.

A Knight of Persia: Khaz’al Receives Honors from the British

The Order of the Indian Empire was a British order of chivalry established by Queen Victoria on December 31, 1878. It was to honour British and Indian officials for their service to the British Empire in the region. The Order had three classes. CIE or Companion, KCIE or Knight Commander and finally GCIE or Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire. In 1917 through an elegant public ceremony, Sheikh Khaz’al received the title of Knight Grand Commander from the British Empire. He was now Sir Sheikh Khaz’al and was of the highest orders of the Indian Empire. After his knighthood, Khaz’al became a different person. This change of style was visible both in his personality and his appearance.

He was often seen wearing a military uniform adorned with numerous medals, bestowed by the British and Persian governments. The Persian central government no longer had any control over him. He refused to answer their letters or go to Tehran for official receptions. He was a king in his own land and felt no need to appease to a weak central government controlled by a dynasty that changed kings every few years.

Around this time, the British were also considering the official absorption of Arabistan into its territory.

The King That Never Was: Khaz’al’s Aspirations for Power

After World War I, the Ottoman Empire, was dismantled as a result of its defeat alongside the Central Powers. The empire was formally dissolved in 1920 and its vast territories was partitioned by the Allied Powers.

The region that is now modern-day Iraq was one of the territories affected by this dismantling. Previously known as the Ottoman provinces of Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul, the area was placed under British control. The British were granted a mandate over Iraq by the League of Nations in 1920. This allowed them to administer the territory and establish political order.

During this time, British wanted to absorb Khuzestan into Iraq. They were even considering appointing Sir Sheikh Khaz’al as its king. But the idea was soon dismissed and gave its place to the 1919 agreement.

The 1919 Agreement: How Iran – Almost – Became a British Protectorate

The Anglo-Persian Agreement of 1919 was a treaty proposed by Britain to increase its control over Persia’s financial and military systems. The agreement offered British advisors, military training, and a £2 million loan in exchange for significant economic privileges and influence over Persian affairs. It was widely seen as a move to turn the entire Persian empire into a British protectorate. An action that led to strong opposition from Iranian nationalists and its eventual dismissal.

Khaz’al who was looking forward to becoming king, was disappointed by this decision. The British, not wanting to muddy the waters with the Arab tribe leader, made a gift of 2,000 rifles, ammunition, four mountain guns and a river steamer to the sheikh hoping to win back his support. They also pushed Ahmad Shah to bestow the title of Sardar Aqdas to the sheikh. The title was part of the Imperial Order of the Aqdas. It was established by the Qajar dynasty to recognize loyalty and significant contributions to the state. It translates to “Most Sacred Commander” and was typically awarded to individuals who demonstrated exceptional service to the empire.

Although dismayed by the decision of the British to keep Arabistan in Persia, Sheikh Khaz’al couldn’t complain. He was at the height of his power. Revered by both the British and the Persians, he ruled Khuzestan like a king. He commanded an army, had ample ammunition and wealth, and enjoyed the backing of a global empire. Tehran had no sway over him, he paid no taxes on the customs duties he collected and ruled unchallenged.

There seemed to be no force that could undermine his authority.

That is … until a coup in the capital brought a soldier from the Cossack Brigade into the Persian political arena.

Reza Khan’s Rise to Power

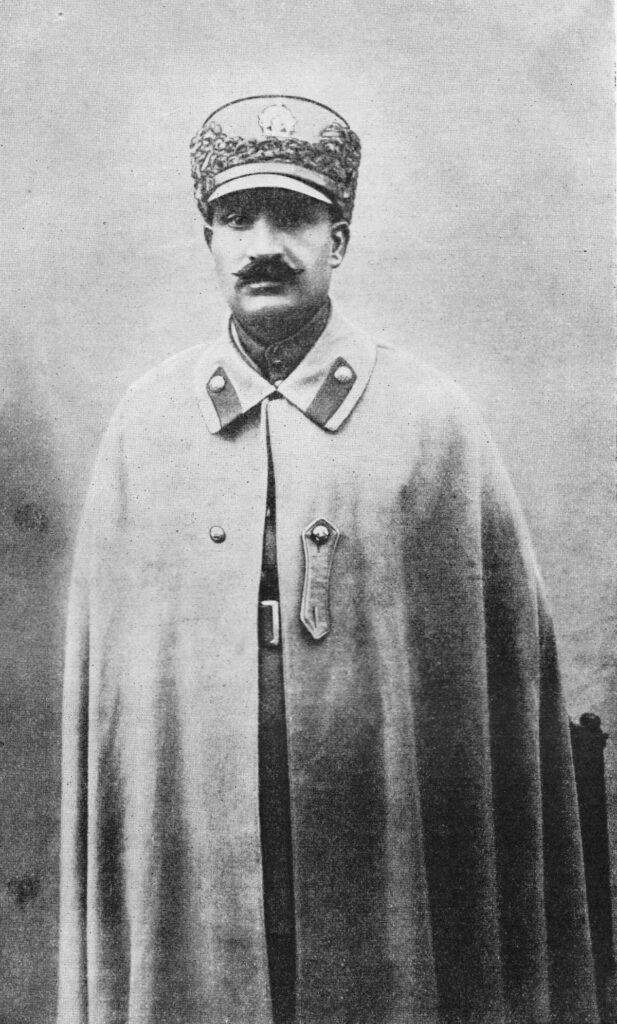

On February 21st, 1921, Reza Khan, who by then controlled a large fraction of the Cossack Brigade and was indirectly backed by the British, marched into Tehran. This military occupation forced Ahmad Shah to name Seyed Zia ed din Taba Taba ee as the prime minister. If you want to learn more about this story, we suggest listening to the ninth episode of this season.

The coup of 1921 resulted in the ousting of the prime minister. It also consolidated the power in the hands of the coup leaders. Seyyed Zia assumed the role of prime minister, while Reza Khan became commander of the army. Seyed Zia’s tenure as prime minister lasted only around three months. After Zia’s forced resignation, he was forced into exile. Reza Khan, on the other hand, grew his presence and soon became Iran’s prime minister.

Reza Khan believed in the power of the central government. He felt that tribal powers belonged to the history books. He saw them as nothing but an extra burden to Persia. These tribes didn’t pay taxes to the central government, most of their tribespeople were illiterate and due to their nomadic lifestyle, their workforce could not be utilized in Iran’s modernization and industrialization efforts. Even worse was the fact that after World War 1, most of these tribes had become pawns in the hands of the superpowers and only helped with their colonialist schemes. In the 1920s, 60% of Iran’s landscape was under the control of local tribes. Their independence from the central government posed a threat to Reza Khan’s vision of a unified nation.

Iran: An Ethnic Breakdown

In the north of Iran, the province of Gilan was governed by Kouchak Khan. Eastern Mazandaran and parts of northern Khorasan in the North-East were controlled by Turkoman tribes. In eastern and southern Khorasan, power was divided among roughly ten different tribes.

North-West province of Azerbaijan – along the Russian border – Eqbal al Saltaneh Makou ee held sway, while Semit’qu ruled the area from west of Urumieh to the Turkish border. To the West, areas around Kermanshah were governed by the Sanjabi and Kalhor tribes. Lurestan was under the rule of Lur tribesmen, and central and parts of western Iran were under the Bakhtiaris’ control.

In the south, Baluchestan were under the domain of the Baluchi tribes, with Baluchi chief Doost Mohammad Khan so influential that he even minted coins bearing his name. Finally, the province of Khuzestan or Arabistan was controlled by the Banu Ka’ab tribe led by Sheikh Khaz’al.

Reza Khan’s Vision for a Unified Iran

Ever since becoming minister of war, Reza Khan had tried to use the cossack brigade and the new centralized army of the capital to quash the rebellions of those tribes that opposed the government. Yet, none of these nomadic groups posed a bigger threat than Sheikh Khaz’al and his independent rule in the Khuzestan region.

Reza Khan knew that Sheikh Khaz’al’s total autonomy in one of the most important provinces posed a threat to Iran’s unification. Even if all other tribes were brought under control, the existence of Khaz’al and his free roaming in the region would allow others to follow suit and rebel against the capital. But Reza Khan had to be deliberate and calculating in his actions. Sheikh Khaz’al was strongly supported by the British. Tehran’s army was still not fully equipped. And most importantly … Reza Khan still didn’t have enough political capital to spend.

One year after the coup of 1921, the central government, in dire need of cash, decided to send a formal request to the sheikh to settle his account with the capital. Despite collecting the entire costume revenue from the port of Khoram shahr, Sheikh Khaz’al had paid no taxes since 1913 nor accounted for any customs receipts that he had collected. This was in part because Tehran’s government was too scared of his tribe and the British support of him to ever formally request payment.

The Clash Between Reza Khan and Sheikh Khaz’al

Upon receiving the request, the British consul in Ahwaz recommended him to reach a settlement with the Capital. But Sheikh, too proud and confident in his position, decided to ignore the request. Sheikh, a citizen of the country had rejected the orders of the centralized government. Now Reza Khan had official cause to act.

As Reza Khan was getting ready to face Khaz’al, the politics of the capital got a bit complicated. The Wheat shortage of 1922 led to Reza Khan’s temporary resignation and the drive for republicanism, which soured the relationship between the prime minister and the parliament. But this temporary setback was not going to dissuade Reza Khan from taking back Khuzestan from the hands of Khaz’al.

As Reza Khan was consolidating his power, he started the process of putting together his army once again. This time to march south and eradicate the threat of Khaz’al once and for all.

Read part two of this story here.

2 Responses