This is the transcript for Part Two of a special episode from The Lion and the Sun podcast: Arabistan. How Reza Khan amasses an army and faces Sheikh Khaz’al and his unchecked rule in Khuzestan.

Read part one here or listen to both episodes on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or all other podcast platforms.

Apologise or Die

These were the only choices left for the tribal leader of Khuzestan. The man who once ruled over Iran’s most influential province now faced the annihilation of his entire tribe.

Sheikh Khaz’al al-ka’bi had come to power in 1897, after assassinating his brother. His tribe controlled Khuzestan, a southwestern province known as Arabistan or “Land of the Arabs.”

After his ascension into power, Khaz’al had aligned himself with Britain, ignoring Tehran’s authority. His relationship with the British had deepened after the discovery of oil in Khuzestan in 1908, which made the province a strategic asset.

Only a few years before, he had received a knighthood from the British government and his land was considered an independent territory even by the Qajar kings. He answered to no one, paid no taxes and had the backing of international players. He had full autonomy and was free to do as he pleased.

But now … things were about to change.

An army of 15,000 troops, led by the prime minister himself—a man known for his ruthlessness—was on the march. Their mission: to bring Khaz’al to his knees and dismantle his rule once and for all.

Reza Khan, a soldier who had fought his way through the ranks to become prime minister, viewed tribal leaders as obstacles to his vision of modernization and national unity. This was especially true in Khuzestan, where Khaz’al had governed unchecked. To unite Persia, Reza Khan knew Khuzestan had to be brought under control.

As the capital’s army drew nearer, Sheikh Khaz’al sat in deep contemplation, facing his ultimate dilemma and weighing the options

Apologise or Die.

Aftermath of Reza Khan’s Republicanism

Reza Khan was a risk taker; but never without purpose. He knew the system, the players. and the board. Every move was thought through, and every decision weighed. That’s why the defeat of the republican movement hit him hard. It wasn’t just a loss, it shook his confidence and shattered the bigger dreams he held close.

In 1924, Reza Khan believed the time had come to break free from the constitutional monarchy and establish a republic. Like the neighbouring Turkey, he wanted to end the monarchy, declare a Republic of Iran, and become its first president. He thought after years of turmoil under the Qajars, Iran was ready to move beyond the old ways.

He was wrong.

The Majlis—Iran’s parliament—led by Hassan Modarres, overwhelmingly rejected Reza Khan’s proposal. They stood firm in support of the monarchy and the Qajar dynasty, which sank the prime minister’s vision for a republic. Reza Khan had no choice but to abandon the plan. But for Modarres, a staunch opponent of the prime minister, that wasn’t enough. Seeing Reza Khan’s weakened stance, he scheduled a vote of no confidence in the parliament to oust him for good.

Surviving the Vote of No-Confidence

As the day of the vote drew near, Reza Khan reshuffled his cabinet, signalling what many saw as an attempt to sway the Majlis against a vote of no confidence. The new lineup included respected figures from previous administrations—names favoured by monarchists and backed by the British. Even the son of Sardar As’ad, the constitutional leader who played a key role in the Battle of Tehran, was brought in. But these changes weren’t about winning votes … Reza Khan was preparing for war.

Before the vote of no confidence, Reza Khan already knew he had enough support to remain in power. Despite setbacks, many still saw him as a force for change and wanted him to continue as prime minister. The cabinet reshuffle wasn’t about saving his position. It was an excuse to prepare his government for a face-off he had been postponing for years!

Rouge Province: The Khuzestan Conundrum

Ever since the coup of 1921, Reza Khan had set his sights on Khuzestan. A semi-autonomous province ruled by Sheikh Khaz’al, the powerful leader of the Banu Ka’b tribe. For years, Khaz’al refused to pay taxes on the customs he collected at the border and ignored the central government’s authority. Reza Khan had formally asked Khaz’al to settle his debts, but the sheikh’s defiance had only fueled his grudge further.

For Reza, nothing mattered more than the unification of Iran. He believed the only way forward was through a strong, centralized government. In his eyes, Sheikh Khaz’al and his autonomous control over Khuzestan were the biggest obstacles standing in the way.

Khuzestan’s Power Struggle: Tribal Alliances and Resistance

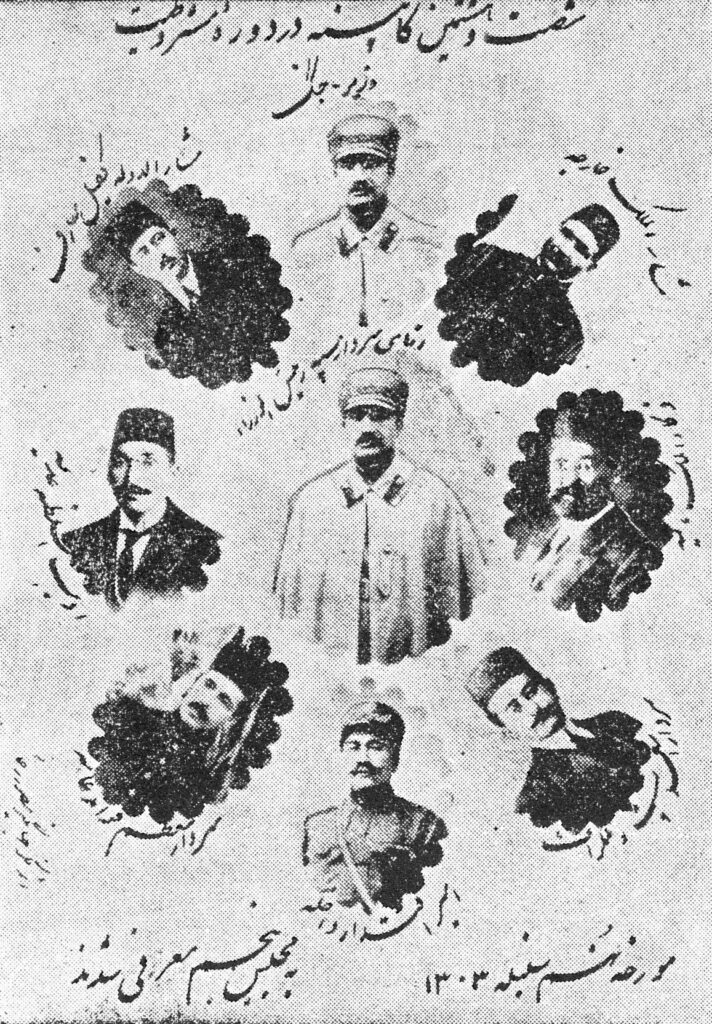

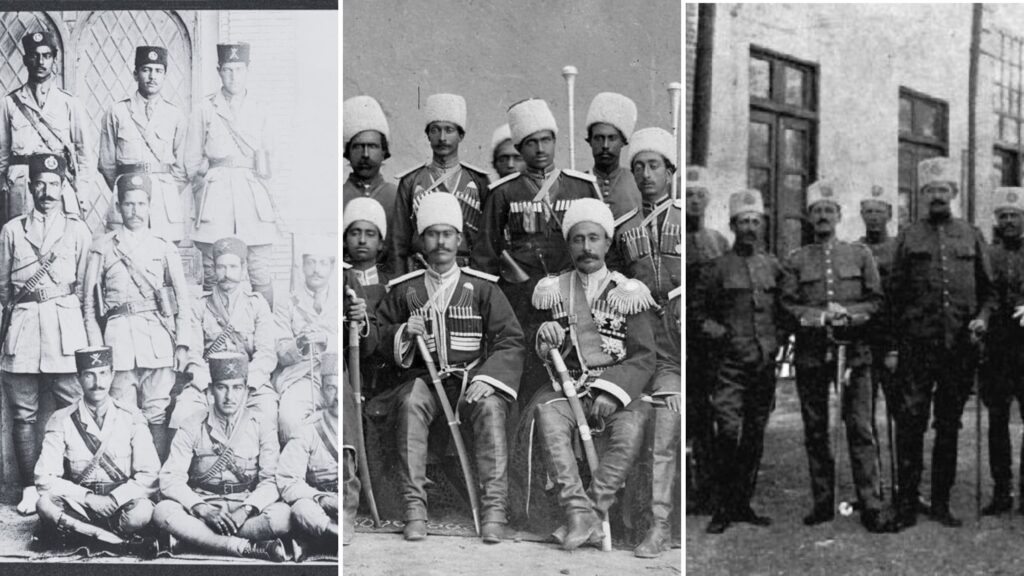

But in 1921, Reza Khan was not yet in a position to act on this impulse. Several obstacles stood in his way. The most significant being the absence of a unified military. At that time, Iran had three separate armed forces.

The South Persian Rifles, created by the British during World War I, secured southern provinces to protect British interests, particularly oil fields and trade routes. The Gendarmerie, formed with Swedish assistance, maintained order in rural areas and countered tribal unrest. The Cossack Brigade, led by Russian officers, was stationed in urban centers and wielded significant political influence.

After the fall of the Russian Empire, the British moved quickly to control the Cossack Brigade. But Reza Khan, with his military background and connections, managed to take command. Now, he was focused on merging the other two forces into a single, unified army.

Busy solidifying the army, consolidating power in the capital, and climbing the ranks, Reza Khan had to put the issue of Khuzestan on hold. He knew that a direct confrontation with Khaz’al could provoke the British and jeopardize his political survival. But he still couldn’t resist testing the waters.

Reza Khan Tests Khuzestan: Probing Khaz’al’s Defenses

In 1922, Reza Khan launched a probing operation against the Lurs and Bakhtiari tribes in the west. He sent a small unit of his army to the region. Officially, this operation was meant to look into reports of aggression caused by the local tribes. Its real aim however was to push into northern Khuzestan and gauge the reactions of both Khaz’al and the British. Reza Khan was assessing his options before making a move against Khaz’al.

During this time Khaz’al had also not been sitting idle. For the past year, he had been negotiating with Bakhtiaris, The Lurs and other smaller tribes to create a tribal alliance. The aggression in the north of Khuzestan was also his plan to see if Reza Khan would respond and take the bait.

In early 1923, Reza Khan saw the fractured tribes of the southwest as an opportunity. Like the Qajar kings before him, he exploited their divisions. He encouraged younger khans to challenge their elders and fueled rivalries among the groups. Each move was carefully calculated to weaken their hold and strengthen his own. Once the conflicts took root, he systematically disarmed the tribes, dismantling their power one by one.

Favours and Friendships: Reza Khan Shuffles His Cabinets

In July of 1924, as the day of the vote of no confidence drew near, Reza Khan reshuffled his cabinet, signalling what many saw as an attempt to sway the Majlis against a vote of no confidence. But these changes weren’t about winning votes.

For Reza, the obstacles in his path to taking back Arabistan went beyond Khaz’al and his army. Two other factors loomed large: British support for Khaz’al and Khaz’al’s alliance with the Bakhtiaris. The new appointments were a strategy to neutralize both threats.

The new cabinet featured respected figures from past administrations, favoured by monarchists and backed by the British. By appointing a pro-British cabinet, he aimed to keep relations steady with the foreign superpower. Choosing the son of Sardar As’ad as the minister of post and telegraph was no accident either. It was a clear signal of friendship with the Bakhtiaris.

By the August of 1924, Reza Khan’s army was ready. Thousands of men with armoured cars, observation planes and even bombing racks at their disposal.

He was ready to strike.

Tensions Rise: Khuzestan Prepares for War

Seeing time slipping away, Sheikh Khaz’al began preparing for war. He rallied his tribal forces and called on his Lur and Bakhtiari allies for support. He even informed the British Consul in Ahvaz that his men were on high alert, ready for whatever Reza Khan might send their way.

Khaz’al knew that Reza Khan had no love for Ahmad Shah. In fact, it was Reza Khan who had driven the king into self-exile in Paris. The king’s political capital and favourability had decreased in the last year, but he was still the king and swayed immense power. So, on September 14th, Khaz’al sent a telegram to the Qajar king. He personally invited him to return to Persia through Arabistan.

Two days later, Khaz’al wrote a separate note to the parliament, all foreign legation in the capital, and even the prominent clergies. He accused Reza Khan of overstepping his authority as prime minister and seizing the Shah’s powers. Khaz’al argued that Reza’s actions violated the constitution and undermined the democracy people had fought hard to establish. He assured the recipients that his tribe was doing everything it could to curb the prime minister’s power and bring the king back to Iran.

“He is an enemy of Islam, the Shah, and the constitution.” Khaz’al declared. “I will either overthrow Reza Khan or die trying.”

Khaz’al was leveraging both his military and political connections to deter Reza Khan from attacking his land. He was trying to create a shield of protection around himself in order to remain in power.

But Khaz’al was overestimating his influence.

Britain Withdraws: Khaz’al Stands Alone

After World War I, the British began to rethink their global strategy. With new mandates in Iraq and Palestine, they wanted to scale back their presence in Persia. They believed that a strong, centralized government in Tehran would ultimately protect their oil interests.

Although higher-ups at the Anglo-Persian Oil Company weren’t fond of Reza Khan, they knew that Khaz’al’s rhetoric was growing more hostile by the day. Even if Khaz’al won this conflict, there was no guarantee the next government wouldn’t turn against him.

But that wasn’t everything. On the national stage, Khaz’al was immensely unpopular. Years of sucking up to the British had turned him into the symbol of anti-nationalism. Even Reza Khan’s opponents didn’t have a favourable view of him. They saw him as a British agent trying to further fragment their country.

Sensing the shift in tides, Reza Khan decided to act. He wrote to the British Military Attaché that he could now mobilize 40,000 troops and march to Arabistan. This force, he assured them, was enough to crush Khaz’al’s troops and any other tribe that dared to oppose him. He warned that if any damage were to come to the oil installations in the process, Khaz’al would be solely to blame.

The British, knowing Reza Khan to be a man of his word, decide to backtrack their support of Khaz’al.

They argued that their protection of his tribe had always been conditional on his loyalty to the central government. By rebelling against Tehran and refusing to pay taxes, Khaz’al had violated this agreement. The British were no longer bound to defend him.

The Final Ultimatum: Khaz’al’s Last Chance

The British, in an attempt to de-escalate the situation, invited the sheikh to come to Tehran and settle his debt.

But Khaz’al refused.

In recent years, unchecked power had clouded Khaz’al’s judgment. A rule that began with kin slaying, had left him blind to reality. He had become arrogant, ruthless, and oblivious to the shifting tides unfolding before his eyes.

In October 1924, Reza Khan informed the British that he had made up his mind. He had completed the preparation and was now getting ready to lead 15,000 troops to Khuzestan. There was nothing the British could do.

“Apologise or Die.”

These were the options the British laid out for Khaz’al. They urged him to write an apology letter to Reza Khan, hoping it would halt the army’s advance and open the door for further negotiations.

Khaz’al was stunned by the British change of heart and their refusal to back him. But they weren’t his only problem. Reza Khan’s decision to include a Bakhtiary in his cabinet had worked. Many Bakhtiari tribes, once Khaz’al’s allies, were now refusing to support him out of respect for Jafar Qoli Khan.

Sheikh, now gripped by fear and uncertainty over his future, finally gave in. On November 14th, he penned a letter to Reza Khan, apologizing for his actions and pleading for forgiveness. The British, relieved by this gesture, thought the conflict could now be averted.

Reza Khan’s Advance and Britain’s Last-Ditch Diplomacy

Yet Reza Khan was done negotiating. The very next day, Reza telegraphed the British that he would accept Sheikh’s apology but he won’t stop his army. He argued that Iran’s winter was approaching fast and he would need to get his troops to a warmer region down south.

Sheikh Khaz’al had followed the British’s advice, yet the threat of war was growing closer with each passing day. One way out for him was to abandon Arabistan and seek refuge in Iraq. But the British dreaded this outcome. If Khaz’al fled his own territory—a region they had pledged to protect—it would undermine their credibility and weaken their standing with their allies. If they couldn’t secure a single province, how could the Commonwealth trust Britain to safeguard their interests?

To prevent the humiliation, the British requested a battalion of troops from India and three gunboats from Iraq to be stationed in Arabistan, hoping to stabilize the region and keep the situation under control.

Reza Khan had the superior army, but an extended clash wouldn’t have looked good for the aspiring prime minister. Especially when he had barely survived a previous crisis in the capital.

Leveraging their forces in the region, the British tried once again to ask for a meeting between the prime minister and Sheikh Khaz’al.

As Reza Khan’s army reached Shiraz, the British made another attempt to broker a meeting between the two sides. Reza Khan rejected the proposal. Meeting Khaz’al anywhere outside the capital, he believed, would diminish his leverage.

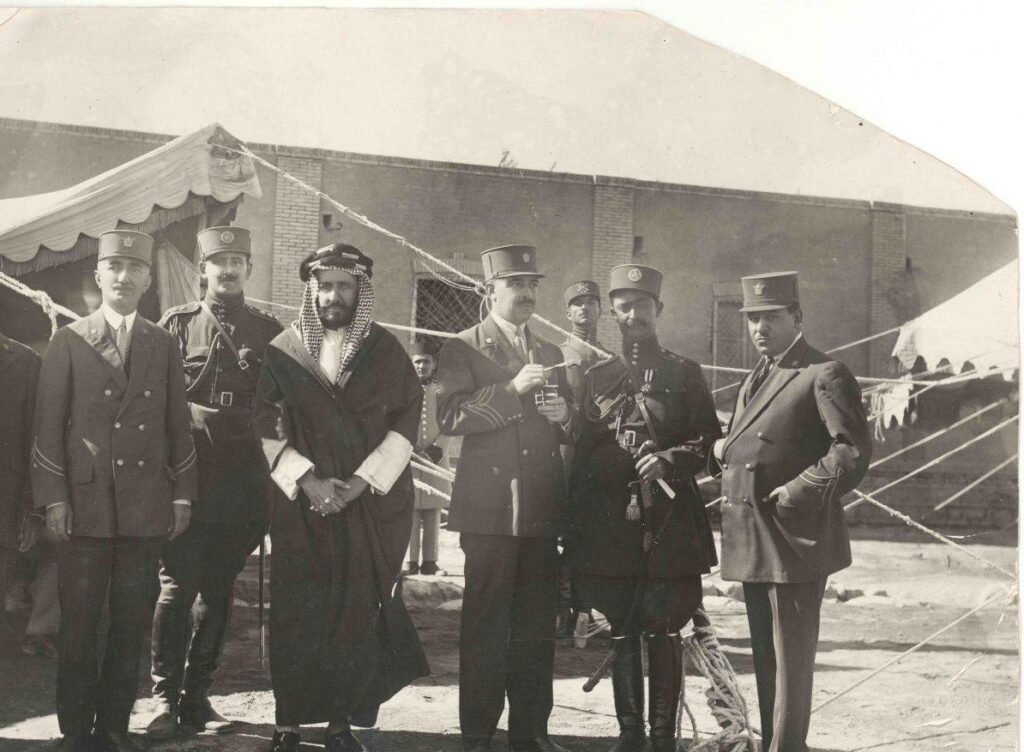

The Ahvaz Meeting: Reza Khan and Khaz’al’s Face Off

A few days later, Reza Khan arrived in Bushehr, the neighbouring province to Khuzestan. By then, he had reconsidered the meeting and put forward a counterproposal: he would agree to meet Khaz’al in Mohammareh or Ahwaz—two key cities of Khuzestan—but only if the sheikh travelled a considerable distance to greet him personally. His other condition was that the meeting would not be announced publicly.

The British who were running out of time and options, compelled Khaz’al to accept the proposal.

On November 27, Reza Khan and his leading column arrived at the border of Khuzestan. The rest of the army was still two weeks behind. This gave the prime minister and the sheikh a narrow window—two weeks to reach an agreement before the full clash.

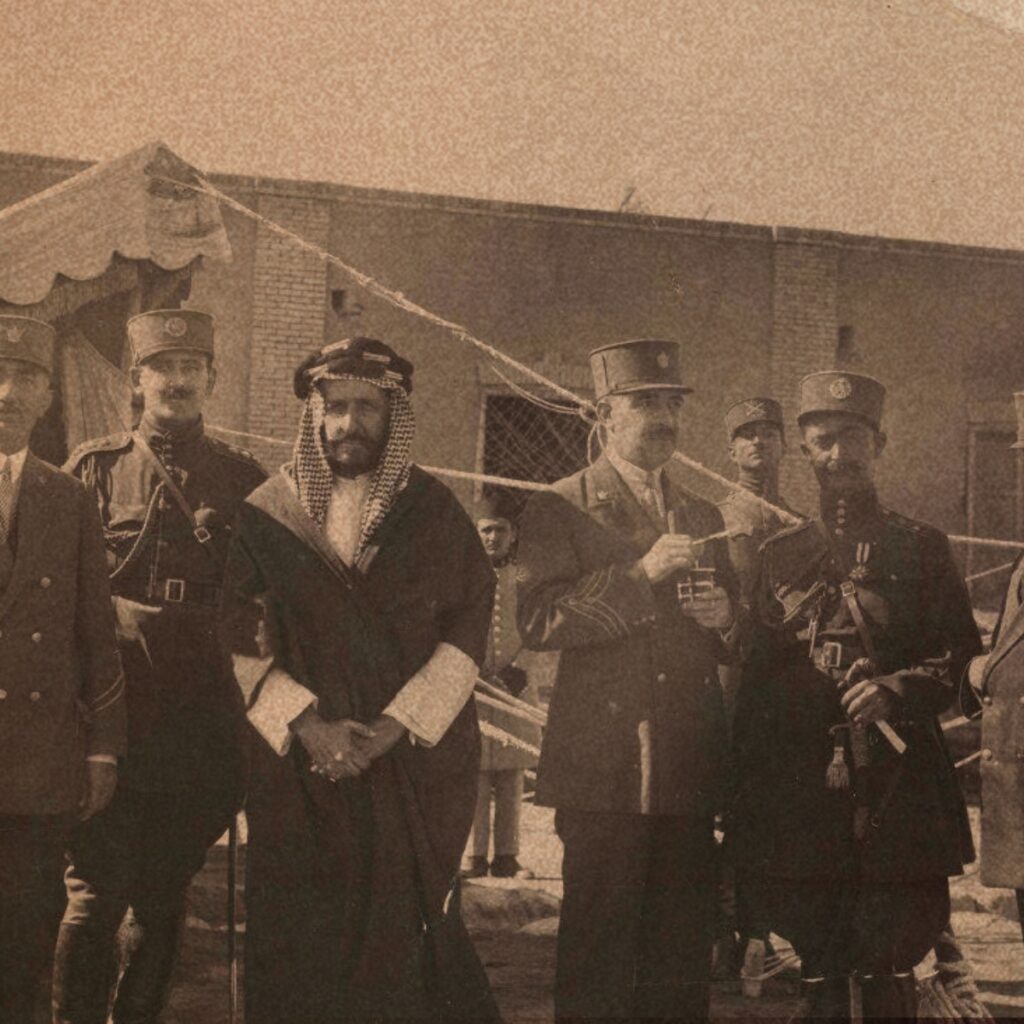

On December 6, Reza Khan and Sheikh Khaz’al finally met in Ahwaz. The meeting was tense and lengthy. For nearly a decade, these two powerful figures had been at each other’s throats, and now they had to find common ground.

Reza Khan didn’t want a full-scale war—especially one that could alienate the British. Khaz’al, on the other hand, knew he stood no chance against Reza Khan’s army and risked losing everything.

In the end, they reached an agreement: Khaz’al would keep his position and privileges as long as he recognized the authority of the central government and repaid what he owed to the capital. Reza Khan’s army would occupy the province until spring, and if all conditions were met, they would withdraw afterward.

Khuzestan Reclaimed: Khaz’al and Reza Khan’s Agreement

The deal was communicated to the British and they also approved. Soon, Reza Khan’s army had occupied the whole province. As a final resolution, Reza Khan revoked the name of Arabistan and restored the province to its ancient name …. Khuzestan.

Khuzestan was now firmly under the central government’s control, to be governed like the rest of the nation.

Before leaving Khuzestan, Reza Khan visited the oil fields for the first time and saw firsthand the empire the British had built for themselves. Though he was impressed, he couldn’t shake the resentment—resentment over how much control they wielded over Iran’s resources.

But there was little he could do about it. At least, not yet.

Afterward, Reza Khan made a pilgrimage to the holy Shia cities of Najaf and Karbala in Iraq. He then returned to the capital. On December 20, 1924, after months of conflict, Reza Khan officially pardoned Sheikh Khaz’al and signed documents affirming the sheikh’s ownership of his lands. He promised that Khaz’al’s family and descendants would not be harassed under his rule.

The bitter civil war between the capital and Khuzestan had finally come to an end. Or that’s what everyone thought.

Promises and Betrayals: The Arrest of Sheikh Khaz’al

Three months later, news came that Sheikh Khaz’al was planning to leave Iran and wanted to settle in Basrah, a city in Iraq. Citing that the issue of unpaid taxes hadn’t been fully resolved; Reza Khan invited Khaz’al to Tehran before his departure to settle his affairs.

After the agreement in Khuzestan, Khaz’al knew there was nothing left for him in Iran. Reza Khan may have granted him a pardon and access to his property, but the debt he owed the government was insurmountable. There was no way he could repay the unpaid taxes, and knowing Reza Khan, he wouldn’t rest until he collected every last qiran (Iran’s then-currency.)

Khaz’al was agitated by the invitation and decided to ignore the request.

In late April, as Khaz’al was preparing to leave, a group of soldiers stormed his boat and forcibly removed him and his eldest son. They dragged them out onto the street, where a car waited. The soldiers were acting under Reza Khan’s orders. An operation even the British knew nothing about. Their instructions were clear: take the sheikh to the capital.

Khaz’al’s Defeat: The End of Tribal Autonomy in Iran

Once in Tehran, Sheikh was sent to one of his properties and placed under military watch. The British who were taken aback by this new development wanted to see what had happened. But the only explanation that Reza Khan provided was that he had felt the sheikh’s residency in Khuzestan would have stirred more trouble.

The British tried to contact Sheikh Khaz’al in Tehran. They sent him a letter but the military forces of Reza Khan didn’t allow for it to be delivered. They tried to send a messenger to the residency but he was too denied entrance.

Frustrated, the British voiced their concerns to Reza Khan. The prime minister, known for his short temper, lashed out at the British attaché, making it clear that Khaz’al was an Iranian subject, and they would not be granted access without his express permission.

He further stated that the government had deemed Khaz’al a security risk, which overruled any personal connections or diplomatic courtesies. Unwilling to risk further escalation, the British dropped the matter.

Reza Khan’s Vision of a Unified Iran Realized

Ever since becoming the minister of war, Reza Khan had dreamed of a unified Iran. A country where the central government controlled everything and the whole nation would grow as one united entity. The existence of Arabistan and the rule of Sheikh Khaz’al had always undermined this dream. Reza Khan knew that even with an outward appearance of peace, Sheikh and his tribe would continue to cause trouble. So he had waited for the perfect opportunity to remove Khaz’al from the position of Power.

Isolated and confined to house arrest, sheikh Khaz’al continued his involuntary stay in Tehran. Despite the anonymity between the two, Reza Khan would often visit Khaz’al and would ask the soldiers to treat him with respect and dignity. Reza Khan knew Khaz’al was a threat, but at the same time, he respected his ambitions, his leadership and his grit.

In another world, they could’ve even been friends. But just like Khaz’al, Reza Khan didn’t believe in compromise. He only dealt with absolutes.

The Final Fate of Sheikh Khaz’al

Two years after Khaz’al’s forced move to the capital, the sheikh asked Reza Khan’s permission to go to Europe. He had an eye problem that was causing him to gradually lose his sight and go blind. Reza Khan rejected his request.

Reza never allowed Khaz’al to regain control over his tribe or his lands and barred Khaz’al’s family from accessing their father’s properties. In return, Khaz’al never paid his debt to the capital.

Two stubborn leaders, locked in a perpetual struggle for power, influence, and control.

Sheikh Khaz’al died on May 24, 1936. His imprisonment marked the final step in Reza Khan’s vision of a unified Iran, helping him solidify his authority and regain public favour. When Reza Khan returned to the capital in January 1925, he did so triumphantly, like a Roman emperor, except his victory had been achieved without shedding a drop of blood.

Had Khaz’al stayed in power, the issue of Arabistan could have escalated further. The British might have pushed for the province’s independence through the League of Nations, severing Iran’s hold over the vast southern oil fields with little resistance on the global stage.

By removing the sheikh, Reza Khan preserved the country’s unity and regained control of Khuzestan. This control over the province set the stage for a future confrontation between Reza Khan and the global superpower. This time not as a prime minister, but as a king.

A story that we’ll get to in the second season of The Lion and the Sun.

One Response