Watch the full video here:

The Qajar dynasty’s strategy was delegation, always shifting responsibility away from themselves.

To control the country, they handed over vast regions to tribal leaders in exchange for hefty taxes. Foreign relations were delegated to the nobility and a sprawling network of princes. As for national resources, these were sold to the highest bidder.

They sought power without the burdens of governance, craving only wealth and the illusion of control.

Under their rule, Iran suffered. The country’s borders shrank, distant regions operated as semi-autonomous states, and its resources were ruthlessly exploited. Mostly by the two neighbouring superpowers.

The Russian Empire in the north and the British in the south.

Disillusioned by their leaders, the people craved change. The first instance of this was the Tobacco protests.

From Tobacco to Majlis: The Persian Awakening

When Nasir Al-din Shah, the fourth king in the Qajar dynasty sold the Iranian tobacco industry to a British company in 1890, people became angry. After a religious fatwa, people stopped using tobacco altogether. Soon the government had no choice but to take back the concessions. The Iranians had finally found their voice and they were only getting started.

The assassination of Nasir al-Din Shah in 1896 set the stage for further turmoil. His successor, Mozaffar al-Din Shah, was ill-prepared to handle a nation on the verge of rebellion. After public outrage over the punishment of sugar merchants in 1905, people demanded a bigger role in politics. By 1906, persistent protests forced the Shah to establish the Majlis, Iran’s first parliament in 1906, ushering in constitutional governance.

From Bombardment to Civil Wars: The Chaos Years

But Mozaffar al-Din Shah was gravely ill, and soon after signing the constitutional order, he passed away. His son, Mohammad Ali Shah, wasted no time in dismantling these reforms. Backed by Russia, he bombarded the Majlis in 1908 and shut it down, triggering outrage across the country.

Protests erupted nationwide. In Tabriz, Sattar Khan and Bagher Khan led the resistance, while regional movements like Mirza Kuchak Khan’s Jangal rebellion in Gilan gained momentum. By 1909, resistance forces from the north and south had united, forming an army that marched toward Tehran.

Battle of Tehran and Its Aftermath

In July of that year, these forces captured the capital, forcing Mohammad Ali Shah to abdicate. Ahmad Shah, his young son, became king, and the second parliament convened, breathing new life into the constitutional movement.

While the Russian Empire was busy playing politics in Tehran, the southern superpower had its eyes fixed on its most prized asset: oil.

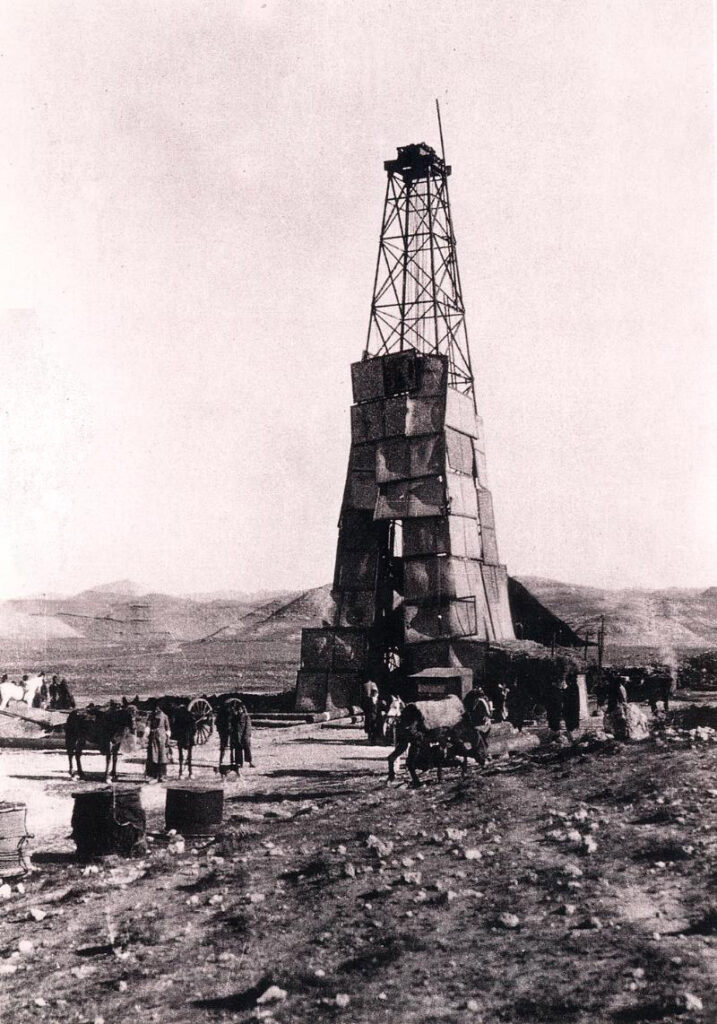

The discovery of oil in Masjid Soleiman in 1908 turned Iran into a strategic region for the British and impacted their role in the South. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company reaped the benefits while ordinary Iranians saw little improvement. Meanwhile, World War I exacerbated Iran’s fragility, with the country becoming a battleground for British, Russian, German and Ottoman interests.

In the aftermath of the war, Iran lay in ruins. The decade-long experiment with democracy appeared to have failed. Famine, destruction, and economic collapse left most people worse off than before. Disillusioned and desperate, they yearned for change—anything that might improve their lives.

Rise of Reza Khan

For many, that change came in the form of Reza Khan.

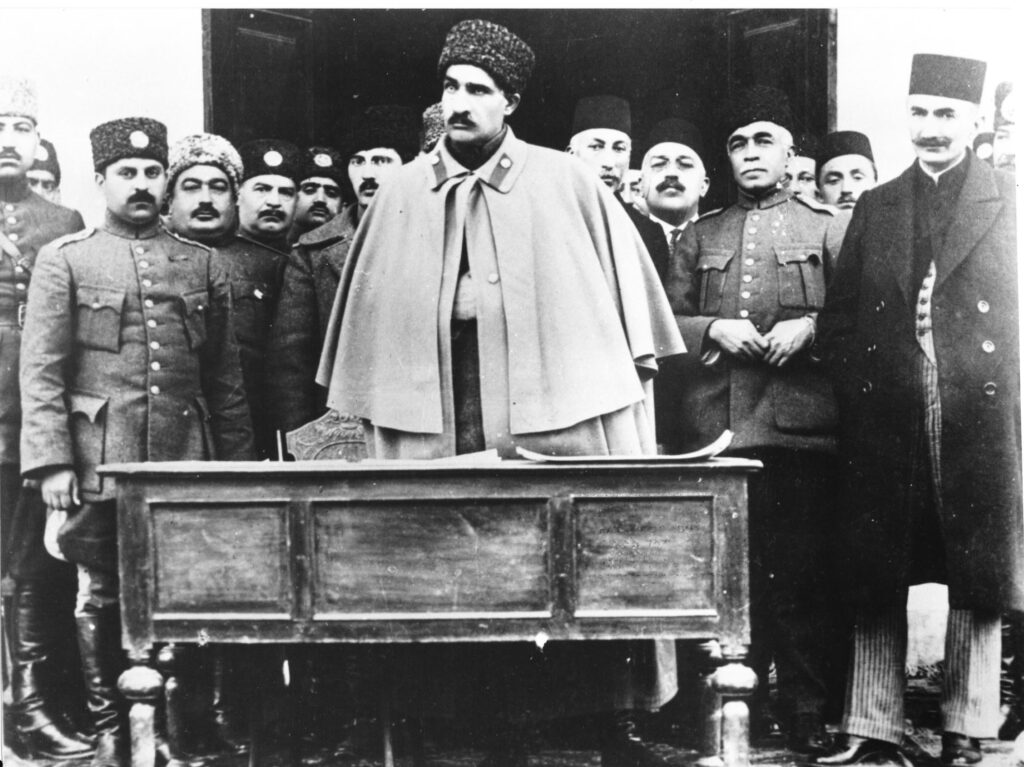

Reza Khan rose from humble beginnings to become a dominant figure in Iran’s modern history. Following the 1921 coup, Reza khan became the Minister of War, where he unified the army, subdued rogue tribal leaders, and eventually became the country’s prime minister. In a nation deeply divided by internal strife, Reza Khan imposed order and sought to build a cohesive state.

He despised the Qajar dynasty’s mismanagement and envisioned a unified, modern Iran capable of prosperity. He envisioned transforming Iran into a republic, with himself as the country’s first president.

But Iran wasn’t ready for a republic.

Prominent political figures, like Mohammad Mosaddegh, opposed the move, fearing that Reza Khan’s republic would devolve into a military dictatorship. Religious leaders, led by Hassan Modarres, resisted as well, suspecting it would lead to secularization akin to Atatürk’s reforms in Turkey.

Faced with widespread public backlash, Reza Khan’s proposal to establish a republic was defeated in March 1924.

But Reza Khan wasn’t ready to accept defeat just yet. If the nation wouldn’t accept him as president, he would declare himself the new king, establishing a new dynasty in his name and ushering in a new era for the country he had worked so hard to steer back on track.

In book two of The Lion and the Sun, we talk about Reza Khan’s new monarchy and his reign as Iran’s new king. Listen to the new season on January 29th.

You can listen to season one here or on all podcast platforms.

Follow us on Instagram, TikTok or X (Twitter).

For early access to episodes, become a supporter on Patreon.

2 Responses